By Jim O’Neal

On the east wall of the president’s office in the White House in 1845 hung a large map of the North American continent. Either Andrew Jackson or Martin Van Buren had acquired it and the geographical details were as accurate as science at the time could provide. This imposing map greeted James K. Polk when he entered the office as the newly elected president.

The map was printed in paper sections and glued to a linen backing. The eastern half showed the United States, with bold letters indicating ports, state capitals, large towns and turnpikes of the era. It was basically archaic, absent the new railroads and fast steamboat routes to the commercial hubs in New York, Pittsburg and New Orleans. However, the western half remained true to life, representing a vast land that lay wild and generally unused. For 300 years, Spanish landlords had largely left it undisturbed.

Now the Americans wanted it.

Their lust to possess was so strong and so emotional that it had the fervor of a religious awakening. With new territory, the republic would be free to expand, perpetuating Thomas Jefferson’s dream of a nation of farmers, counterbalancing the business and industry interests that dominated the urban East. In effect, it held the solution to saving the common man from the growing squalor of large, overcrowded cities. American expansion had not been a priority during Jackson’s tenure in office. In Polk’s, it was paramount.

The arrival of the Polks in Washington, D.C., in mid-February was greeted with more curiosity than enthusiasm. Polk was not well known as a public figure and everyone wanted to see the “dark horse” that had speared the presidency. He was only 49, the youngest president yet. Wife Sarah was a devout Presbyterian and loyal follower of the evangelical movement sweeping the United States. They quickly became viewed as partners in policy and politics, with strong views on important issues.

President Polk detested the idea of a National Bank, loathed the concept of big government and proved decidedly Southern, styling himself a true Jeffersonian. He expressed this comparison by moving David d’Anger’s bronze image of Thomas Jefferson from the Capitol to the White House lawn north portico, atop a pedestal of stucco brick. It remained there for 27 years, the only monument to a president ever to stand within the immediate enclosure of the White House.

However, the 1844 election had been about one grand issue: territorial expansion, with Mexico the obvious target. Manifest Destiny, a phrase popularized by Democrats to describe the sincere belief that the United States was divinely driven to rule from sea to sea, swept the nation. President Polk wholeheartedly endorsed the concept and as the annexation of Texas poisoned Mexican-American relations, the border between the two countries remained in dispute.

The United States claimed the Rio Grande as its southwest boundary and Mexico fixed it at the Nueces River. Polk dispatched John Slidell to Mexico to offer compensation for acceptance of the Rio Grande boundary, as well as an offer to purchase New Mexico and California. When this failed, Polk prepared for war by ordering General Zachary Taylor to bivouac 3,500 men in Texas. The Mexican Minister called the State Department for his passport and sailed home, severing diplomatic ties between the two countries.

The war arrived almost as if it was on a fixed schedule.

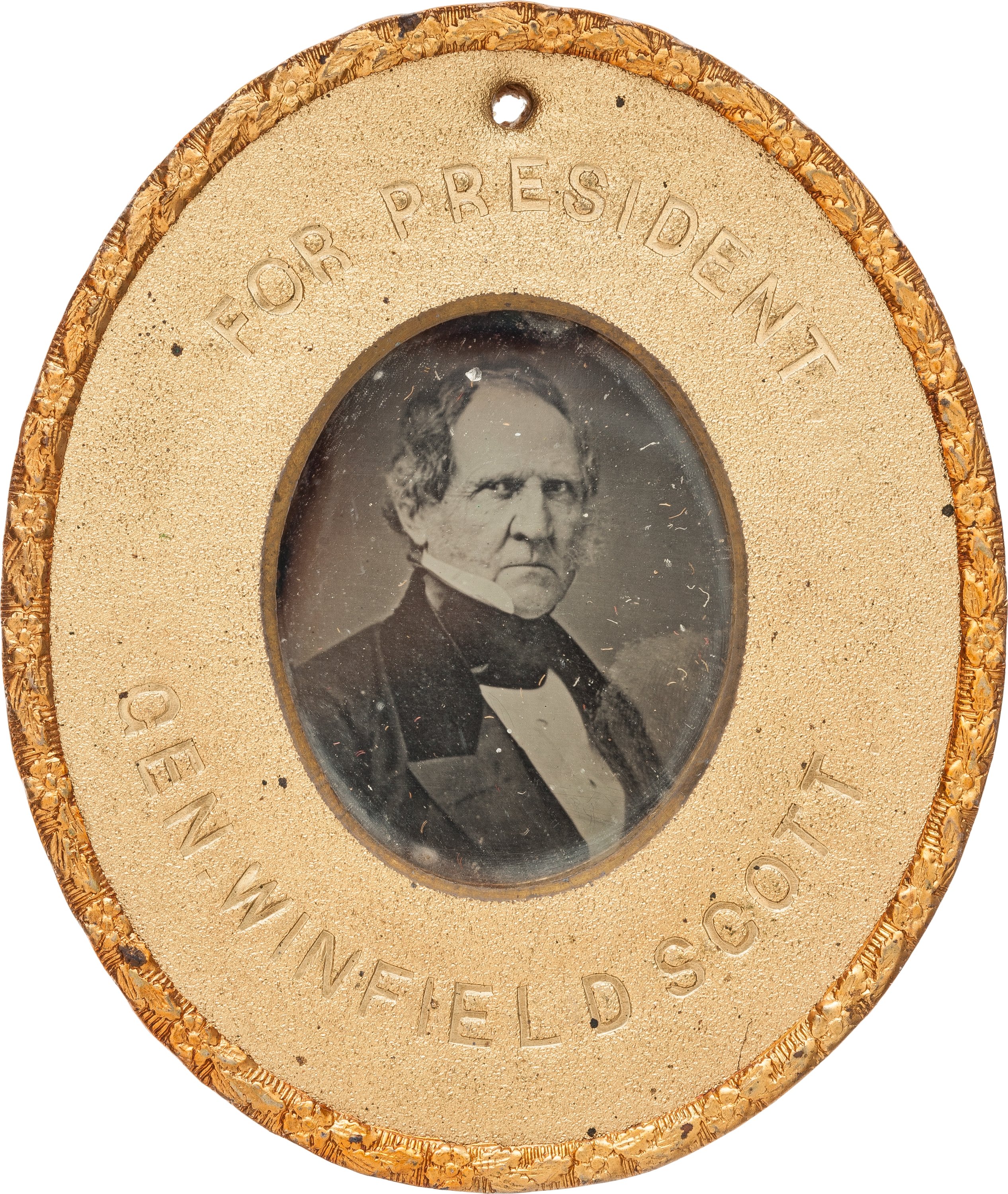

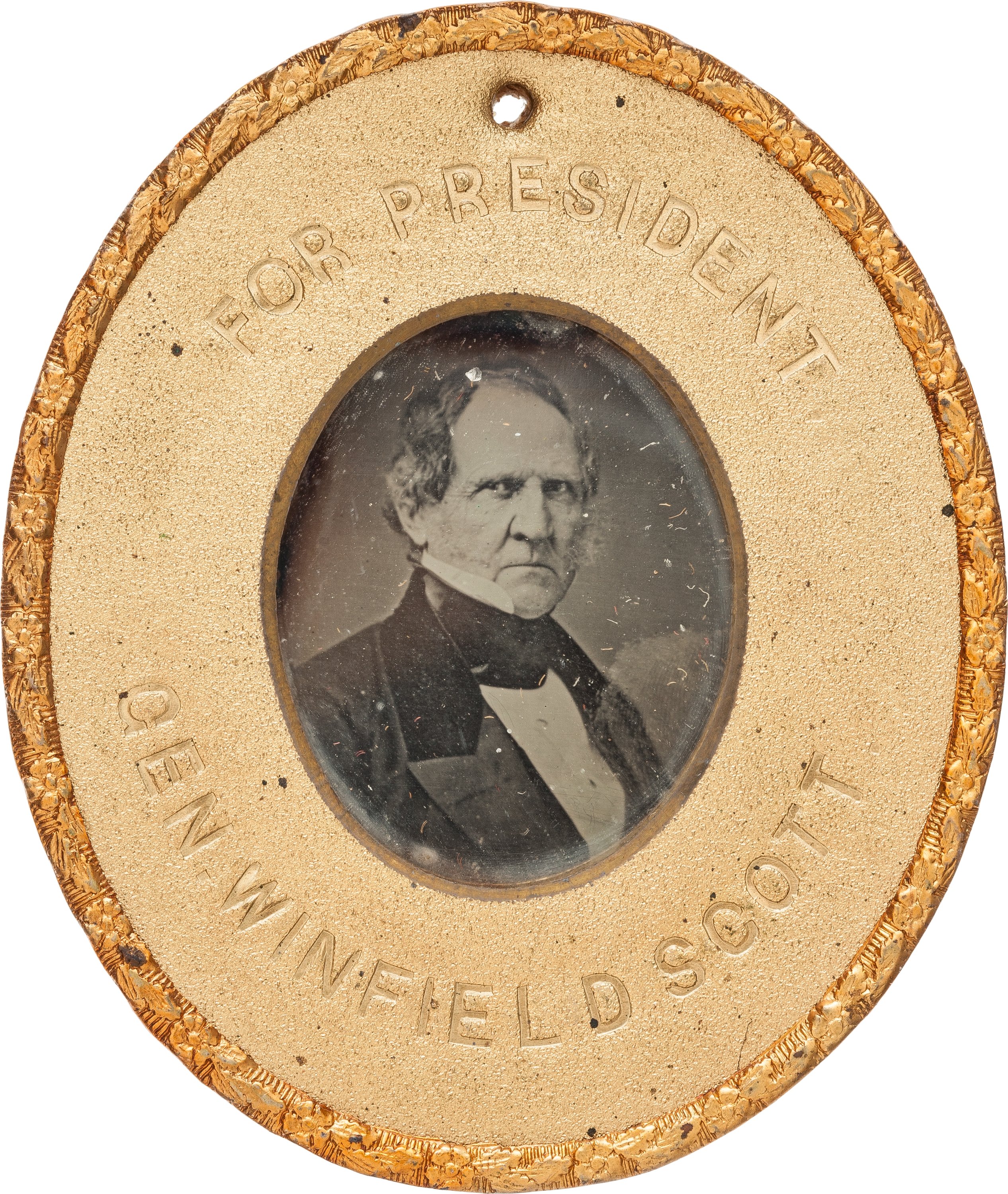

In April 1846, Mexican troops engaged Taylor’s forces in the disputed territory, thus providing Polk a concrete act of aggression on which to base his request for a Congressional declaration of war. On May 11, Polk charged “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon American soil.” Congress declared war two days later and General Taylor pressed south, defeating the enemy at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma and then capturing Monterrey. Then General Winfield Scott took Vera Cruz and occupied Mexico City. In January 1847, California fell into American hands, leading to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the end of the war.

The border was fixed at the Rio Grande and Mexico relinquished all or parts of modern California, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. The United States acquired more than 500,000 square miles, the largest single annexation since the Louisiana Purchase. Mexico was reduced to half its former size.

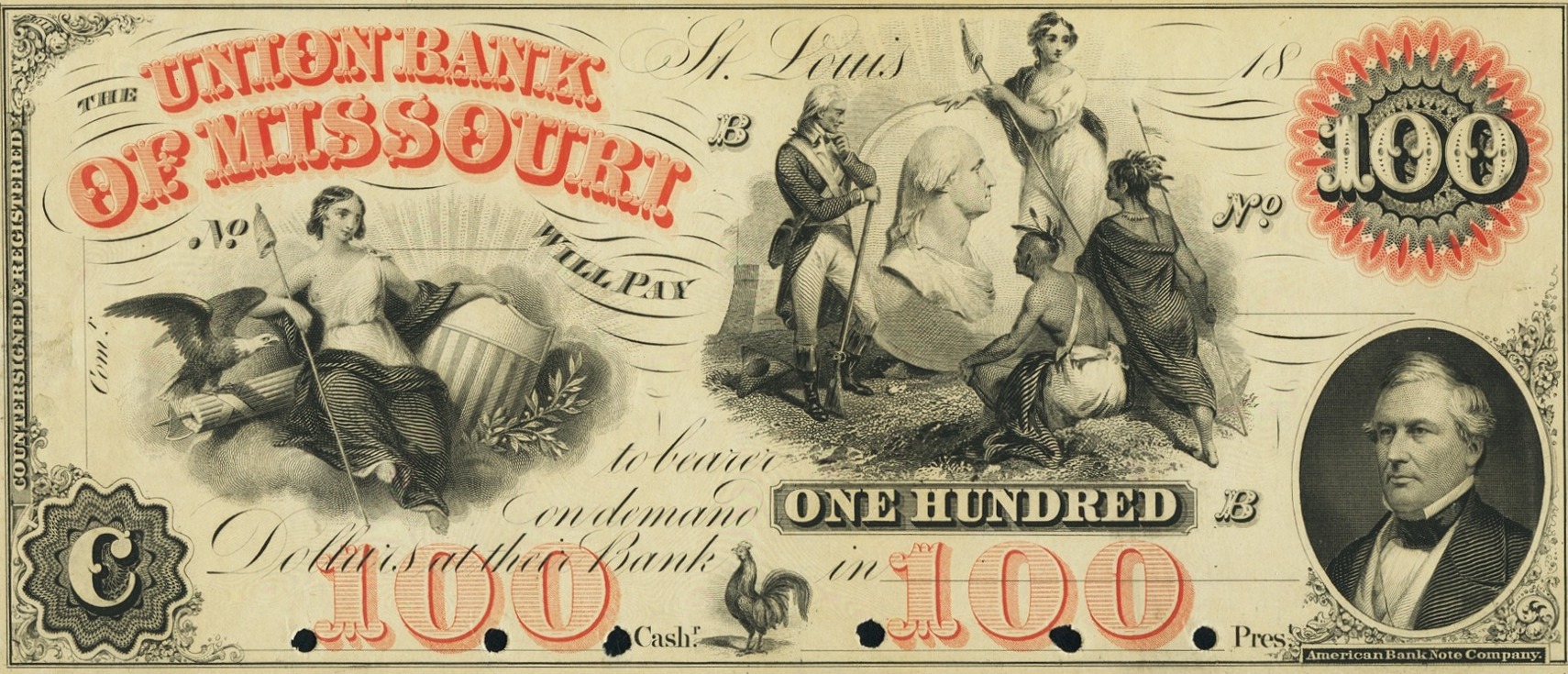

Inevitably, the discussion then quickly switched to the issue of whether to allow slavery in the newly acquired territory, a debate that would linger long after President Polk retired after his four-year term of office, as promised before his election. There are no records I can find regarding the fate of that aspirational map that was hanging in his office when he arrived. It would have required significant revisions to reflect all the changes that occurred in four short years.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].