By Jim O’Neal

Cosmologists generally agree the universe is 13.8 billion years old, and Earth 4.6 billion years old. They also agree the universe is expanding at an ever-increasing rate, and is creating new space in the process. It is already so immense that even by traveling at the speed of light, you would simply end up back where you started due to the curvature of space. This eliminates one of my lifelong desires to poke my head thru and “see what’s out there.” The answer is nothing, a hard concept to grasp … at least for me.

What no one seems to know is where, when or how life on Earth began. Or, for that matter, if life (as we know it) exists anywhere other than on our small tiny orb tucked in a remote part of our modest galaxy, at the precise distance from the Sun to permit our existence.

Author Bill Bryson writes about the work of a graduate student at the University of Chicago, Stanley Miller, who in 1953 tried to synthesize life in a chemistry lab. He hooked up two flasks, one containing water and the other a mixture of methane, ammonia and hydrogen gases. By adding electrical sparks to simulate atmospheric lightning, he was able to convert this concoction to a green and yellow broth of amino acids, fatty acids and other organic compounds. His euphoric professor – Nobel laureate Harold Urey – exclaimed, “If God didn’t do it this way, he missed a good bet!” Since it was subsequently pointed out that Earth never had such noxious conditions, we are no closer to creating life today, 65 years later.

Others have speculated that life on Earth arrived when a meteorite crashed into the planet in a process known as panspermia. The problem with this theory is that it still doesn’t explain how life BEGAN and just moves the problem to some other remote place.

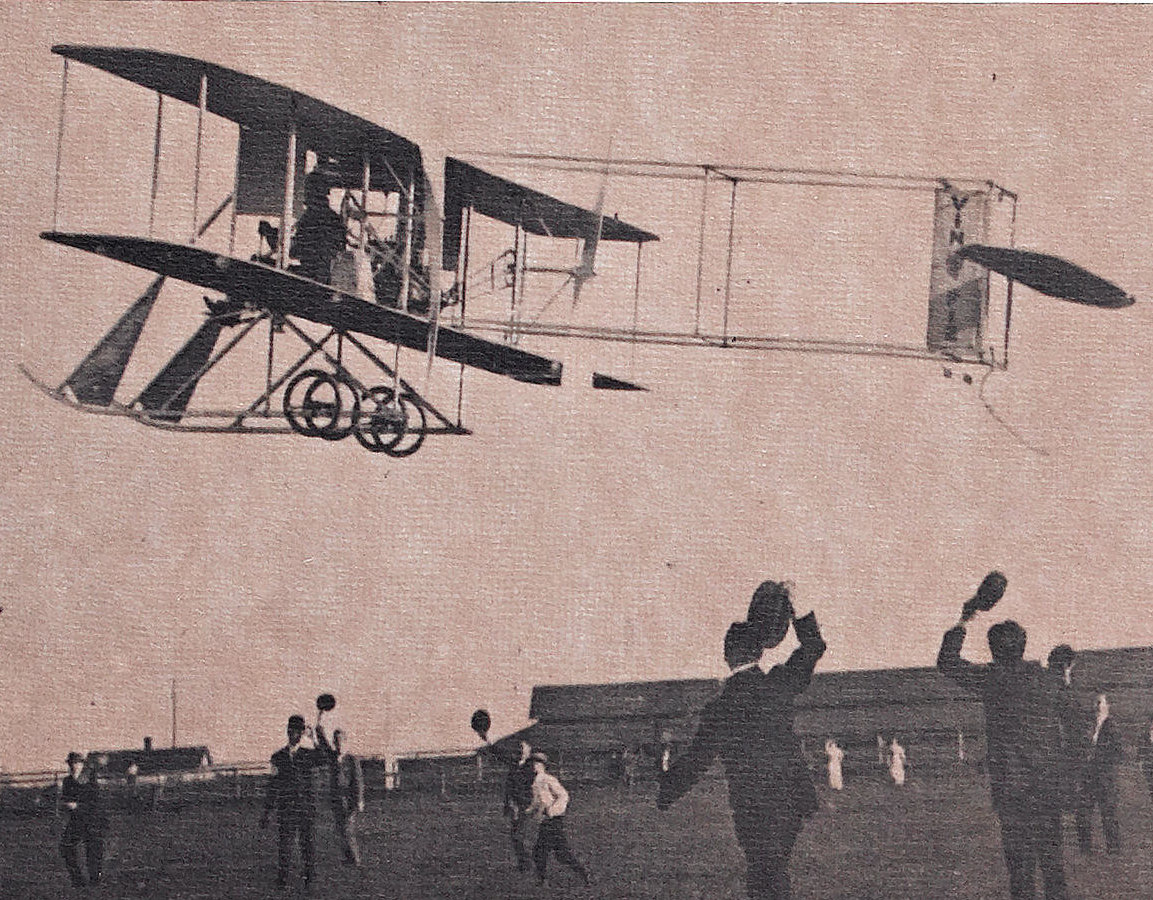

Since modern man dates back 200,000 years to Africa, I’m more curious as to why it took us so long to fly. It was only rather recently, on Dec. 17, 1903, that two brothers from Dayton, Ohio – Orville and Wilbur Wright – rose into the air in Kitty Hawk, N.C., and descended 120 feet further than the take-off point. Wilbur had tried first and stalled, but Orville took the controls and set off into a strong wind with Wilbur steadying the wingtip running alongside.

They made three more flights that morning, with the longest covering 852 feet. When a wind gust broke the airframe, they just packed all the parts and went back to Dayton. What makes this achievement even more remarkable is that neither had any formal academic education in physics, although both were high school graduates. Today, the “Flyer” hangs proudly above the entrance at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington under a long inscription that ends “…Taught Men to Fly and Opened the Era of Aviation.”

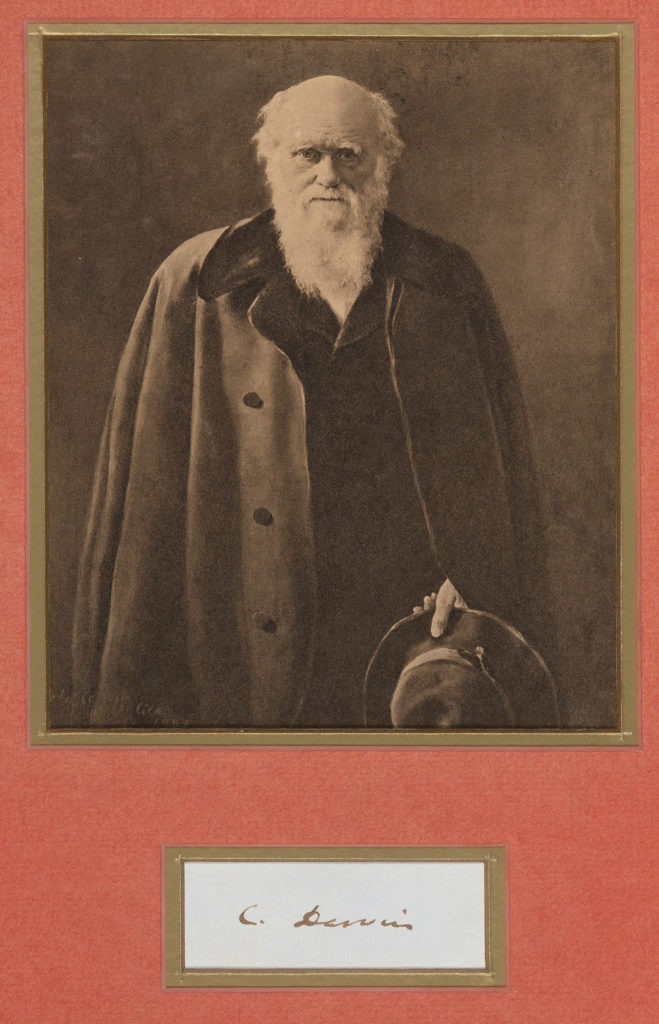

Of course, flying in the true sense has mostly been restricted to birds, as Charles Darwin theorized. In his travels aboard the Beagle survey ship, he noted that finch beaks on different islands in the Galapagos varied to exploit local resources. He speculated the birds had not been originally created this way, but had adapted themselves to gain a strategic advantage to acquire scarce resources. They had indeed, but it should be noted that Darwin did not coin the phrase “survival of the fittest” and even the word “evolution” didn’t appear until the sixth printing of On the Origin of Species. And even this book was delayed for many years since his editor urged him to write about pigeons. “Everyone is interested in pigeons.”

A lot has been written about “locomotion,” with the flight of birds being the most interesting … and the Pterosaur from 100 million years ago especially so. With a wingspan of 16 feet and weighing a mere 22 pounds, it was able to dominate eastern England by staying aloft for extended periods on rising warm-air currents … presumably as a hovering predator.

Once again, we face the same questions. How it developed is a mystery, as is its anatomy, since it couldn’t manage take-off via traditional wing flapping. Perhaps it relied on gravity and thermals to become airborne. But this would have required plunging into the air from seaside cliffs, like modern frigate birds.

My theory to cover all these mysterious questions is more simplistic: Evolution is just “one damned thing after another.”

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].