By Jim O’Neal

On May 10, 1865, President Andrew Johnson announced that armed resistance to the federal government had officially ended. However, on May 12-13 in the Battle of Palmito Ranch, a modest force of several hundred Union cavalry attacked a Confederate outpost on the banks of the Rio Grande, 12 miles from Brownsville, Texas.

Confederate troops had done nothing to break an unofficial truce with the Union forces, but after two days of fighting, they forced Union soldiers to first withdraw and then retreat. The skirmish is generally recognized as the final battle of the Civil War.

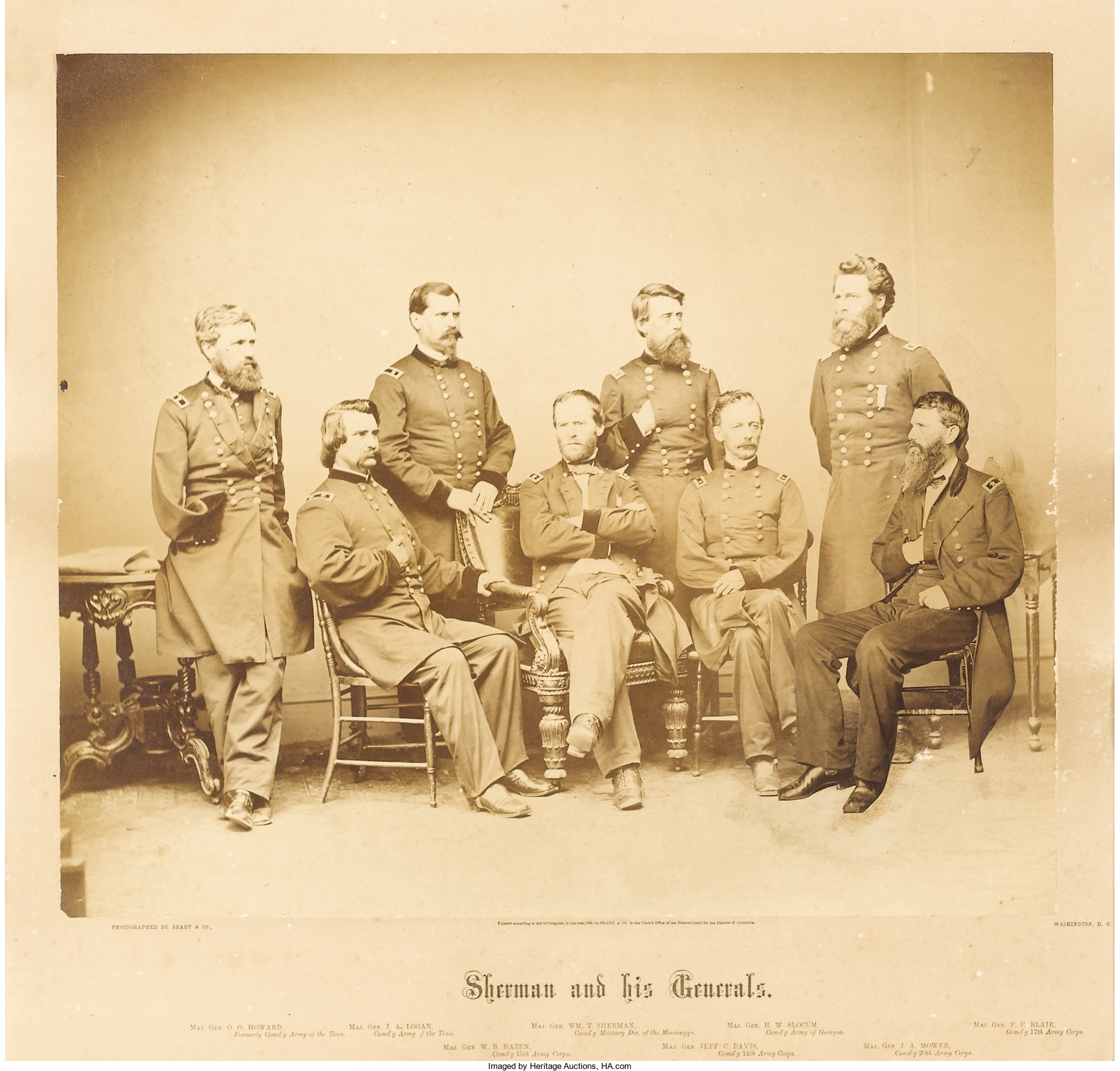

Before all the Union Army went home, there was a Grand Review in Washington on May 23-24 when Johnson and General Ulysses S. Grant watched the march of the triumphant Union armies down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol. This great procession of 150,000 men would take two full days, while thousands hoisted flags, hummed patriotic songs and showered the troops with flowers. Here was the titanic armada of the United States, the mightiest concentration of power in history. The first day was dominated by the Army of the Potomac, Washington’s own army. At 9 sharp the next day, General William Tecumseh Sherman’s great army took its turn. They were sunburned and shaggy in stark contrast to the crisp and well-kept group from the previous day.

The demobilization was completed very effectively. Within two months, more than 600,000 troops had been discharged and a year later, the million-man army was down to a mere 65,000 men. Further, the number of warships was reduced from 500 to 117 by the end of 1865. Thus, the armed forces did not remain a permanent power and the mustered-out military readjusted to civilian life quite easily. This was much different from those returning from World War II or Vietnam, or the 3 to 4 million still rotating from Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria (some on their fifth and sixth deployments in this l-o-n-g war).

Still, life after the Civil War was profoundly different. Aside from the human carnage and dismal impoverishment of the South, the centralization of the government changed the fabric of society. Until 1861, the only direct contact with the federal government was usually the postal service. Now, the War Department controlled state militias, direct taxes were imposed, national banking instituted, and federal money printed or minted.

The most radical change was naturally in the South. All seceded states were under martial law, an occupation force maintained law and order, and 4 million blacks were neither slaves nor citizens. The North imposed no organized vengeance; no Confederates were tried for treason – the only Southern war criminal was Henry Wirz, commander of the prisoner-of-war camp near Andersonville, Georgia, who was hanged in November 1865. And a military court dispensed swift justice to the Abraham Lincoln assassination conspirators, with four hanged at the Old Penitentiary on July 7.

However, reconstruction of the pre-war Union of the United States was under way and Lincoln’s most fervent prayer – reunification – finally a reality despite the horrendous loss of life involved. Peace had been restored.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].