By Jim O’Neal

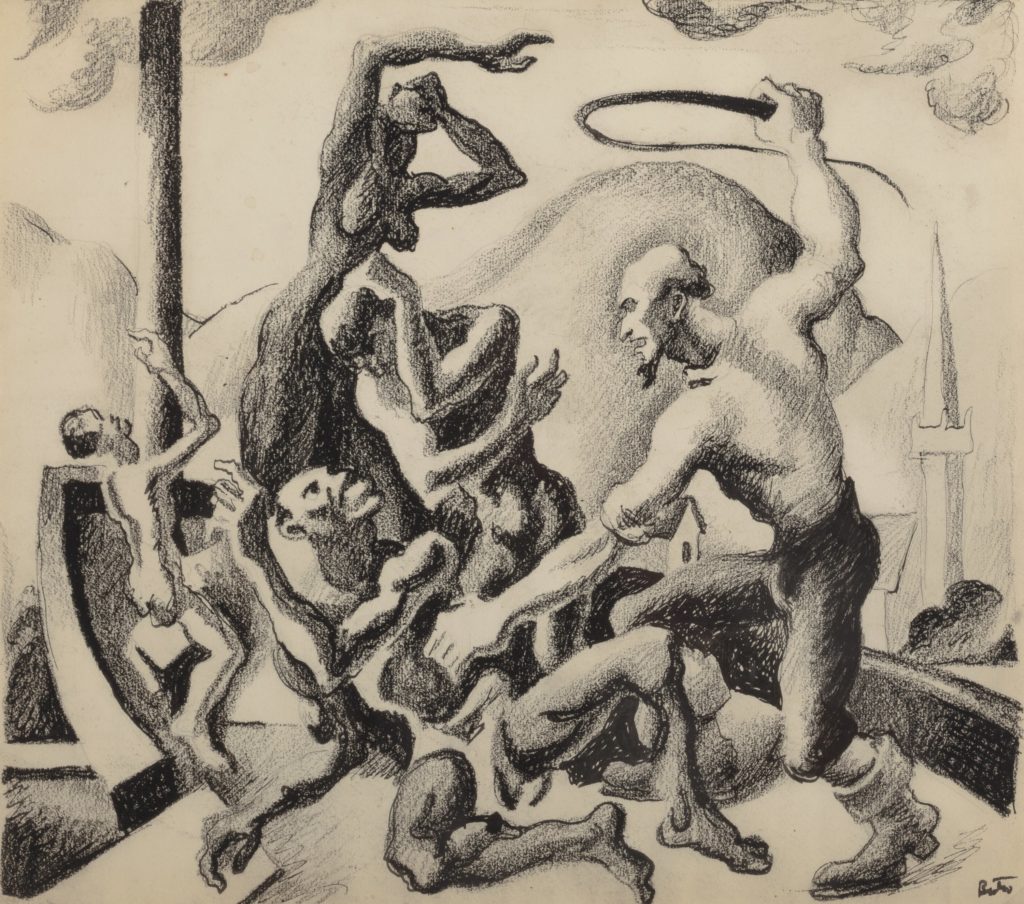

Slavery was the great exception to the rule of liberty proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence and established in the U.S. Constitution. The first African slaves (about 40 in all) were brought to the North American colony of Jamestown, Va., in 1619 to aid in the production of lucrative crops like tobacco.

By the time of America’s founding, the number had grown to 500,000, mostly in the five southernmost states. Slavery was never widespread in the North, but many profited indirectly by the practice. Between 1774 and 1804, all of the northern states had abolished slavery, but the “peculiar institution” remained absolutely vital to the South.

Even as the U.S. Congress outlawed the African slave trade in 1808, domestic trade flourished, and the slave population more than tripled over the next 50 years. By 1860, it was up to 4 million, primarily in cotton-production areas of the South.

One naive hope had been that slavery would slowly die as a simple matter of business economics. In 1776, Adam Smith (The Wealth of Nations) argued that the plantation system was uneconomic since slave labor cost more to maintain than laborers paid a competitive wage. But, in 1793, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, making slave-based production lower in cost. The insatiable demand for cotton from Europe was irresistible to the southern agrarian-based economy.

Overlooked in all of this was a brilliant insight by Smith. He noted that slavery ended in the Middle Ages in Europe only after the state and church became separate and strongly independent. His insight was that it is nearly impossible to end slavery in free, democratic forms of government, primarily because many of the legislators would also be slave owners and unlikely to act in ways that were not in their best interest.

Similar arguments later appear in the works of French philosopher Auguste Comte, known for his ideas regarding the “separation of the spiritual and the temporal.”

That was exactly the situation in the United States since many of the founders – most notably George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison – owned slaves and the South had always been dominated by self-interest. The obvious implication is that war was not only probable, but inevitable and unavoidable.

So the inexorable forces of profit versus human rights continued to accelerate, with only pauses, as the deeply conflicted country tried to find compromises (e.g. 1820) that simply delayed the inevitability of war. Kick-the-can strategies never achieve anything except temporary lulls.

Quite predictably, ours required a bloody civil war to (finally) reconcile the Constitution and an insidious practice of slavery that violated every principle that men of goodwill supported.

Both Smith and Comte tried to warn us, but their theories did not include any useful solutions, except perhaps to implement a kingdom … the very thing we were fleeing.

Even after 620,000 lives were lost in the Civil War, a number that exceeds all our other conflicts combined … and with the passage of 150 years … we are still struggling with race and inequality as our legislators try to find compromises.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].