By Jim O’Neal

By 1983, the population of the United States had increased to 232 million … and virtually everyone was watching television on a regular basis. On Feb. 23, over 50 percent of them (best estimate is 125 million) tuned in that night to the last episode of one of their all-time favorite shows, M*A*S*H.

For weeks, newspapers had run contests asking readers to suggest how the show should end. “M*A*S*H Bashes” were held in every major city and people donned old army fatigues to watch the show, primarily in bars. Seventy-one percent of viewers watching television that night helped “Goodbye, Farewell and Amen” become the most-watched show in history. (No. 2 is Cheers for its finale “One For The Road.”)

We were saying farewell, not just to beloved television characters, but to an era and anti-war spirit that the show had captured so brilliantly.

M*A*S*H, which ran for 11 years (1972-83), with 251 episodes that snagged nearly 100 Emmy nominations, is still broadcast in reruns and is considered one of network television’s finest efforts. It was based on Richard Hooker’s 1968 bestselling novel Mash: A Novel About Three Army Doctors and the 1970 feature film directed by Robert Altman. (Note: Some nitpickers claim it was really based on the failed film M*A*S*H Goes to Maine, which itself was based on Hooker’s 1972 book sequel.)

The story of a fictional Mobile Army Surgical Hospital near the front lines of the Korean War (technically a U.N. “police action”), the TV show was filled with the high jinks typical of the book and movie, yet it established its own tone of prickly intelligence, wit and sardonic warmth. In tackling the darker aspects of war, the show perfectly echoed a conscience-stricken America, deeply troubled by Vietnam. In reality, and with an exquisite touch of irony, the book’s author was a surgeon from Maine who served in a MASH unit in Korea and actually hated the show for its anti-war message!

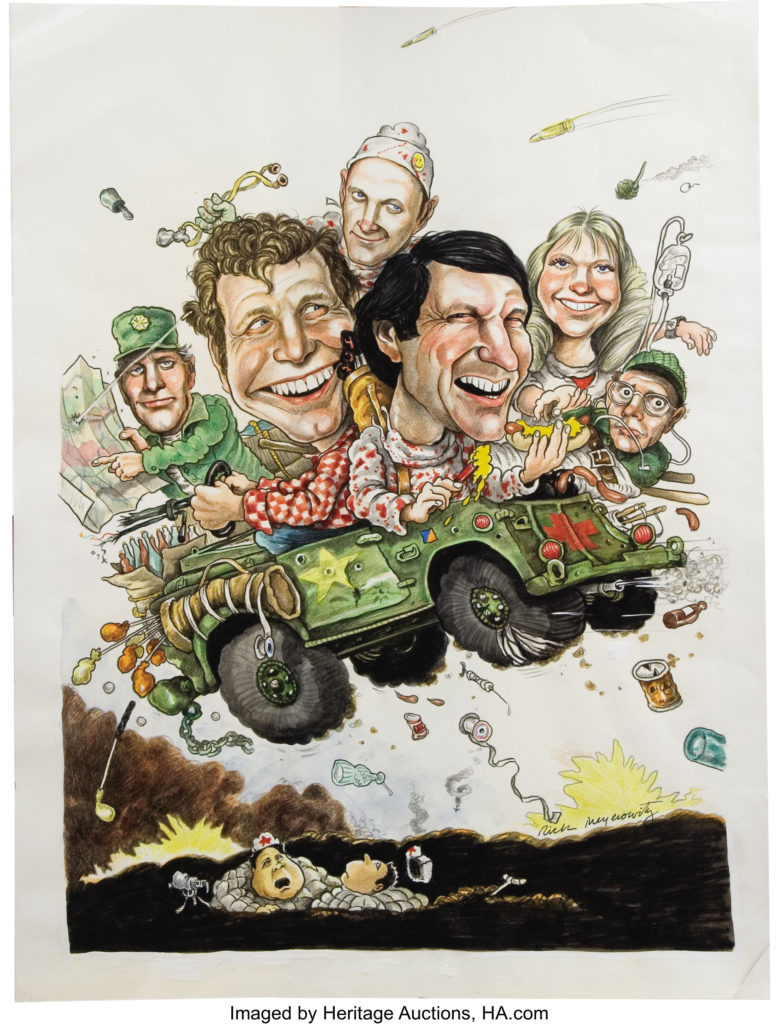

M*A*S*H creator, comedy writer Larry Gelbart, put the wise-cracking, womanizing, yet humane Benjamin Franklin “Hawkeye” Pierce (Alan Alda) at the center of the action. Sharing Hawkeye’s flea-bitten tent were fellow surgeons “Trapper” John McIntyre and Frank Burns, who was having an affair with Margaret “Hot Lips” Houlihan, the strong-willed head nurse. A favorite was Max Klinger, a cross-dresser who would try anything to get home. The cast changed over time, and finally even Gelbart left, exhausted from battles with network sensors.

The last episode, “Goodbye, Farewell and Amen,” which ran 2½ hours, was a remarkable culmination of everything the series represented: good, funny television drama that probed the ugly underside of war – in that last case, the savagery of peace in the closing days of Korea.

“What happened on the bus?” psychiatrist Sidney Freedman keeps asking Hawkeye, who in the final episode’s opening is in a mental institution.

Slowly, we learn that on July 4, after a day at the beach, the unit’s bus stopped to pick up refugees and wounded G.I.’s who told them to drive the bus into the bushes to hide from an enemy patrol. Hawkeye keeps hissing at a refugee woman, to keep her rooster on her lap quiet. The woman complies and eventually the repressed memory emerges … the woman has smothered her own child.

Hawkeye shakily returns to the 4077th and on the night of the armistice, one of the worst rounds of casualties is brought in. “Does this look like peace to you?” Margaret asks. Then over the PA system comes a litany of the war’s damage, ending with “2 million killed and 100,000 Korean orphans.” As the unit is broken down, each character gropes toward civilian life.

As Hawkeye lifts off in a helicopter, he sees down below on the deserted 4077, spelled out in stones, a message from his friend B.J. Hunnicutt: GOODBYE.

This last episode, considered the best in television history, was more than a goodbye. It was an example of how far serious and intelligent television can go, and a reminder that it very rarely does.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].