By Jim O’Neal

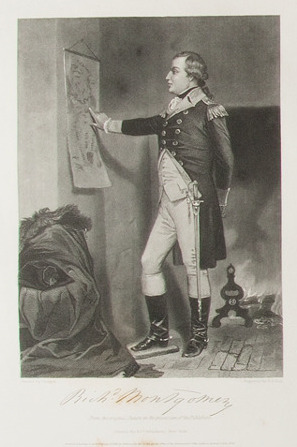

Richard Montgomery (1738-75) was a little-known hero-soldier born in Dublin, Ireland, who became a captain in the British Army in 1756. Later, he became a major general in the Continental Army after the Continental Congress elected George Washington as Commander in Chief of the Continental Army in June 1775. This position was created specifically to coordinate the military efforts of the 13 Colonies in the revolt against Great Britain.

Montgomery was killed in a failed attack on Quebec City led by General Benedict Arnold (before he defected). Montgomery was mourned in both Britain and America as his remains were interned at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City.

A remarkably diverse group of schools, battleships and cities named in his honor remain yet today. Montgomery, Ala., is the capital and second-largest city in the state; it’s where Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white passenger on Dec. 1, 1955, sparking the famous Montgomery bus boycott. Martin Luther King Jr. used Montgomery to great advantage in organizing the civil rights movement.

Montgomery was also the first capital of the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States when the first meeting was convened in February 1861. The first seven states that seceded from the United States had hastily selected representatives to visit the new Confederate capital. They arrived to find the hotels dirty, dusty roads, and noisy lobbyists overflowing in the statehouse. Montgomery was not prepared to host any large group, especially a large political convention.

Especially notable was that most of the South’s most talented men had already either joined the Army, the Cabinet or were headed for diplomatic assignments. By default, the least-talented legislators were given the responsibility of writing a Constitution, installing the new president (Jefferson Davis), and then authorizing a military force of up to 400,000 men. This conscription was for three years or the duration of the war. Like the North, virtually everyone was confident it would be a short, decisive battle.

Jefferson Davis was a well-known name, having distinguished himself in the Mexican War and serving as Secretary of War for President Franklin Pierce. Like many others, he downplayed the role of slavery in the war, seeing the battle as a long-overdue effort to overturn the exploitive economic system that was central to the North. In his view, the evidence was obvious. The North and South were like two different countries: one a growing industrial power and the other stuck in an agricultural system that had not evolved from 1800 when 80 percent of its labor force was on farms and plantations. The South now had only 18 percent of the industrial capacity and trending down.

That mediocre group of lawmakers at the first Confederate meeting was also tasked with the challenge of determining how to finance a war against a formidable enemy with vastly superior advantages in nearly every important aspect. Even new migrants were attracted to the North’s ever-expanding opportunities, as slave states fell further behind in manufacturing, canals, railroads and even conventional roads, all while the banking system became weaker.

Cotton production was a genuine bright spot for the South (at least for plantation owners), but ironically, it generated even more money for the North with its vast network of credit, warehousing, manufacturing and shipping companies. The North manufactured a dominant share of boots, shoes, cloth, pig iron and almost all the firearms … an ominous fact for people determined to fight a war. The South was forced to import foodstuffs in several regions. Southern politicians had spoken often of the need to build railroads and manufacturing, but these were rhetorical, empty words. Cotton had become the powerful narcotic that lulled them into complacency. Senator James Hammond of South Carolina summed it up neatly in his “Cotton is King” speech on March 4, 1858: “Who can doubt, that has looked at recent events, that cotton is supreme?”

Southerners sincerely believed that cotton would rescue them from the war and “after a few punches in the nose,” the North would gladly surrender.

One of those men was Christopher G. Memminger, who was selected as Confederate States Secretary of the Treasury and responsible for rounding up gold and silver to finance the needs of the Confederate States of America (CSA). A lawyer and member of the South Carolina legislature, he was also an expert on banking law. His first priority was for the Treasury to get cash and he started in New Orleans, the financial center of the South, by raiding the mint and customs house.

He assumed there would be at least enough gold to coin money and commissioned a design for a gold coin with the goddess of liberty seated, bearing a shield and a staff flanked by bales of cotton, sugar cane and tobacco. Before any denominations were finalized, it was discovered there was not enough gold available and the mint was closed in June.

This was followed by another nasty surprise: All the banks in the South possessed only $26 million in gold, silver and coins from Spain and France. No problem. Memminger estimated that cotton exports of $200 million would be enough to secure hundreds of millions in loans. Oops. President Lincoln had anticipated this and blockaded all the ports after Fort Sumter in April 1861. No cotton, no credit, no guns.

In God we trust. All others pay cash.

One small consolation was that his counterpart in the North, Salmon P. Chase, was also having trouble raising cash and had to resort to the dreaded income tax. However, both sides managed to keep killing each other for four long years, leaving a legacy of hate.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].