By Jim O’Neal

Chicago had a big opportunity buried deep within a challenging situation.

In the early 19th century, trade goods from the Great Lakes region could be shipped on three routes. The Erie Canal got goods to New York, the Saint Lawrence River to the ports on the northern Atlantic, or goods went south on the Mississippi River to New Orleans into the Gulf of Mexico. The last option was best for goods grown or mined around Lake Michigan or Superior.

One issue was the lack of a physical connection to the Mississippi or any of its tributaries. There was a geographically infuriating obstacle in the way: a relatively low plateau with a wide expanse. It was this barrier, just a few dozen feet high, that separated the growing lakeside city of Chicago from the rivers of the west.

As early as 1673, French-Canadian explorer Louis Jolliet had remarked how easy it should be to cut a small canal across the hilltop marsh and make a direct link to the mighty river. Although Jolliet knew very little about artificial waterways, he was aware of a giant canal being built in France, the Canal du Midi, a 150-mile structure linking the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. It had started six years earlier and would take another eight years to complete. But, surely a small waterway here in America would be “trivial.”

Wrong!

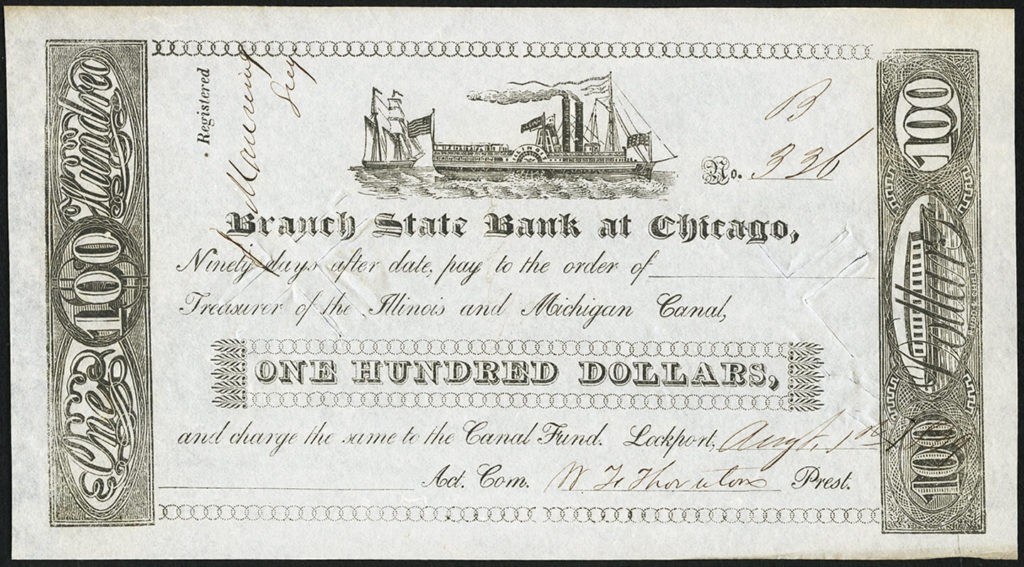

Neither the French nor British had pursued a project during their occupation of this land and only when Illinois become a state in 1818 did any serious discussions begin. Finally, on Independence Day 1836, the Illinois and Michigan Canal Company broke ground and digging began.

The implications for Chicago were enormous. Connect to the Mississippi and trade commerce would explode. Immigrant laborers were attracted in large numbers. In the 12 years it took to finish the canal, the population grew to 20,000 and six years later it had tripled.

It took 12 long years because the scope of the canal was much larger than anticipated. It became a fully formed waterway; 60 feet wide at the top, 26 feet wide on the bottom and 6 feet deep. However, it was 96 miles long, had 17 locks, four aqueducts, and a giant pumping station with feeder springs. It allowed vessels to pass without interruption from the Lakes to the new city of LaSalle on the Illinois River.

When the steamer General Thornton arrived in the middle of Chicago on April 19, 1848 (bringing a load of sugar from New Orleans), a cascade of other events followed: Chicago got its first telegraph, the Board of Trade opened, the first steam-powered elevator started unloading on the docks, and the first railroad connection was started.

Suddenly, Chicago was a vital fulcrum for commerce and business – conveniently located between East and West. Journeys that had taken fur traders three weeks or farmers 10 days could now be accomplished in less than one day’s sailing! A torrent of goods flooded in: lumber, wheat, corn, stone, salt and livestock for the packinghouses to fill the nation’s dinner tables.

People quickly found travel into the American interior delightfully uncomplicated since the first half of the journey was easily waterborne. Chicago’s new Grand Canyon was much more than the trivial ditch Jolliet had envisioned, but when gold was discovered in California the following year, the mass migration started, filling in the middle of the country as they went.

This was one “Big Dig” that paid off … big time!

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].