By Jim O’Neal

Vidkun Quisling is an obscure name from World War II. To those unfamiliar with some of the lesser-known details, “Quisling” has become a synonym for a traitor or collaborator. From 1942 to 1945, he was Prime Minister of Norway, heading a pro-Nazi puppet government after Germany invaded. For his role, Quisling was put on trial for high treason and executed by firing squad on Oct. 24, 1945.

Obviously better known are Judas Iscariot of Last Supper fame (30 pieces of silver); Guy Fawkes, who tried to assassinate King James I by blowing up Parliament (the Gunpowder Plot); and Marcus Junius Brutus, who stabbed Julius Caesar (“Et tu, Brute?”). In American history, it’s a close call between John Wilkes Booth and Benedict Arnold.

The irony concerning Benedict Arnold (1741-1801) is that his early wartime exploits had made him a legendary figure, but Arnold never forgot the sleight he received in February 1777 when Congress bypassed him while naming five new major generals … all of them junior to him. Afterward, George Washington pledged to help Arnold “with opportunities to regain the esteem of your country,” a promise he would live to regret.

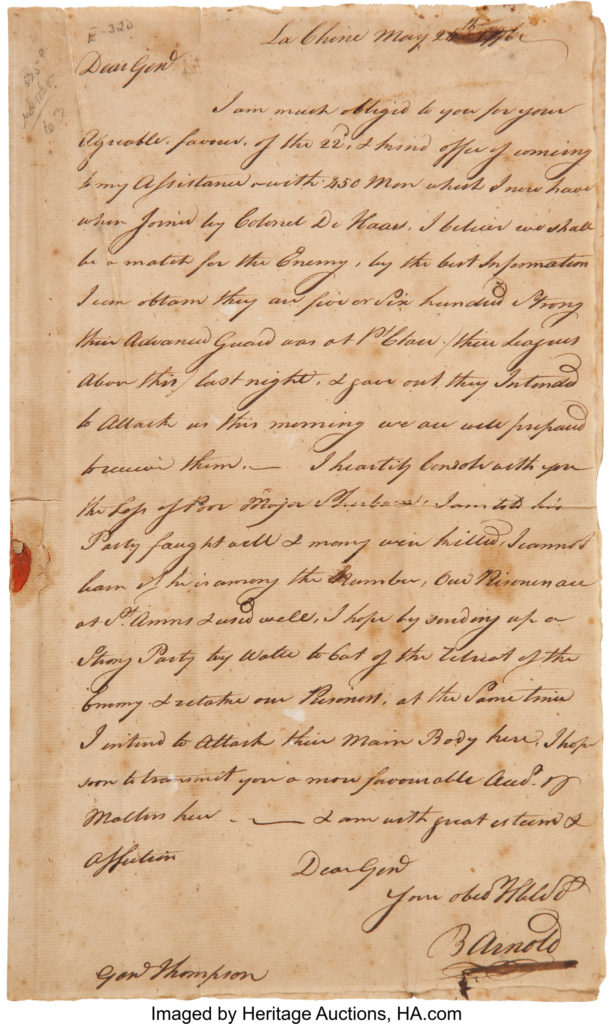

Unknown to Washington, Arnold had already agreed to sell secret maps and plans of West Point to the British via British Maj. John André. There have always been honest debates over Arnold’s real motives for this treacherous act, but it seems clear that purely personal gain was the primary objective. Heavily in debt, Arnold had brokered a deal that included having the British pay him 6,000 pound sterling and award him a British Army commission for his treason. There is also little doubt that his wife Peggy was a full accomplice, despite a dramatic performance pretending to have lost her mind rather than her loyalty.

The history of West Point can be traced back to when it was occupied by the Continental Army after the Second Continental Congress (1775-1781) was designated to manage the Colonial war effort. West Point – first known as Fort Arnold and renamed Fort Clinton – was strategically located on high ground overlooking the Hudson River, with panoramic views extending all the way to New York City, ideal for military purposes. Later, in 1801, President Jefferson ordered plans to establish the U.S. Marine Corps there, and West Point has since churned out many distinguished military leaders … first for the Mexican-American War and then for the Civil War, including both Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee. It is the oldest continuously operating Army post in U.S. history.

To understand this period in American history, it helps to start at the end of the Seven Years’ War (1756-63), which was really a global conflict that included every major European power and spanned five continents. Many historians consider it “World War Zero,” and on the same scale as the two 20th century wars. In North America, the skirmishes started two years earlier in the French and Indian War, with Great Britain an active participant.

The Treaty of Paris in 1763 ended the conflict, with the British winning a stunning series of battles, France surrendering its Canadian holdings, and the Spanish ceding its Florida territories in exchange for Cuba. Consequently, the British Empire emerged as the most powerful political force in the world. The only issue was that these conflicts had nearly doubled England’s debt from 75 million to 130 million sterling.

A young King George III and his Parliament quietly noted that the Colonies were nearly debt free and decided it was time for them to pay for the 8,000-10,000 Redcoat peacetime militia stationed in North America. In April 1864, they passed legislation via the Currency Act and the Sugar Act. This limited inflationary Colonial currency and cut the trade duty on foreign molasses. In 1765, they struck again. Twice. The Quartering Act forced the Colonists to pay for billeting the king’s troops. Then the infamous Stamp Act placed direct taxes on Americans for the first time.

This was one step too far and inevitably led to the Revolutionary War, with armed conflict that involved hot-blooded, tempestuous individuals like Benedict Arnold. A brilliant military leader of uncommon bravery, Arnold poured his life into the Revolutionary cause, sacrificing his family life, health and financial well-being for a conflict that left him physically crippled. Sullied with false accusations, he became profoundly alienated from the American cause for liberty. His bitterness unknown to Washington, on Aug. 3, 1780, the future first president announced Arnold would take command of the garrison at West Point.

The appointed commander calculated that turning West Point over to the British, perhaps along with Washington as well, would end the war in a single stroke by giving the British control over the Hudson River. The conspiracy failed when André was captured with incriminating documents. Arnold fled to a British warship and they refused to trade him for André, who was hanged as a spy after pleading to be shot by a firing squad. Arnold went on to lead British troops in Virginia, survived the war, and eventually settled in London. He quickly became the most vilified figure in American history and remains the symbol of treason yet today.

Gen. Nathanael Greene, often called Washington’s most gifted and dependable officer, summed it up after the war most succinctly: “Since the fall of Lucifer, nothing has equaled the fall of Arnold.”

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].