By Jim O’Neal

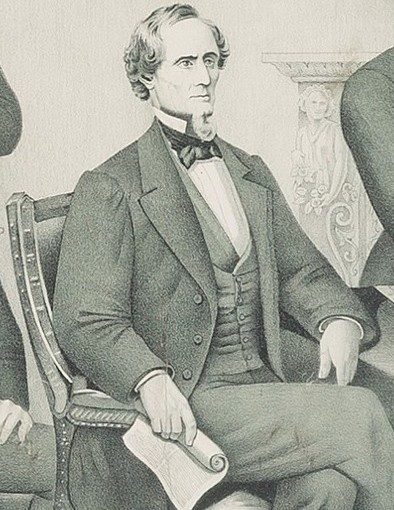

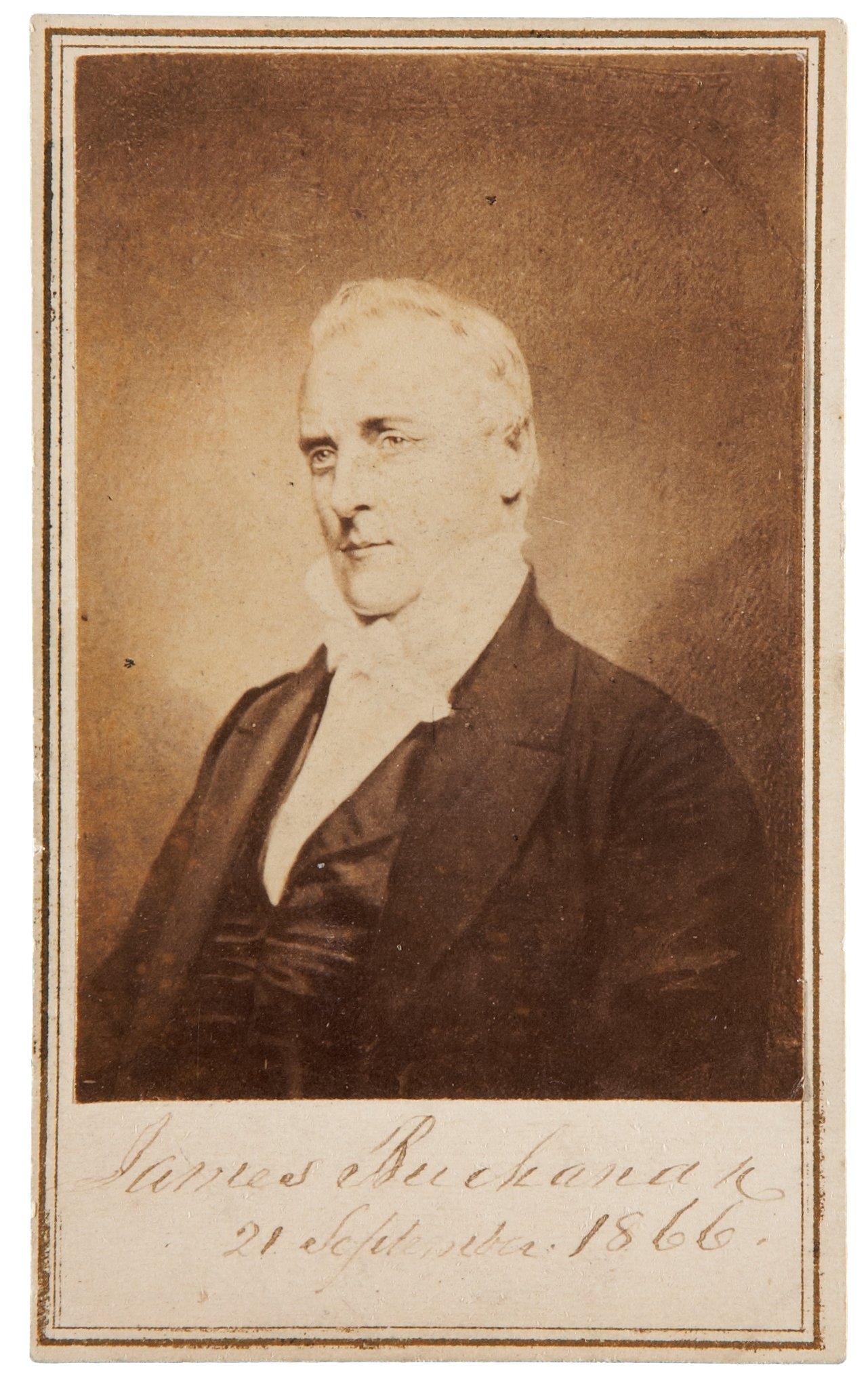

James Buchanan as a lame-duck president did nothing to stem the tide of disunion. He officially held the reins of power in the four-month period between the presidential election in November and Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration in March 1861, but he had lost any popular mandate to govern.

Secessionists had anticipated his indecision and cited it as confirmation of their argument that disunion would be peaceable. Buchanan – reasoning that just as secession was unconstitutional, so was any attempt by the federal government to resist it by force – preferred to leave the problem to the Republicans.

He sincerely thought they were responsible for the crisis, and he said as much in his last annual message of Dec. 3, 1860. His policy was simply to do nothing that might provoke an armed conflict with any seceding states.

Republicans initially denied the existence of any crisis. They were acutely aware of the pattern of Southern bluster and Northern concessions that had characterized previous confrontations, and they were not about to surrender their integrity as an anti-slavery party by yielding to Southern demands.

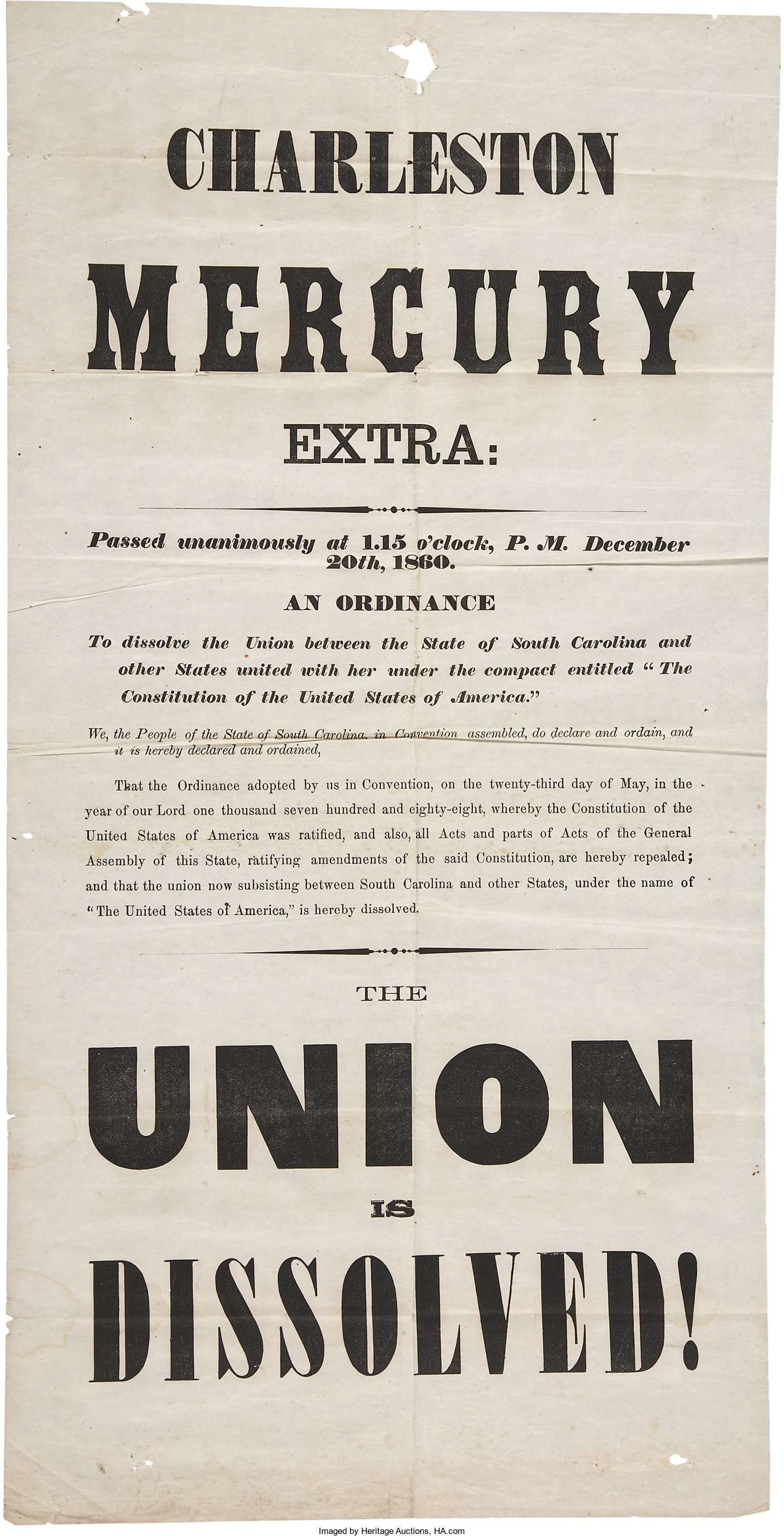

At Lincoln’s urging, they drew the line at sanctioning the territorial expansion of slavery. Such a sanction was a crucial feature of the Crittenden Compromise, a package of six proposed constitutional amendments that came out of a Senate committee led by John J. Crittenden of Kentucky in mid-December. Slavery would be recognized south of 36 parallel 30 degrees in all present territories, as well as those “hereafter acquired.” To a man, Congressional Republicans rejected what they interpreted as a blank check for the future expansion of slavery into Mexico and the Caribbean.

The collapse of the Crittenden Compromise in late December eliminated the already slim possibility that the drive toward secession might end with the withdrawal of just South Carolina. Still, when Lincoln took office on March 4, Republicans had reason to believe that the worst of the crisis was over.

February elections in the Upper South had resulted in Unionist victories after five states had called for conventions in January and the secessionists had suffered sharp setbacks in all the elections. By the end of February, secession apparently had burnt itself out.

Throughout March and April, the Union remained in a state of quiescence, but the pressure was too high. A core of secessionists were more eager for war than anti-slavery forces were to making concessions. Besides, everyone knew that if armed conflict began, it would be over very quickly. When it came, however, it was worse than anyone could have possibly imagined (sigh).

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].