“Our new Constitution is now established, and has an appearance of permanency, but in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” – Benjamin Franklin, 1789

By Jim O’Neal

I suspect Benjamin Franklin would be pleased that our Constitution has become the most revered document of our United States, but mildly surprised that the U.S. Internal Revenue Code – while undoubtedly much more prosaic – now symbolizes the highly intimate relationship between the people and their federal government. Detailed IRS regulations guide the filing of federal tax returns, an activity that is the most universal civic act in our history. Its 14,000 pages and 4 million words represent a remarkable achievement unparalleled by any government on earth.

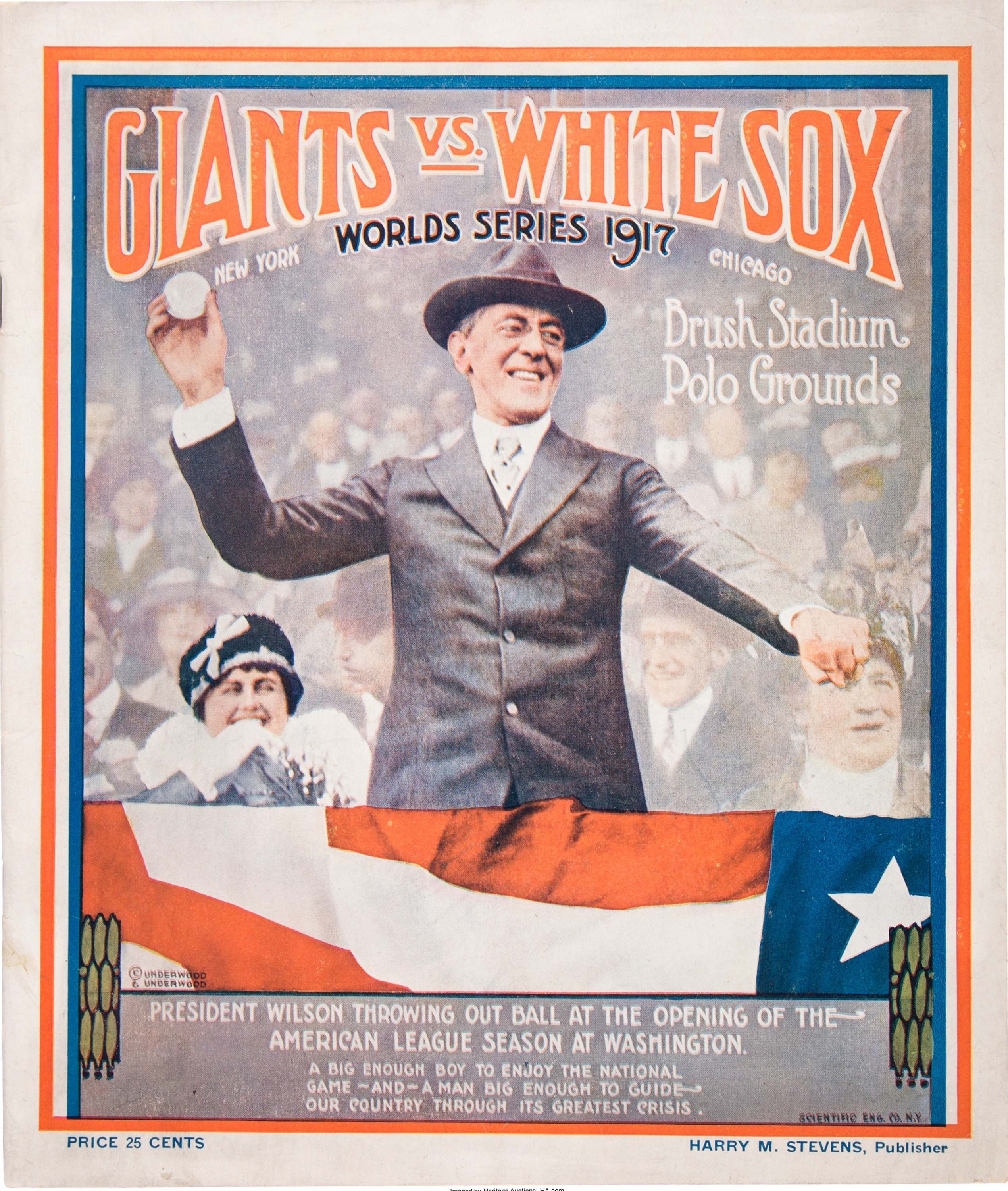

As the size and cost of government have grown, so has the size and difficulty of the tax return itself. In 1913, the first year the modern income tax was levied (an emergency income tax levied during the Civil War was allowed to expire in 1872), the top rate was 7 percent and then only for incomes over $500,000. The rate for people between $3,000 and $20,000 was just 1 percent, and below that zero. All but 1 percent of Americans were exempt from taxes. This was by design since advocates wanted a tax directed only at excess corporate and personal profits, not the wages of ordinary people. It was a way of reasserting the values of the early republic – now focused principally on equality – in reaction to gross inequities brought on by industrialization, and a way to force millionaire industrialists to share their wealth with society.

But WWI and the Great Depression increased the responsibilities of the federal government and rates took a quantum leap with the demands of WWII as the government took advantage of American patriotism. The number of tax filers rose to a point that what had been a “class tax” became a “mass tax.” The April 15 deadline is now a national rite, dreaded as much as it is observed. The complexity has become so pervasive that most filers require the aid of professional tax preparers. Looking back, it still seems remarkable that the income tax could have been extended to include so many people without creating a backlash. The wars helped, as did the success of government in defeating our enemies and the post-war economic growth. But the primary reason was that a new way had been devised to collect it.

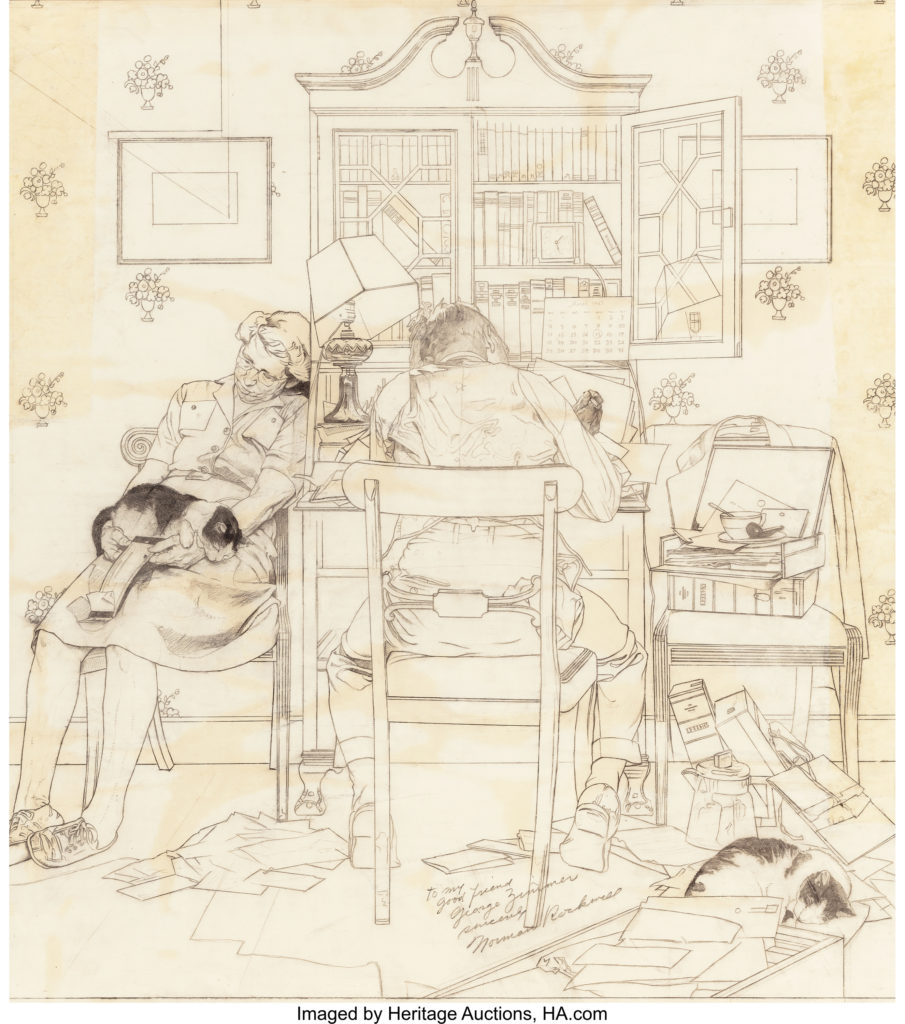

For that, the IRS can thank Beardsley Ruml, a mid-century Macy’s executive who came up with a plan to institute what is politely called “withholding.” Until 1943, income tax was paid each year in a lump sum and filers were expected to put aside the money to make the payment. Yet that year, when the number of wage earners included under the tax grew by nearly 35 million and the Treasury Department became nervous about how many were actually prepared to pay, Ruml offered an idea. Aware that customers in his store were comfortable buying big-ticket items when they could pay in installments, he suggested the government get businesses to collect the tax in small increments and report that amount to the employees and IRS each year for future reconciliation.

To get the public’s endorsement, he also suggested a tax amnesty for the previous year. Congress did just that by forgiving 75 percent of the previous year’s tax liability while they installed the machinery for the withholding that has operated ever since. To appreciate the profound shift that a broad-based income tax brought to the Treasury, just consider that in 1910, tariffs and excise taxes brought in more than 90 percent of federal monies; by the end of the century, income tax had replaced tariffs, providing 90 percent of the nation’s revenue, or $2 trillion! More importantly, it changed the debates – from regional tariffs or whiskey producers versus cattle growers, to which income levels should be taxed more. Class versus class and a “soak the rich” is always the first reaction to feed the insatiable appetite at every level of government.

As an elastic source of revenue, the income tax became a fundamental part of statism, a tool to be used in the interest of creating a more democratic social order. Look to Washington, D.C., today to see what this has wrought: a city bursting at the seams with lobbyists, industry organizations, tax lawyers and political advocacy groups. Any tall building will have a group with the word “tax” in its title, all working to shape policy and regulations. Yet despite our best efforts, we have become addicted to spending more than our revenue and simply saying “charge it.”

I suspect even Mr. Ruml would be surprised about the success of our “buy-now-pay-later” system that so closely resembles his Macy’s secret sauce.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].