By Jim O’Neal

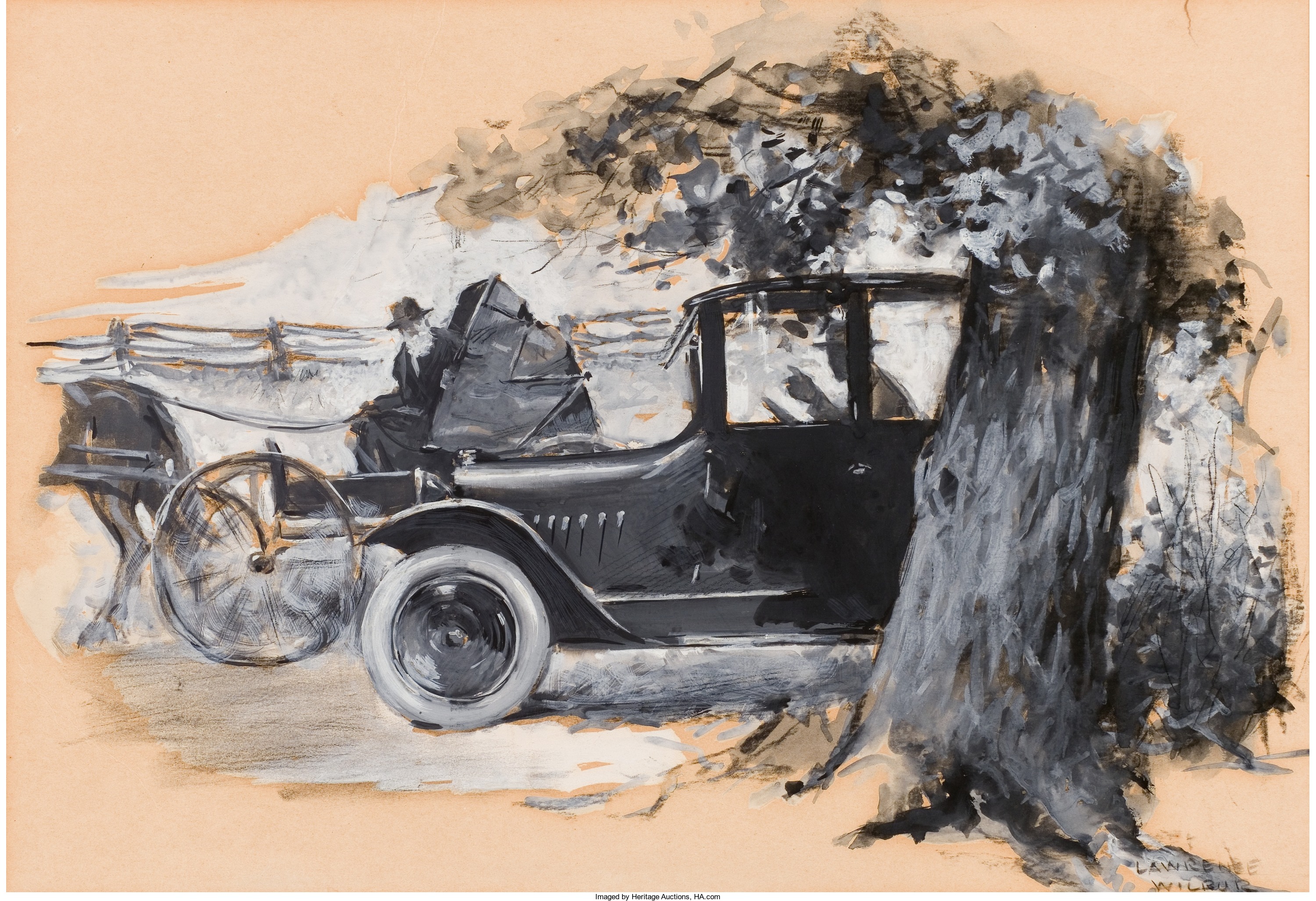

Automobiles have been around for a long time. Henry Ford built his first one in 1893 and his first Model T was completed in 1908. In 1920, there were already 8 million horseless carriages sputtering and rattling around the poorly charted “roads” of the American countryside, most of them Tin Lizzies purchased for the remarkably low price of $300.

But in the succeeding years of that decade, the mass rush to the automobile began to have its impact. By 1929, more than half of all American families had a car; by 1930, there were more cars on the streets of New York City than on the entire European continent.

The change was sudden and dramatic. The automobile was the first significant improvement in self-guided travel since the bicycle was introduced in Scotland in 1839 and had caused a similarly dramatic effect on the 19th century.

The burgeoning automobile age established a new sense of freedom and individuality; people no longer had to make their plans according to train schedules and they traveled by themselves instead of with hundreds of strangers. At the same time, it also established a new, wider sense of community. Small towns that existed miles from anywhere else were now connected to each other by roads, giving large groups of people access to first-rate medical care, higher quality education, and whatever else lay “down the road.”

Thanks to the car, thousands of suburban communities flourished, providing people with the luxury of homes surrounded by real grass, despite having to commute longer distances to their jobs in the city. This even led to tourism helping blend discrete regions and meld society together. Spurred on by demanding auto owners, building roads became a prime activity of government, second only to education.

And with each mile of road came something new.

The first motel in 1925 in San Luis Obispo, Calif. The first set of red lights in NYC (1922). The first shopping center in Kansas City in 1922. The first national road atlas (Rand McNally, 1924). The first public parking garage in 1929 in Detroit.

One out of eight people who owned cars actually worked in the industry, building them or producing the required tires, oil and steel. It led to the eight-hour workday, the five-day workweek and safer working conditions. It even changed how people thought about money and credit. Buying a car was a real debt and by the end of the 1920s, more than 60 percent of all sewing machines, vacuum cleaners and refrigerators were bought on purchase plans, and one-third of all furniture, including radios!

A consumer-based economy would be a powerful force and today represents 70 percent of our total economic output.

So the next time you’re stuck in a traffic jam or cursing about too many potholes, consider the alternative and the rich history that is included.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].