By Jim O’Neal

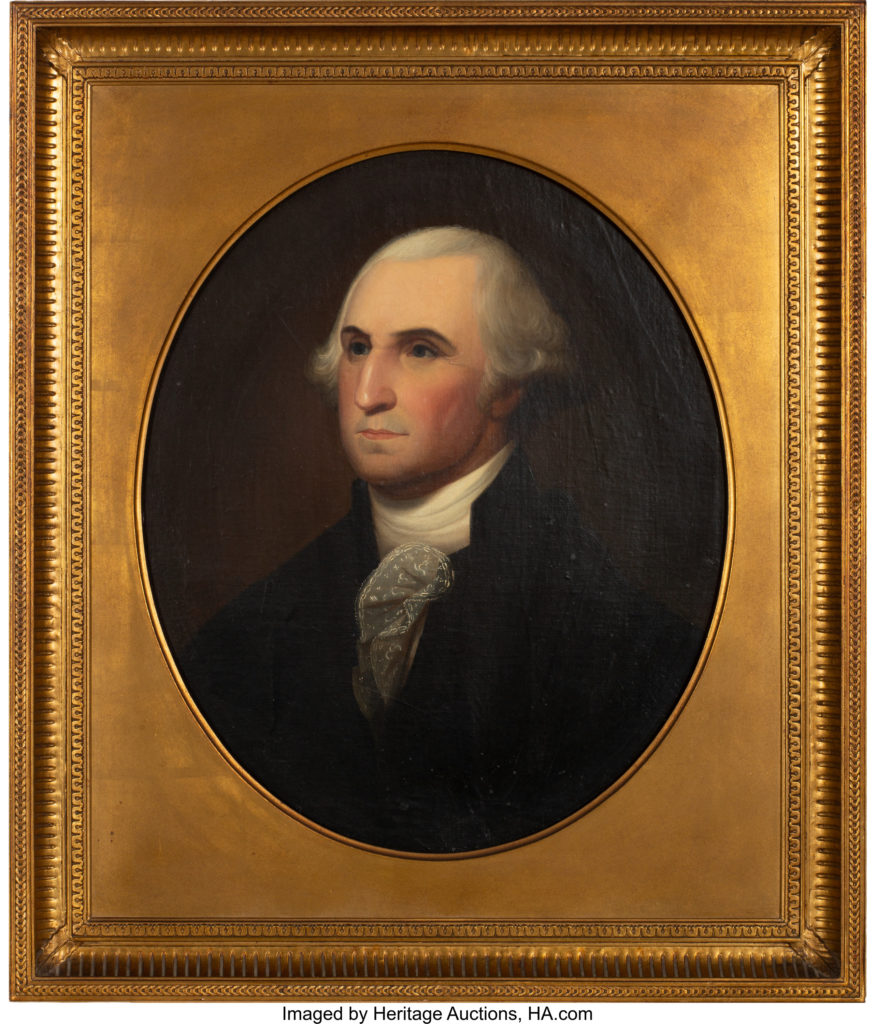

The date was April 30, 1789, and the highly respected commander of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War was ready to take the oath as the first president of the United States. The election had taken place much earlier in January, but electoral votes had not been counted until April 5.

General George Washington, who also had served as the presiding officer at the Continental Convention of 1787, was unanimously elected to the highest office in the new nation. He had to travel from his home in Virginia to New York City for the formal inauguration.

Robert Livingston, chancellor of New York, administered the presidential oath of office at Federal Hall across from the New York Stock Exchange. This site was home to the first Congress, the Supreme Court and executive offices. President Washington then retired to the Senate Chamber where he delivered the first inaugural address to a joint session of Congress. Observers commented he was mildly embarrassed and noticed an almost imperceptible tremble; possibly due to the significant historic relevance of the occasion.

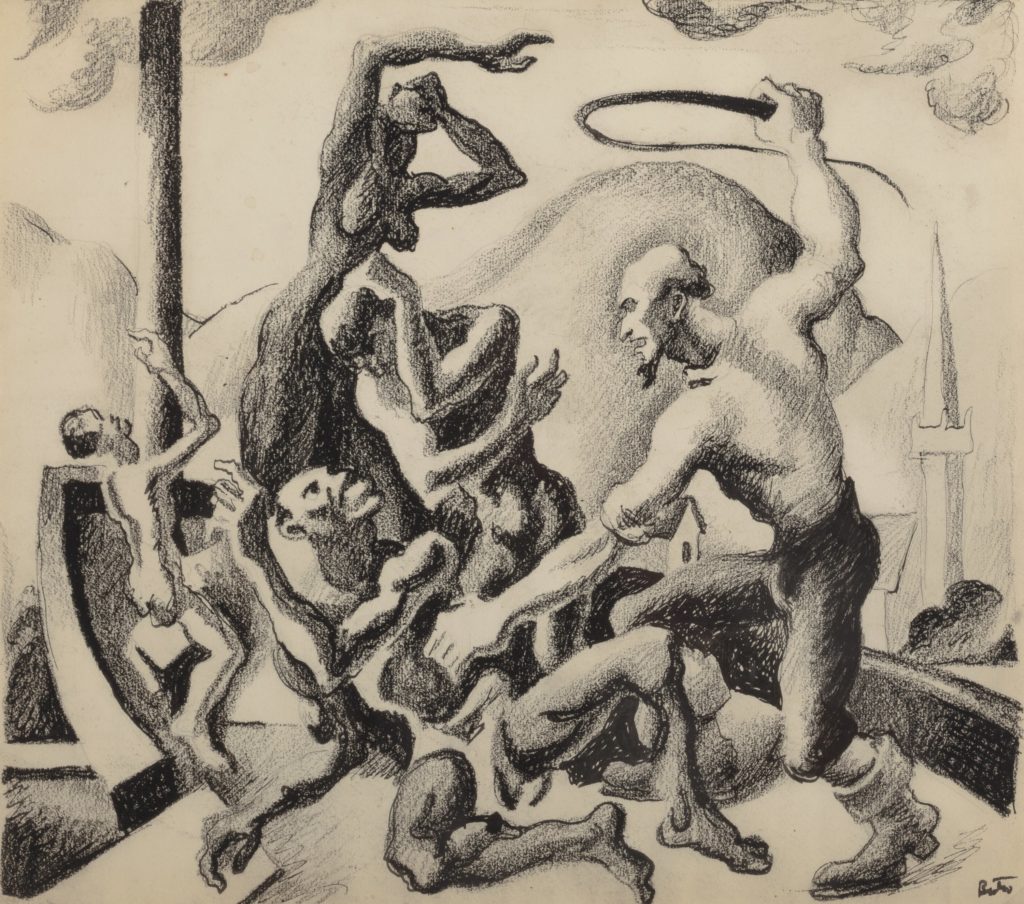

Two blocks away at 75 Wall Street now stands a 42-story modern structure of marble, glass and steel. This luxurious condominium was converted from office space in 2008. It sits at the water’s edge of the Hudson River, atop an old slave market, where people were bought and sold for over 50 years (1711-62).

For Dutch and Spanish slave-traders, who controlled the transatlantic trade at the time, there were far superior markets for the sale of slaves. For one, the sugar plantations in both Spanish America and Portuguese Brazil required hundreds of thousands of slaves.

Given the insatiable European demand for sugar, it made little sense for slave-traders to undertake the additional time to travel up the North American coast to service what was considered a small speculative market. A slave ship could make a round trip between West Africa and Brazil in the same time it would take just to reach Virginia one-way. Compounding the cost were the death rates a longer journey would impose on their human cargo. This was a thriving business and decisions were made based on profitability.

Another factor was that England’s American Colonies were not willing to pay a premium since there was an adequate supply of Europeans willing to serve as indentured servants. As a result, the transatlantic perimeter of the booming slave market essentially ended at the sugar-growing islands of the Caribbean.

In 1788, the year before Washington’s inauguration, the founders recognized that they would have to include language protecting slavery in order to get the necessary state votes to gain approval of the proposed U.S. Constitution. Perhaps James Madison – “The Father of the Constitution” – was the one who accomplished this without using either the words “slaves” or “slavery” (they do not appear until later with the 13th and 15th Amendments). Instead, the reference was to a person “held to service” or “bound to service.”

In a compromise, the Constitution ordered Congress to pass a regulation to abolish it by 1800. A special committee extended the deadline to 1808 to allow a gradual 20-year phase out. They assumed (wrongfully) that slavery would become uneconomic and just naturally die out. In fact, it continued to grow. The 1790 census reported a U.S. population of 4 million, including 700,000 slaves.

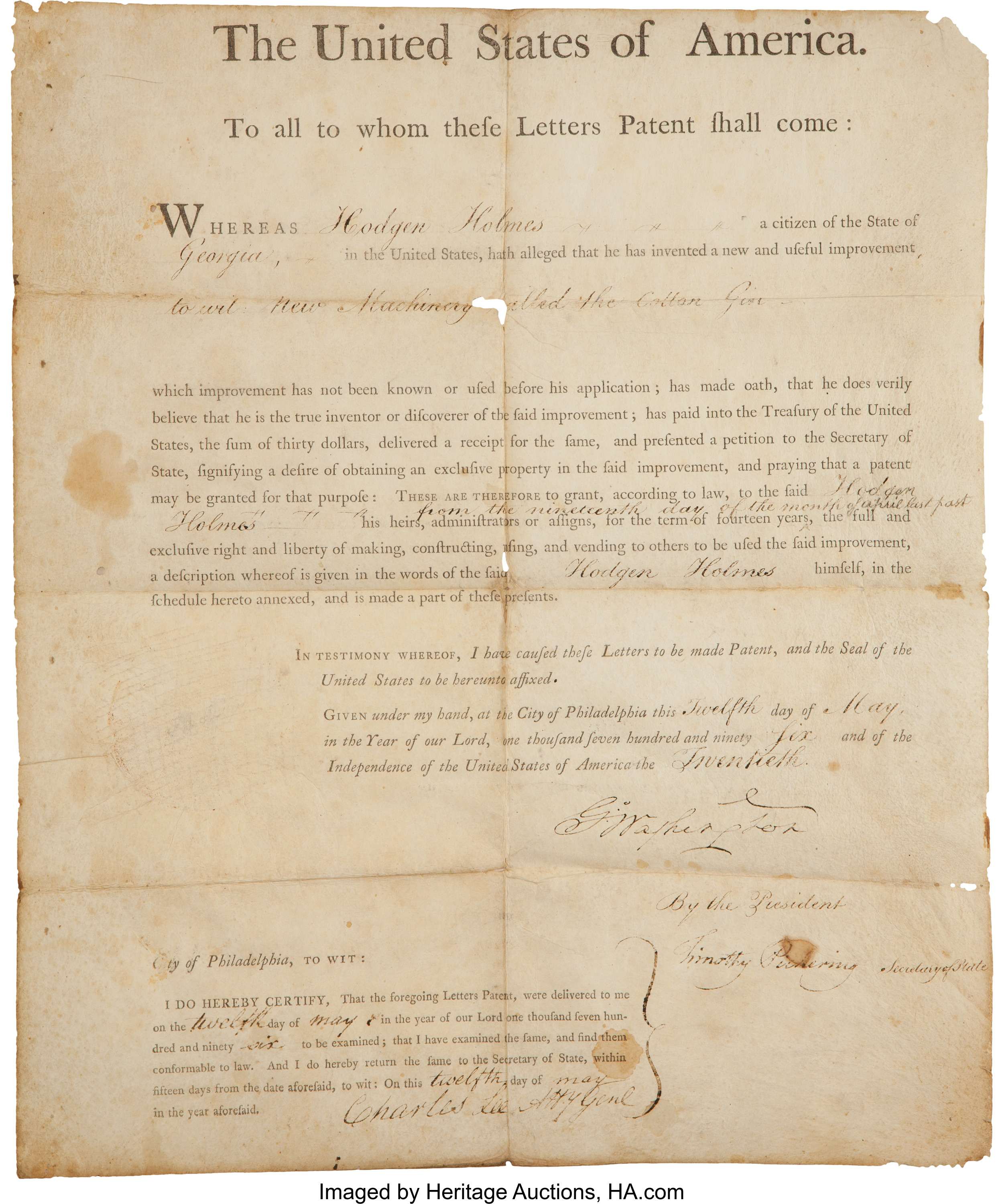

Then, in 1793, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, which fueled a massive increase in cotton production. Slave plantations were America’s first big business, not the railroad, as some believe. Ten of the first 12 presidents were slaveholders, and two of the earliest Chief Justices.

The slave trade was one of Great Britain’s most profitable businesses. From 1791 to 1800, British ships made 1,300 trips across the Atlantic with 400,000 slaves. And then from 1801 to 1807 another 266,000. During the whole of the 18th century, the slave trade accounted for 6 million Africans. Britain was the worst transgressor, responsible for 2.5 million of the total.

In 1807, the U.S. Congress passed the slave act to “prohibit the transportation of slaves into any port … from any foreign place” (starting in 1808, as directed by the Constitution). However, it did not ban the trading of slaves within the United States. With an estimated 4 million slaves in the country (plus children born into slavery), this resulted in a self-sustaining model that did not require importation, which was now abolished.

The nation continued to evolve with a Southern agrarian society heavily dependent on slave labor while the North pursued industrialization. The constant debates over abolition simply shifted to how new territories and states would enter the Union … as free or slavers. This delicate balance was not sustainable and virtually everyone knew how it might end. It was almost inevitable that no permanent agreement was possible.

We know the implications of the great Civil War that was required to permanently stop slavery in the United States and the difficulties during the post-war reconstruction era. We can wonder about the progress in civil rights during the 20th century. But how do we explain why we are still so divided racially?

I was eager to hear the recent presidential debates, expecting discussions about climate change, health care, immigration, inequality and impeachment. Instead, issues like reparations, asylum, abortion and even forced busing in the 1970s took center stage. Had I dialed 2020 and ended up in 1820 in a Twilight Zone episode?

Maybe Pogo was right after all: “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].