By Jim O’Neal

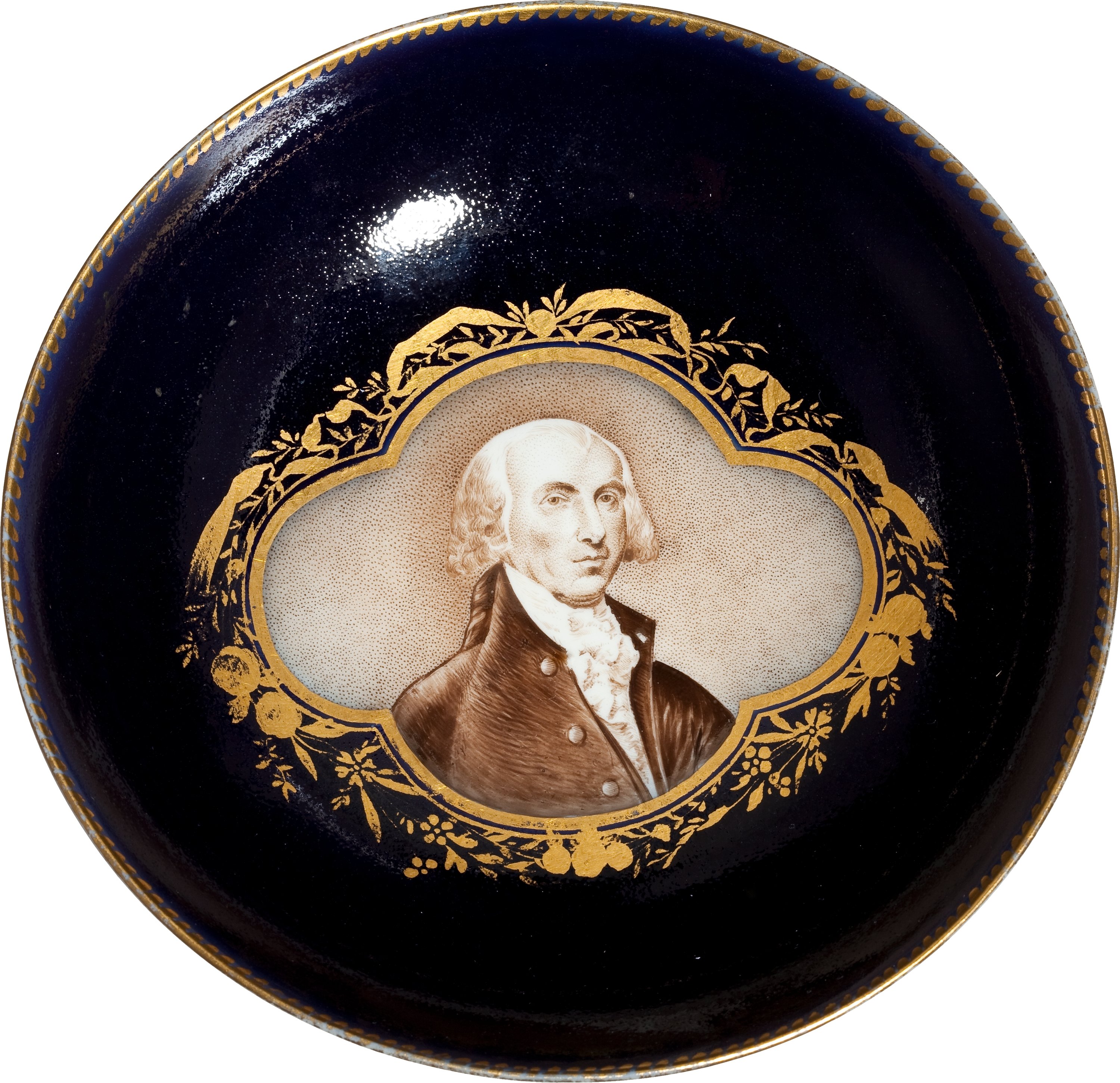

When a discussion of First Ladies occurs, the names of Dolley Madison, Eleanor Roosevelt and Jackie Kennedy Onassis are invariably among the first to be named. However, thanks to David McCullough’s splendid book (and TV mini-series) on John Adams, Abigail Adams (wife of one president and mother of a second) has gained long-overdue respect. Her wisdom, wit and persistent advocacy for equal rights for women was both fresh and modern.

The Adams marriage is well-documented due to an abundance of personal correspondence. She is also particularly associated with a March 1776 letter to John and the Continental Congress requesting that they “remember the ladies, and be more generous to them than your ancestors!”

As the first First Lady to reside in the White House, she was in a perfect position to lobby for women’s rights, especially when it came to private property and opportunities for a better education. After all, mothers played a central role in educating the family’s children. The more education she had, the better educated the entire family. It was this type of impeccable logic that made her so persuasive.

Had John won a second term, women’s progress would have been a big beneficiary with four more years of Abigail’s influence on policy-makers.

Abigail Adams is also given full credit for the total reconciliation of two long-time political enemies: Thomas Jefferson and her grouchy husband. They finally resumed their correspondence, which lasted right up until their same-day deaths on July 4, 1826 – the 50th anniversary of the founding of the nation.

That same year (1826), Varina Howell was born in rural Louisiana. Her grandfather, Richard Howell, served with distinction in the American Revolution (1775-1783) and would become governor of New Jersey in the 1790s. Her father fought in the War of 1812 and then settled in Natchez, Miss. Varina would later jokingly call herself a “half-breed” since she was born in a family with deep roots in both the North and South.

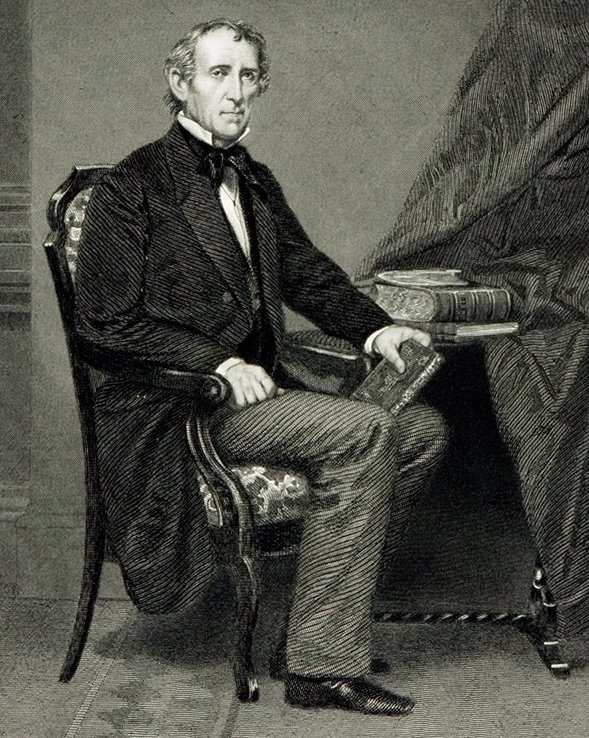

Jefferson Davis (1808-1899) was another prominent example of people who had deep ties to both the North and South, both in government and the military. In September 1824, he entered the U.S. Military Academy (West Point). He was in the middle of his class and was an infantryman 2nd Lieutenant in 1828. He married Sarah Taylor, daughter of President Zachary Taylor. However, they both contracted a fever and she died three months later. Deeply depressed, he lived in seclusion on his plantation until elected to Congress.

When the Mexican War started, he joined his ex-father-in-law’s army at Camargo, Mexico. Davis and his Mississippi riflemen did heroic duty. Davis was wounded at the Battle of Buena Vista and returned to the United States to find himself a hero. He was appointed to fill an unexpired U.S. Senate term. He was re-elected in 1850, gained prominence and made an unsuccessful bid to be governor. Newly elected President Franklin Pierce added him to his Cabinet as Secretary of War. Pierce had a problem with alcohol and relied on Davis to substitute when needed.

Inexorably, he was drawn into the vortex over the slavery issue. He spoke often of his love for the Union and even as the moral issues grew, he still felt the Union was safe, despite being fully aware of the growing political storm clouds. Devoted to the nation by lineage, history and patriotism, he was torn by the compact theory of the Union. These tenets held that the states were in fact sovereign, but they had yielded it by joining the Union and had to secede to reclaim it. He argued for stronger states’ rights within the Union, while urging moderation and restraint to save the Republic.

In December 1860, he was appointed to the Senate Committee of Thirteen, charged with finding a solution to the growing crisis. Davis ultimately judged the situation as hopeless and (reluctantly) advised secession and the formation of a Southern Confederacy.

Weary, dejected and ill, Jefferson Davis made a farewell address to the Senate on Jan. 21, 1861, emphasizing the South’s determination to leave the Union. Disunion was finally a stark reality. He and his family left Washington, D.C., and returned to Mississippi. It was there that he learned of his election as president of the Provisional Government of the Confederate States of America.

The Confederate guns began firing at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861.

War began.

In one of the Civil War’s richest ironies, the second Mrs. Jefferson Davis – his wife of 16 years – was openly critical of secession, calling it foolish and predicting the Confederacy would never survive. As the first First Lady, she characterized her time as the worst four years of her life. She told her mother the South did not have the resources to win and when it was over, “She would run with the rest!”

She did run to Manhattan and supported herself writing columns for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. That baby born in 1826 had fallen in love with Jefferson Davis and became Varina Howell Davis. The only First Lady of the Confederacy died in 1906 and her tombstone reads simply “AT PEACE.”

Considering the wisdom of Abigail Adams and Varina Davis, maybe it’s time for a First Gentleman.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].