By Jim O’Neal

In 1968, we were living in San Jose when national politics got complicated after President Lyndon Johnson made a speech that concluded, “Accordingly, I shall not seek and will not accept the nomination of my party for another term as your president.”

The date was March 31 and less than a week later, on April 4, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. The assassin, James Earl Ray, was on the loose and believed to have fled the country. Later, he would be apprehended at London’s Heathrow Airport and extradited to face first-degree murder charges. He pled guilty in return for a 99-year sentence and died in 1998 while still in prison.

The year had started off with an upset on Jan. 20 when the University of Houston, led by Elvin Hayes, defeated top-ranked UCLA, 71-69, in the Astrodome before 52,693 fans. It had been billed as the “Game of the Century” and was the first NCAA basketball game to be nationally televised in prime time, ultimately leading to “March Madness.” Although UCLA would go on to thrash Houston in the semi-finals (101-69) and defeat North Carolina in the championship game, the loss to Houston snapped a 47-game winning streak. Coach John Wooden simply commented, “I guess we’ll just have to start over.” From 1971 to 1974, UCLA won another 88 straight games.

Ten days after the UCLA upset, on Jan. 30, 1968, about 80,000 enemy troops launched a surprise attack on over 100 cities and towns in South Vietnam. It was the single most lethal day in terms of killed or mortally wounded U.S. military troops. Although the war would grind on for another six years, the “Tet Offensive” would turn out to be the beginning of the end, since it put the war into 50 million Americans’ living rooms every night on all three TV networks, which dutifully announced all the Viet Cong that had been killed. Even then, I never understood the logic on keeping track of enemy KIA and territory gained in the vain hope it would somehow boost public support (especially since it was the same territory we had won six weeks previously). It seemed analogous to fighting the Battle of Gettysburg (once a week) and then reporting on whether the North or South had won.

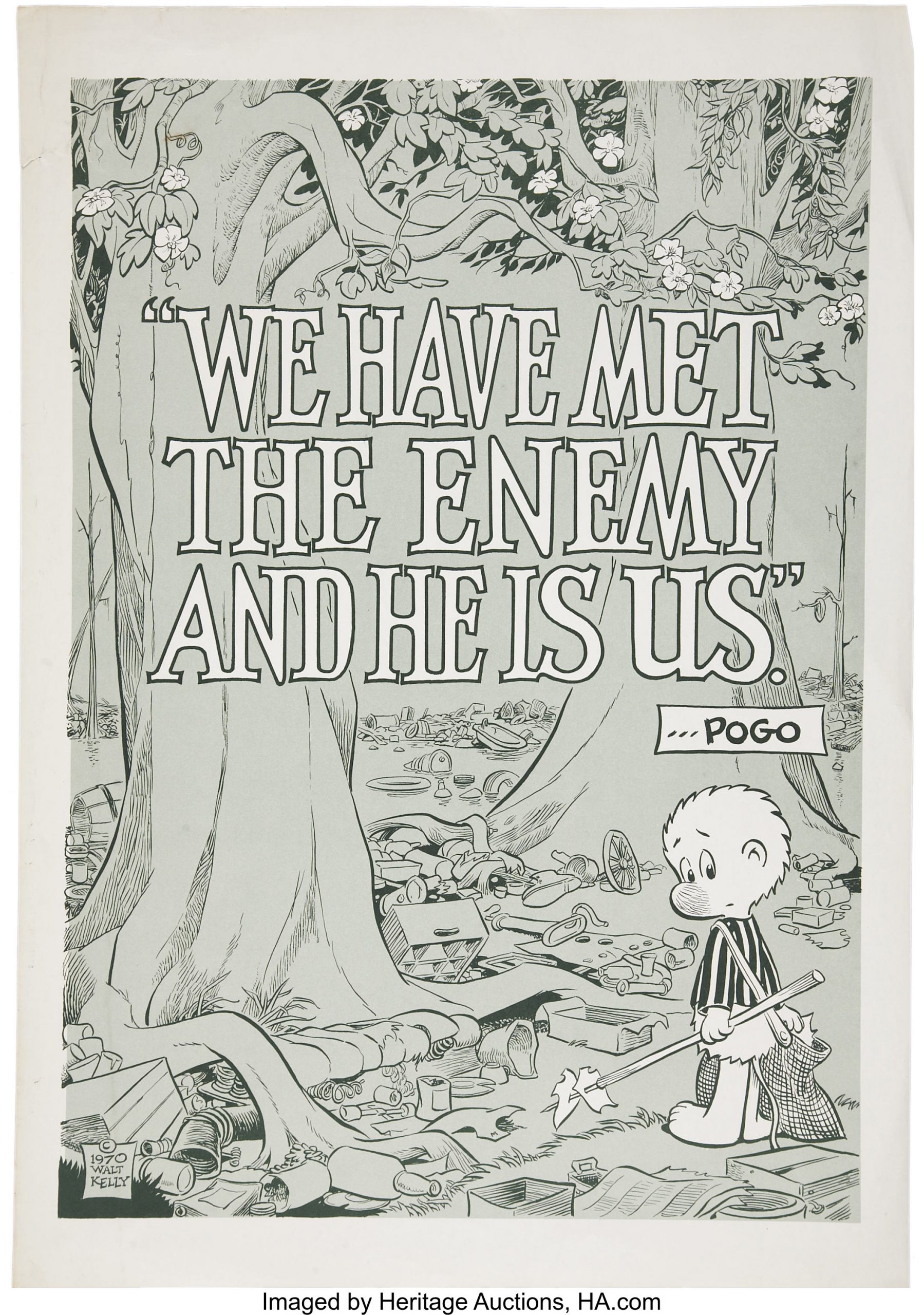

After the April murder of MLK, a wave of shock and distress spread across the nation, with riots and burning in more than 100 cities. Then two months later, disaster struck again when Bobby Kennedy was killed on June 5 at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. Tensions over Vietnam and Civil Rights were at a dangerous level and America’s leadership was being questioned. Walt Kelly’s frequently quoted Pogo line from that era – “We have met the enemy and he is us” – captured the mood of the country.

In August, we had dinner at the five-star Stanford Court Hotel on California Street on Nob Hill. Our host told us an amusing story about their last visit to the restaurant. Without mentioning any names, he explained that during dinner, the wife of his client had slipped a plate from the table into her handbag. Nothing was said, but when the check came, there was one line listed: “One dinner plate $75.” In a perverse way, it eased my concern that discretion and gentility were being eroded during all the domestic chaos.

Later I would learn that the hotel had been built on the same site that Leland Stanford (1824-1893) had built his magnificent mansion, which was legendary for its luxury and art collection. Finished in 1876 for the astonishing cost of $2 million, it was perched on two superb acres surrounded by a grand wall of basalt and granite. The Stanford manse was among the most elegant in the nation, but had been destroyed by fire in the 1906 earthquake.

Leland Stanford was one of the Big Four responsible for building the Central Pacific railroad that started in Sacramento and met the Union Pacific at Promontory Point, Utah, in 1869. This was the joining of the first Transcontinental Railroad that completed an “iron belt” around the country. Leland Stanford and his wife Janie are responsible for creating Stanford University in honor of a son that died. Leland and his cronies – Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker and Collis Huntington – were well known in 19th century history as “Robber Barons” and Stanford’s correspondence leaves no doubt that he used every trick in the book to cheat his partners, investors, the government and employees.

I suspect he never thought about stealing the silverware or china from restaurants.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].