By Jim O’Neal

On Nov. 19, 2007, I watched Charlie Rose interview Jeff Bezos about the new Kindle that debuted that day and sold out in 5½ hours. Books had been the last bastion of analog holdouts, although there were lots of Ebooks for sale.

The Kindle was something new.

It was a light (10 ounces) device that didn’t require a computer and would store up to 200 books in a library. One hundred and one of the 112 New York Times bestsellers were already available for $9.99, in addition to all major newspapers and magazines. You could order it from Amazon.com for $399 and when it arrived, it automatically recognized the user. Plus, there were lots of other cool features like a 250,000-word dictionary, access to Wikipedia and its 400 million pages, and you could read the first chapter of any book for free before deciding to buy it.

I immediately ordered mine and there was already a two-month waiting time. It is still around somewhere gathering dust, but my new Kindle is on my iPad (with an audio feature).

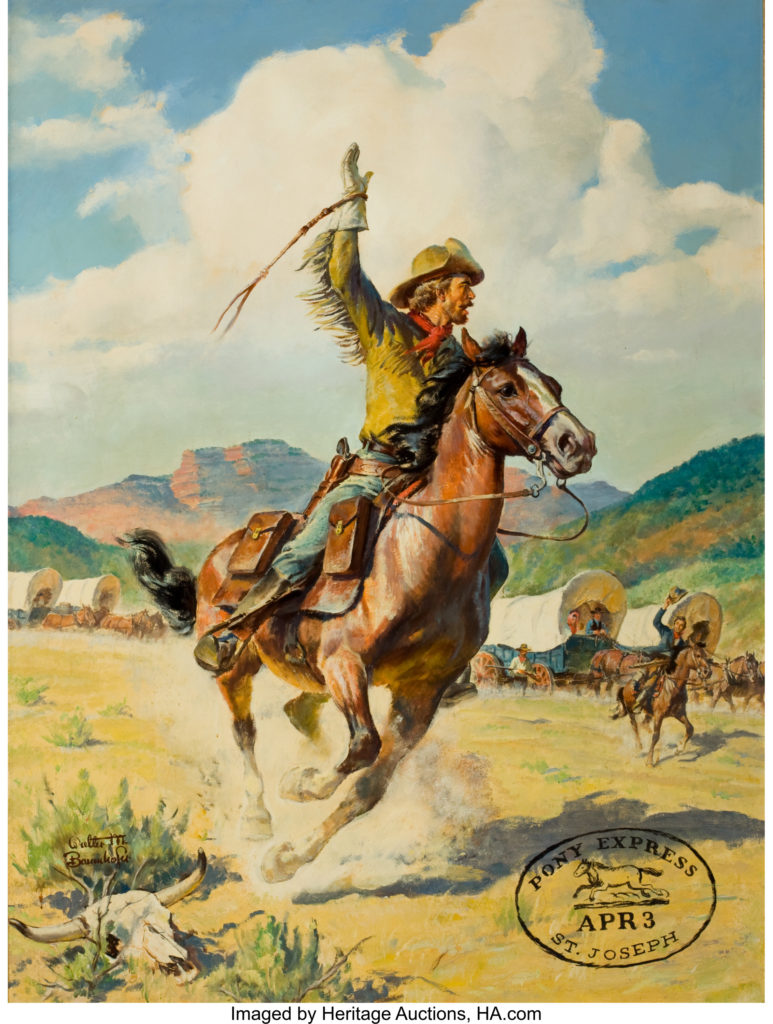

I guess we have always been an impatient culture with the “need for speed” in our DNA. Until the spring of 1860, it took 20 days for mail to get from St. Joseph, Mo., to Sacramento … far too long for most merchants and businessmen. Stagecoaches were just too slow until one of them – Russell, Majors and Waddell of Leavenworth, Kan. – came up with an idea to cut the delivery time by 50 percent.

For a fee of $2 to $10 per ounce, depending on the distance, you could use their new innovative mail service: the Pony Express. Starting on April 3, 1860, every Wednesday and Saturday one rider on horseback would leave at noon from Sacramento heading east, and another at 8 a.m. from St. Joseph heading west. Averaging about 8 miles an hour, every 10 miles or so, they would change horses at a relay station and continue at breakneck speed.

The typical payload of 20 pounds of letters was tucked into a Mexican mochila (knapsack) with four cantinas (locked pockets) for the oiled silk-wrapped letters that kept them dry when the rider inevitably had to cross streams or rivers. The mochila was designed to slip over the saddle horn and the rider sat on it until the next change of horses. Every 75 to 80 miles was a “home station,” where the incoming rider would pass the mochila to a fresh rider and then bunk down until the mail arrived from the opposite direction. Then, somewhat rested, he was off again, back the way he came.

The young hell-bent for leather riders intrigued the nation and their dedication became a staple for many bedtime stories. Some children heard the tale about 19-year-old Jack Keetley, who rode 340 miles in 31 hours non-stop until taken from the saddle … sound asleep. Fifteen-year-old William Frederick Cody was one of the daring young riders who would later become famous as Buffalo Bill with his own traveling Wild West show.

Still, speed was what mattered and the formal record for the central route’s 1,966 miles is 7 days and 17 hours. This was of special significance since it allowed California newspapers to publish President Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address. The Pony Express was, in every way, about speed. Even its history went by in a flash— 19 months, 2 weeks, 3 days and kaput! The bold experiment was finished, partially because it was costing about $30 a letter, but it was really just another victim of a new technology.

The ride lasted from April 3, 1860, to Nov. 20, 1861 … 596,501 miles, 30,700 pieces of mail and only one lost mochila! The Pony Express and its 80 dedicated riders, 400 horses and 190 relay stations all became irrelevant on Oct. 21, 1861, with the completion of the transcontinental telegraph line. That pattern of one innovation, one technology, giving way to another seems to be accelerating as our impatience and expectations continue to grow.

I just ordered four C batteries from Amazon and discovered they won’t be here until tomorrow (bummer!).

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].