By Jim O’Neal

In 1966, the American Society of Civil Engineers started a new honor category, “Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks.” The Bollman Truss Railroad Bridge in Savage, Md., was the first to receive this distinction and it remains the only example of an all-metal bridge design used on a railroad. Eventually, they got around to the Brooklyn Bridge and it was added in 1972 as the 27th project recognized.

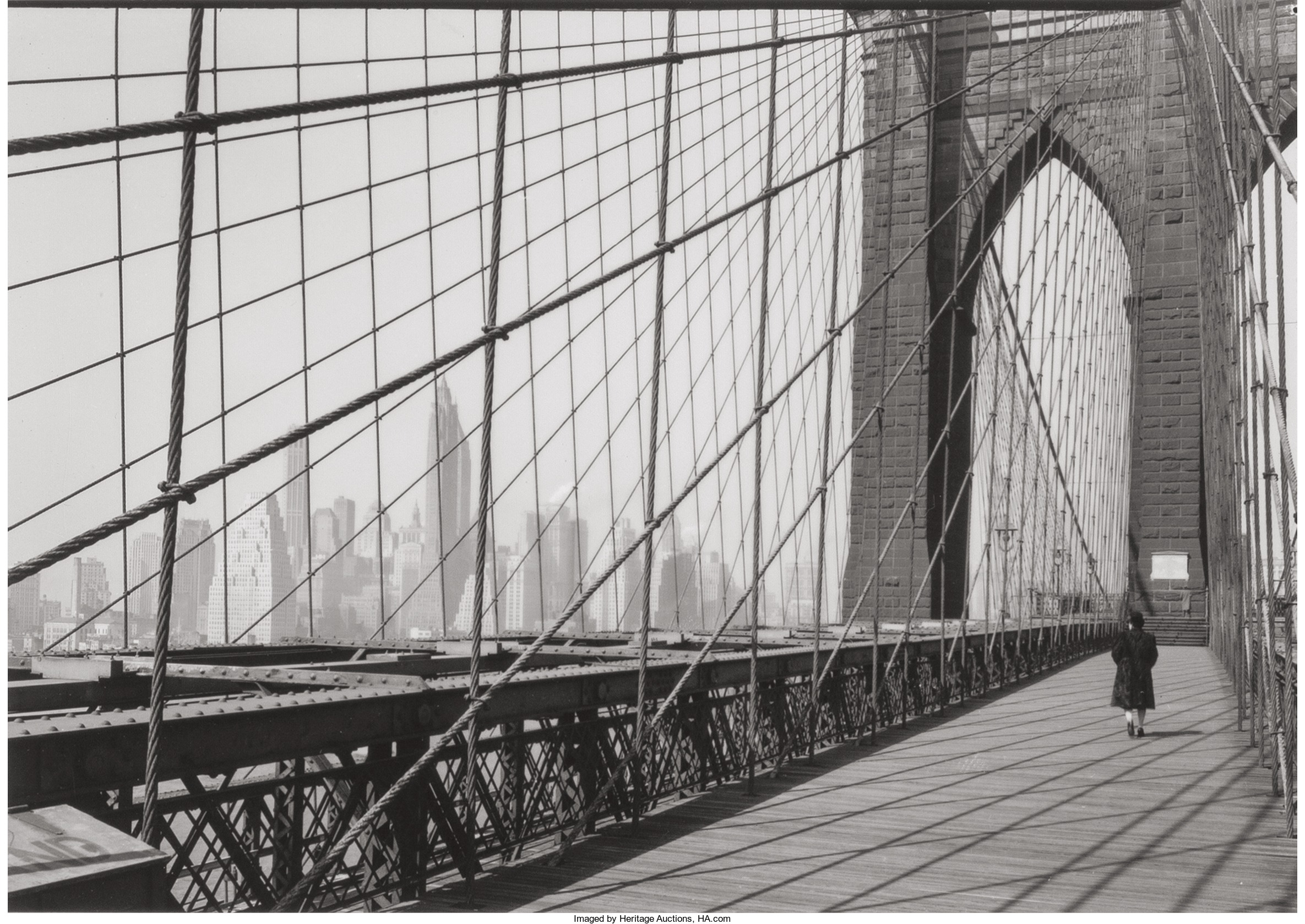

There is something appealing about bridges and the Brooklyn Bridge surpasses them all. It was the biggest, most famous in the world and is an enduring testament to American ingenuity and spirit. More than a mile long and connecting Manhattan and Brooklyn by spanning the East River, its enormous granite towers loomed higher than anything ever seen. Higher than any building in New York or any structure on the North American continent, it became “The Thing” every visitor to NYC craved to see and a spectacle that awed tens of millions of immigrants.

Its designer, the brilliant John Augustus Roebling, promised – with characteristic immodesty – a stunning example of great engineering combined with unique artistic visual effects. Roebling had perfected the suspension form, with bridges at Niagara, Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, and the masterpiece over the East River was to be his crowning project. Tragically, he died in 1869 before the design was complete after a freak accident crushed his toes. The amputation that followed exposed him to tetanus; another vivid example of the hazards associated with non-sterile medical practices combined with the absence of anti-bacterial drugs.

Fortunately, his son, Washington Roebling, possibly the only other person qualified to take over, was available. A Civil War veteran, he was admired for his intelligence, decisiveness and courage … qualities essential to surmounting the many obstacles ahead. His fearless dedication exposed him to all the potential dangers involved, but he too fell victim to a physical ailment that curtailed his involvement. He spent the next 14 years in confinement, watching over the work with a telescope from a window in his house.

Again, fortune prevailed as his wife, Emily Warren Roebling, visited the site several times a day to appraise the progress firsthand. She also handled the press and the project trustees, gradually becoming familiar with every detail and a remarkable asset for her husband. But because he was never seen, rumors were rampant that Washington had lost his mind and that this daring, great project was actually being run by a woman! In fact, when the towers were complete and the long span was safe, the first horse and carriage to cross included Emily Roebling carrying a rooster as a symbol of triumph.

The bridge opened on May 24, 1883, and President Chester Arthur rode in one of the 1,800 vehicles that crossed it, along with 130,000 people. The fireworks celebration that night was the most spectacular ever seen. The only major incident came six days later when a woman fell down some wooden stairs, causing a stampede that resulted in at least 12 deaths. P.T. Barnum tried to get permission to restore confidence in the bridge’s safety, but it would take a year until May 17, 1884, before he led his famous Jumbo and 21 other elephants across the bridge in a grand show of stability.

Initially, the bridge was designed to provide more space for Manhattan by boosting access to nearby Brooklyn. No one had thought about growing cities up instead of expanding out. As the amazing NYC skyline reminds us today, that was soon to change.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].