By Jim O’Neal

After the Civil War, thousands of farmers found themselves mired in a European style of serfdom. By 1883, they were trapped by the monopolistic pricing of both merchants and the railroads, which consumed virtually all their profits. To make their dilemma even worse, the federal government had returned to the gold standard after the war ended and demands of Wall Street drained money from rural banks to the point that entire regions were essentially broke.

The poor farmer was in the classic squeeze where the harder they worked and the more they produced the less they had. An early attempt to break the conundrum was to band together in what was called the Farmers’ Alliance, which began in Lampasas, Texas, in 1877. The Alliance quickly spread to Kansas, but within six years it was a failed effort since market forces were simply too strong for such an amateurish effort born out of desperation and lacking any real leverage or political power.

Voila! Enter the first in a long string of populists, a 36-year-old former tenant farmer from Mississippi: S.O. Daws. It was Daws’ goal to convert the Alliance into an overtly political organization, with its own Populist platform, formal candidates and party structure. However, his real genius lay in a dazzling oratory skill and grasp of political tactics. Daws persuaded the Alliance to appoint him “Traveling Lecturer” and he quickly started spreading the word and convincing his fellow farmers what to do.

One of his converts was a 34-year-old Tennessean named William Lamb, an undereducated (25 days of formal education) rail-splitter and farmer with an almost unsurpassed talent for organization. Together, Daws and Lamb provided the spark the Alliance had been missing. They used the sweeping executive power the farmers granted and soon had literally hundreds of thousands of new recruits in the organization. All told, they actually enlisted over 2 million people in 43 states. Populist historian Lawrence Goodwyn characterized it as the most massive organizing drive of any citizen institution in the entire 19th century in America.

But the Populists were never really about their leaders. They were about an idea, or actually many ideas … anything that might allow common men to make a living off the land while maintaining their human dignity. Generally, they were derided as nativist hicks, primarily because of later efforts. At the beginning, when they were at their best, they were staunchly anti-racist and injected a firestorm of ideas into a political system that tended to be moribund. Populist programs included a graduated income tax, the eight-hour workday, direct election of senators, citizen referendums, the secret ballot and, above all, regulation of agricultural markets to ensure farmers a decent return for their labor.

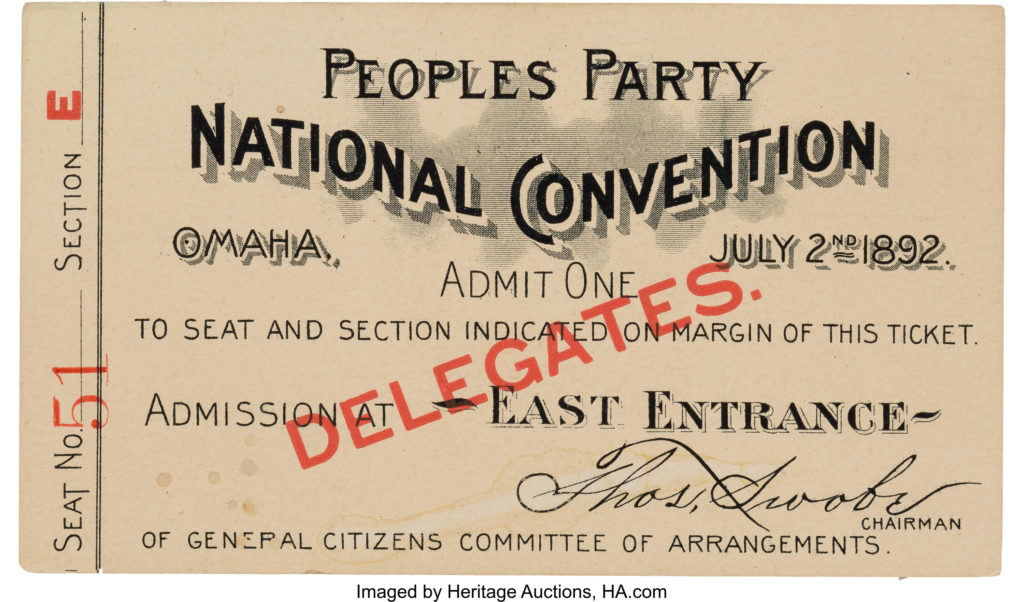

Time and fate worked against the Populists as America became increasingly industrialized with the lure of urbanization. After running their candidate for president in 1892, James B. Weaver of Iowa, the Populist Party (also known as the People’s Party or simply the Populists) folded themselves into William Jennings Bryan’s silver wing of the Democratic Party. Naturally, many of their ideas were also subsumed into other progressive political movements. One example is Sam Ealy Johnson (LBJ’s father), who served in the Texas House of Representatives from 1905-1924, and who said: “The job of government is to help people who are caught in the tentacles of circumstances.” Clearly a Populist inspiration.

Obviously, FDR incorporated many of the same concepts into his New Deal programs that helped during the Great Depression. The real Populist legacy lives on in a thousand other ways yet today, but these were people capable of standing in the hot sun for hours, and listening to speeches about obscure and esoteric subjects while working their way to a better life for all. This is how a democratic culture is created and we need to ensure it doesn’t get diluted by ruinous socialist beliefs that have failed every time well-intentioned people go too far.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].