By Jim O’Neal

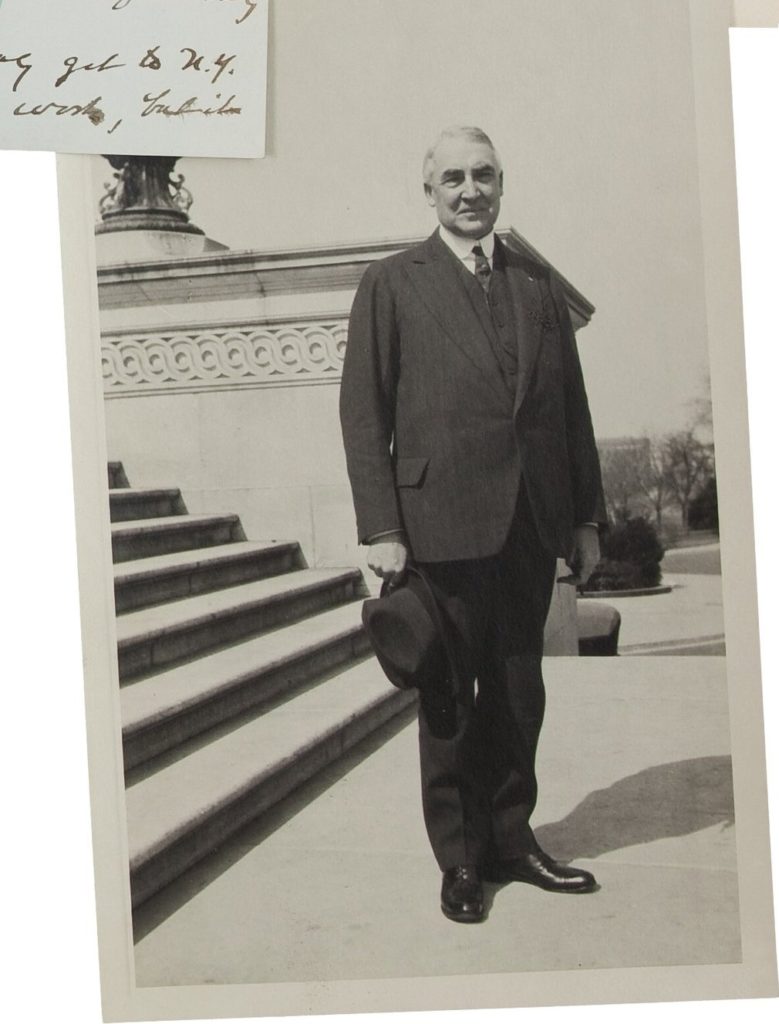

The news of President Warren G. Harding’s death astonished the American people. Telephone and telegraph lines stayed busy between San Francisco and Washington. A special railroad car, “The Superb,” was outfitted as a hearse. Twenty-four hours after the president died, the train left San Francisco, pulling the lighted car with its flag-draped coffin, honor guard and banks of flowers.

“The spectacle of the funeral train traversing the entire breadth of the United States,” observed The Washington Post, “is not to be forgotten.”

News of Harding’s death arrived at the White House by telephone. Irwin “Ike” Hoover, the White House Chief Usher, had been trying to keep a diary, but he never seemed to make a record of important things. “President dies” was all he recorded that day. In fact, his book was merely a series of blank pages for all the early days of August 1923. Hoover’s job was to run the White House, not record history. He quickly set to work hanging crepe over the mirrors of the East Room. Then the shades were drawn and the house was closed to the public.

Later, the book 42 Years in the White House chronicled Hoover’s service, which started in 1891 (when he installed the first electrical wiring in the White House) and continued through nine presidents, starting with Benjamin Harrison and ending with Herbert Hoover. He died in 1933 and President Franklin D. Roosevelt offered the White House for his funeral. Oh, the tales that probably didn’t get recorded.

Harding’s funeral train pulled into Union Station on Aug. 7. It had held the world transfixed during its five-day trip across the nation. An honor guard transported the coffin from the train with great ceremony and Harding’s body was placed in the East Room. The funeral was held in the Capitol with his Cabinet, Congress and a large group of invited dignitaries.

Florence Harding had a quiet dinner with Calvin Coolidge and his family, and would remain in the White House for five busy days. She had a fire built in the fireplace in the Treaty Room and then methodically started burning the presidential papers she determined should not survive. Then she had all the remaining papers packed into boxes and removed to a nearby friend’s house. Then she resumed the burning more slowly in small fires on the lawn.

President Harding’s secretary, George Christian, stood by helplessly during this process, until he found some papers undisturbed in the Oval Office and hid them in the pantry on the first floor. They remained there, apparently forgotten, until after Mrs. Harding’s death. Then they were given to the Library of Congress. No other papers of President Harding are known to have survived the purge of his records.

Later, the “Harding Scandals” would offer one possible reason for this unusual situation.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].