By Jim O’Neal

George Washington was the only United States president who lived his entire life in the 18th century (1732-1799). However, every early vice president – from John Adams on – spent a significant part of their lives in the 19th century. Of the Founding Fathers, Benjamin Franklin (often considered the “grandfather” of the group), was born in 1706 and died in 1790 – nine years earlier than even Washington. In reality, he was actually a member of the previous generation and spent virtually all of his life as a loyal British subject.

As a result, Franklin didn’t have an opportunity to observe the nation he helped create as it struggled to function smoothly. Many were determined not to simply replicate the English monarchy, but to establish a more perfect union for the common man to prosper (women, slaves and non-property owners would have to wait). Franklin was also a man of vast contradictions. He was really a most reluctant revolutionary and discretely wished to preserve the traditions of the British Empire he had grown so familiar with. He secretly mourned the final break, even as he helped lead the fight for America’s independence.

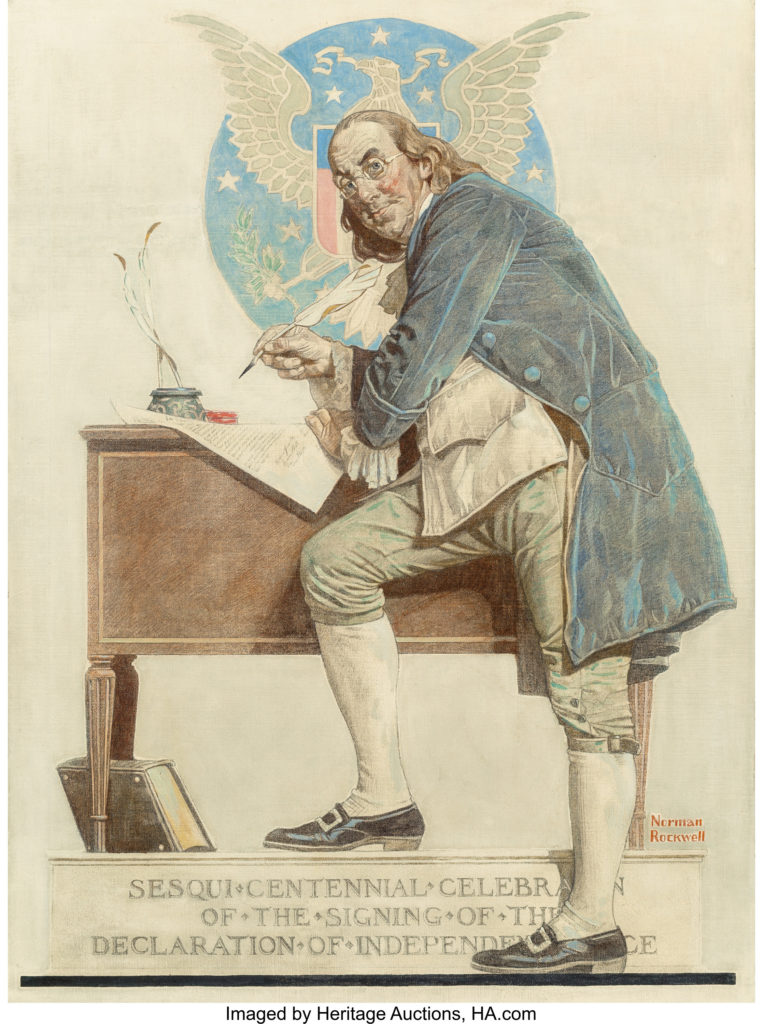

Even while signing the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, like many other loyalists, he hoped for some sort of reconciliation, a hopeless cause after so many careless British transgressions.

Fortunately, we have a rich history of this remarkable man’s life since he was such a prolific writer and his correspondence was greatly admired, and thus preserved by those lucky enough to receive it. Additionally, his scientific papers were highly respected and covered a vast breadth of topics that generated interest by the brightest minds in the Western world. He knew most of them personally on a first-name basis due to the many years he lived in France and England while traveling the European continent. Government files are replete with the many letters exchanged with heads of state.

Despite his passion for science, Franklin viewed his breakthrough experiments as secondary to his civic duties. He became wealthy as a young man and this provided the freedom to travel and assume important government assignments. Somehow, he was also able to maintain a pleasant marriage despite his extended absences, some for as long 10 years. He rather quickly developed a reputation as a “ladies’ man” and his social life flourished at the highest levels of society.

Some historians consider him the best-known celebrity of the 18th century. Even today, we still see his portrait daily on our $100 bills – colloquially known as “Benjamins” – and earlier on common 50-cent pieces and various denominations of postage stamps. Oddly, he is probably better known today by people of all ages than those 200 years ago. That is true stardom that very few manage to attain.

Every student in America generally knows something about Franklin flying a kite in a thunderstorm. They may not know that he proved the clouds were electrified and that lightning is a form of electricity. Or that Franklin’s work inspired Joseph Priestley to publish a comprehensive work on The History and Present State of Electricity in 1767. And it would be exceedingly rare if they knew the prestigious Royal Society honored him with its first Copley Medal for the advancement of scientific knowledge. But they do know Franklin from any picture.

Others may know of his connection to the post office, unaware that the U.S. postal system was established on July 26, 1775, by the Second Continental Congress when virtually all the mail was sent to Europe, not to themselves. There were no post offices in the Colonies and bars and taverns filled that role nicely. Today, there are 40,000 of them handling 175 billion pieces (six per second) and they have an arrangement with Amazon to deliver their packages, even on Sundays. Mr. Franklin helped create this behemoth as the first Postmaster General.

Franklin was also a racist in an era when the word didn’t even exist. He finally freed his house slaves and later became a staunch opponent of slavery, even sponsoring legislation. But he literally envisioned a White America, most especially for the Western development of the country. He was alarmed about German immigrants flooding Philadelphia and wrote passionately about their not learning English or assimilating into society. He was convinced it would be better if blacks stayed in Africa. His dream was to replicate England since the new nation had so much more room for expansion than that tiny island across the Atlantic. But we are here to examine the extraordinary mind and curiosity that led to so many successful experiments. Franklin always bemoaned the fact that he had been born too early and dreamed about all the new wonderful things that would be 300 years in the future.

Dear Ben, you just wouldn’t believe it!

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].