By Jim O’Neal

On his final day in office, President James Polk wrote in his diary: “Closed my official term of President of the United States at 6am this morning.”

Later, after one last stroll through the silent White House, he penned a short addendum: “I feel exceedingly relieved that I am now free from all public cares. I am sure that I will be a happier man in my retirement than I have been for 4 years ….” He died 103 days later, the shortest retirement in presidential history and the first president survived by his mother. His wife Sarah (always clad only in black) lived for 42 more lonely years.

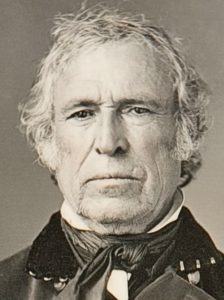

The Washington, D.C., that greeted his successor, General Zachary Taylor (“Old Rough and Ready”), still looked “unfinished” – even after 50 years of planning and development. The Mall was merely a grassy field where cows and sheep peacefully grazed. The many plans developed in the 1840s were disparate projects. Importantly, the marshy expanse south of the White House was suspected of emitting unhealthy vapors that were especially notable in the hot summers. Cholera was the most feared disease and it was prevalent until November each year when the first frost appeared.

Naturally, the affluent left the Capitol for the entire summer. Since the Polks had insisted on remaining, there was a widespread belief that his death so soon after departing was directly linked to spending the presidential summers in the White House. The theory grew even stronger when Commissioner of Public Buildings Charles Douglas proposed to regrade the sloping fields into handsome terraces under the guise of “ornamental improvement.” Insiders knew the real motive was actually drainage and sanitation to eliminate the foul air that hung ominously around the White House. (It’s not clear if Donald Trump’s campaign promise to “drain the swamp” was another effort or a political metaphor.)

President Taylor was inaugurated with a predictable storm of jubilation since his name was a household word. After a 40-year career in the military (1808-1848), he had the distinction of serving in four difference wars: War of 1812, Black Hawk War (1832), Second Seminole War (1835-1842), and the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). By 1847, Taylormania broke out and his picture was everywhere … on ice carts, tall boards, fish stands, butcher stalls, cigar boxes and so on. After four years under the dour Polk, the public was ready to once again idolize a war hero with impeccable integrity and a promise to staff his Cabinet with the most experienced men in the country.

Alas, a short two years later, on July 9, 1850, President Taylor became the second president to die in office (William Henry Harrison lasted 31 days). On July 4, after too long in the hot sun listening to ponderous orations and too much ice water to cool off, he returned to the White House. It was there that he gorged on copious quantities of cherries, slathered with cream and sugar. After dinner, he developed severe stomach cramps and then the doctors took over and finished him off with calomel opium, quinine and, lastly, raising blisters and drawing blood. He survived this for several days and the official cause of death was cholera morbus, a gastrointestinal illness common in Washington where poor sanitation made it risky to eat raw fruit and fresh dairy products in the summer.

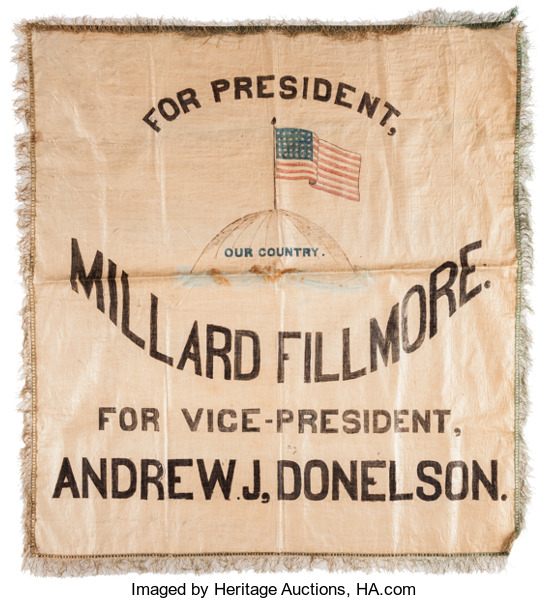

Vice President Millard Fillmore took the oath of office and spent the rest of the summer trying to catch up. Taylor had spent little time with his VP and then the entire Cabinet submitted their resignations over the next few days, which Fillmore cheerfully accepted. He immediately appointed a new Cabinet featuring the great Daniel Webster as Secretary of State. On Sept. 9, 1850, he signed a bill admitting California as the 31st state and as “a free state.” This was the first link in a chain that became the Compromise of 1850.

The Constitutional Congress did not permit the words “slave” or “slavery” since James Madison thought it was wrong to admit in the Constitution the idea that men could be considered property. In order to get enough states to approve it, it also prohibited Congress from passing any laws blocking it for 20 years (1808), by which it was assumed slavery would have long been abandoned for economic reasons. However, cotton production flourished after the invention of the cotton gin and on Jan. 1, 1808, President Thomas Jefferson signed into law that “Congress will have the power to exterminate slavery from our borders.”

This explains why controlling Congress was key to controlling slavery, so all the emphasis turned to maintaining a delicate balance whenever a new state was to be admitted … as either “free” or “slave.” Fillmore thus became the first of three presidents – including Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan – who worked hard to maintain harmony. However, with the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, it was clear what would happen … and all the Southern states started moving to the exit signs.

A true Civil War was now the only option to permanently resolving the slavery dilemma and it came with an enormous loss of life, property and a culture that we still struggle with yet today. That dammed cotton gin!

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].