By Jim O’Neal

Several readers have asked how the Civil War was waged for so long with both sides short of the resources needed to wage war. Here is a short example of how it was possible.

Still desperate for money, Confederate States Treasury Secretary Christopher Memminger proved to be creative. After Fort Sumter, he proposed a series of 12.5 percent duties on coal, lumber, cheese, paper and even iron – despite the military need for wood and iron for railroads. He came up $25 million short because of the blockade, especially in New Orleans. But after the surprise Confederate victory at Bull Run, he went back to the Confederate States Congress and asked them to impose taxes on real estate, slaves and any other personal property, since these assets were valued at almost $6 billion. Farmers effectively killed this effort since it hit them disproportionately. The Treasury then resorted to a “war tax,” but it was a real dud.

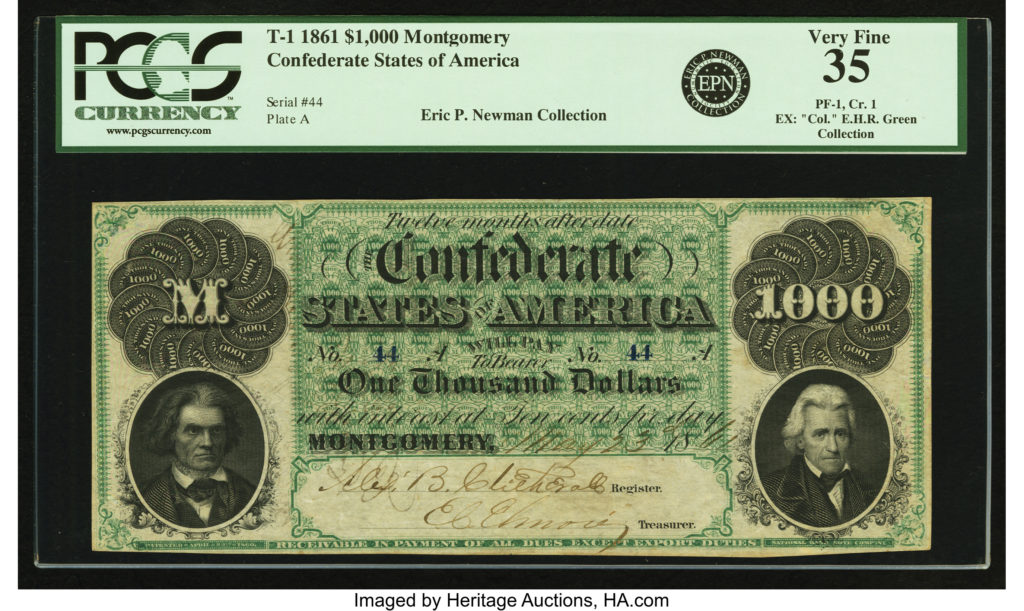

So, the only way out was to turn to the old tactic of printing money … short-term notes, longer-term bonds. The notes were, in reality, simply “script” forced on soldiers, retailers, suppliers and anyone else the Confederate government owed. Predictably, Confederate currency was issued in bigger and bigger amounts and redemption dates deferred longer into the future. By the end of 1861, the total had grown from $1 million to $30 million, to $450 million in 1862, and doubling into billion territory in 1863. Gold and silver were really the only currencies of value and they were being hoarded as their value continued to grow. In a mark of futility, merchants, railroads and other businesses started issuing their own paper currency, commonly called “shinplasters” since there were basically worthless. An editor in Mississippi wrote, “Great God, what a people. 250 different sorts of shinplasters and not one dime in silver to be seen.”

As the money devalued, a “greenback” was worth four Confederate dollars, a gold dollar went from three to 20, and in the final years, the exchange rate was 1,000 to one … if it was available. For consumers, inflation meant ruinous prices … coffee four times in 1861, 25 times higher a year later, then 80 times higher in 1863, and by the end of 1864, 125 times more expensive. The Daily Telegraph in Macon, Ga., said: “An oak leaf will be worth just as much as the promise of the Confederate Treasury to pay one dollar.”

By the end of the war, the South was a land of blackened cities, destroyed factories, destitute families and rotting wharves. Twenty-five percent of military-age men were dead, 40 percent of livestock and thousands of miles of railroads ruined, and its system of slave labor, the foundation of its economy, was gone. Sixty-five percent of the South’s wealth simply vanished. The South became a place of death, destruction, debt, ruin and humiliation. Recovery would take 100 years.

A good analogy was Germany in the 1920s when they tried to print money until a loaf of bread cost a wheelbarrow of money. It continued to escalate until the paper was worth more than the finished printed money.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].