By Jim O’Neal

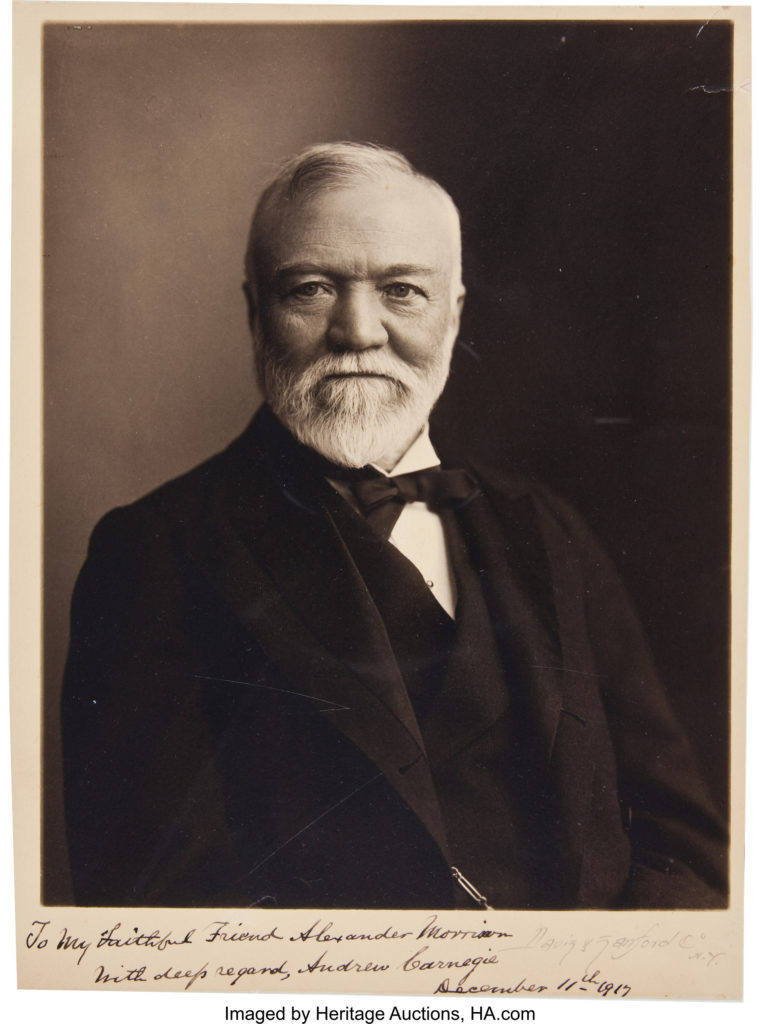

Jeff Bezos of Amazon is the world’s richest man, with an estimated net worth of more than $100 billion. A hundred years ago (1916), John D. Rockefeller became America’s first billionaire, which in today’s economy would be two to three times greater than Bezos’ fortune. In the late 19th century, Andrew Carnegie coveted this crown and saw steel as his road to stardom.

In the post-Civil War era, America grew rapidly as railroads crisscrossed the country and extended their reach to all four corners. Electricity arrived to light up buildings and homes, oil supplemented kerosene and coal, iron and steel production grew as demand soared to keep up with rapid economic expansion. Occasional booms/busts occurred since the markets were unregulated and coordination was difficult.

Carnegie had led the growth in the American steel industry and his ambition to snatch Rockefeller’s crown became more acute. One of the key industry developments involved the construction of a steel bridge to connect St. Louis and East St. Louis on opposite banks of the mighty Mississippi River. The Eads Bridge, named for its designer, engineer James B. Eads, relied heavily on steel for its revolutionary design. It was set to become the first significant bridge using steel girders and a cantilever form.

A young Carnegie supplied the financing and the steel, despite skepticism over the sturdiness of the structure after it was completed. A man named John Robinson came up with a clever way to dispel any doubts. Elephants were believed to have good instincts about where they stepped, so Robinson borrowed a fully grown one from a traveling circus. On June 14, 1874, he led the beast across the length of the bridge, with crowds on both ends going wild. Later, a convoy of locomotives were driven back and forth as a further (and final) test of soundness.

On July 4, 1874, the bridge officially opened with General William Tecumseh Sherman driving the last spike as 150,000 people looked on. Demand for steel exploded, forcing Carnegie to develop creative ways to boost production. One was a modified vertical production technique that maximized factory output. But that was still not enough. It became obvious that a 12-hour, six-day workweek was needed. The only problem was that workers’ health couldn’t keep up. Carnegie hired tough managers to impose the onerous schedule and he left for Scotland to escape the critics. Later, his guilty conscience led him to an unprecedented binge of philanthropy after he sold the Carnegie Steel Company to J.P. Morgan for $480 million. It became U.S. Steel, the first billion-dollar corporation in the world.

John D. Rockefeller took an even more devious strategy to his domination of the oil-refining industry. In 1872, he formed a shell corporation: the South Improvement Company (SIC). He then struck an agreement with large railroad companies whereby they sharply raised freight rates for all oil refineries, except those in the SIC (notably Standard Oil), which received substantial rebates – up to 50 percent off crude and refined oil shipments. Then came the most deadly innovation – SIC members also received “drawbacks” on shipments made by rival refineries. So when Standard Oil made shipments from Pennsylvania to Cleveland, they received a 40-cent rebate on every barrel, plus another 40 cents for every barrel of oil shipped by every competitor!

It has been called “an instrument of competitive cruelty unparalleled in industry.” In fact, it was collusion on a scale never equaled in American history. And it was only one of several techniques employed. But it did help Mr. Rockefeller and his investors achieve a 90 percent share of the entire U.S. oil business.

All Bezos has is the internet.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].