By Jim O’Neal

In April 1983, my Frito-Lay team toured a research laboratory in Delaware to view their facilities and new product development using polypropylene in our packaging systems. At one point, the national sales manager prodded their head scientist about the possibility of speeding it up and, memorably, the reply was a curt “We don’t schedule inventions.”

At the time, it seemed like a profound statement to me, but that was before I got to know Thomas Edison via his writings and others stories about his fabled career.

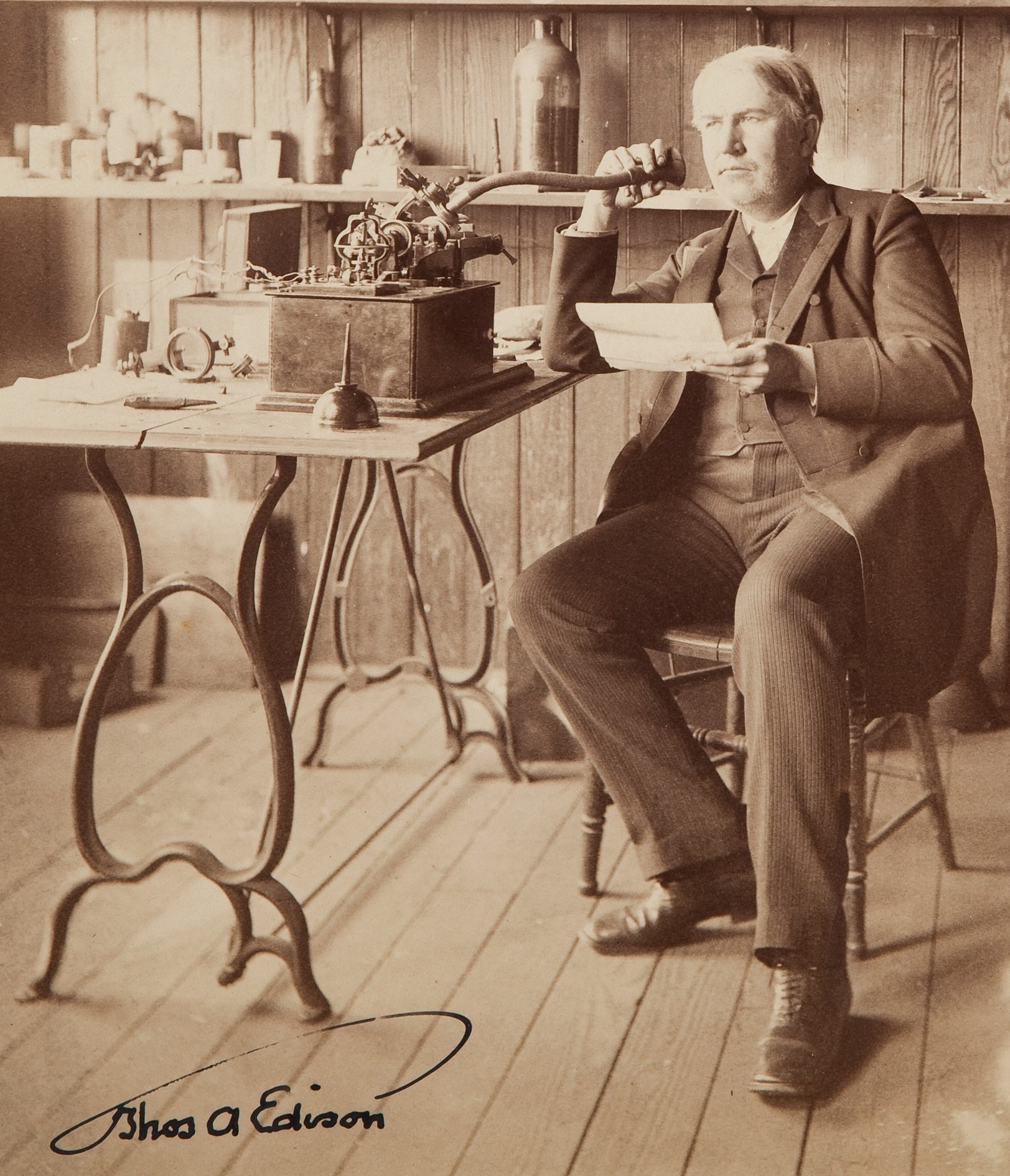

Edison’s invention factories were not torn over the merits of applied science versus basic research. They were always about applied research, but with a vengeance! “I find out what the world needs. Then I go ahead and invent it,” Edison said. And did he ever. When he was finished, he would have 1,093 patents in his own name alone, more than any other American in history.

His second patented invention, a stock market ticker, sold for $40,000 in 1869. The sale provided the money for a workshop in Newark, N.J., where he and a small group of workers produced stock tickers, ink recorders and typewriters for automatic telegraphy. In 1876, he moved the shop 12 miles to Menlo Park, where the first of the invention factories was built. The lab and workers were just a hundred yards from Edison’s home.

It was an eclectic group from all over the world: a German glass blower, an English mechanic, mathematicians, carpenters, and draftsmen. Menlo Park became the best private laboratory in the country. The atmosphere Edison created encouraged independent, creative thinking. “There ain’t no rules around here. We’re trying to accomplish something.”

He could be authoritarian and cranky, and set impossible deadlines, since he was there shoulder-to-shoulder with employees 18 hours a day for extended times. Balancing work and personal lives was not as issue; creation was. His approach to failure was the antithesis of other corporations that flourished and failed. “If I find 10,000 ways something won’t work, I haven’t failed. I now know 10,000 ways not to do it.”

The indefatigable nature of Edison and his workers was exemplified by the search for material that could make a durable filament essential to the incandescent light bulb. After trying numerous promising candidates, on Oct. 22, 1879, they tested carbonized cotton thread. It would glow for 13½ hours without bursting into flame, the common problem with all light bulbs at the time. Problem solved.

What a difference those invention factory ideas meant to our young nation: a viable incandescent light bulb, cylinder phonographs, nickel-iron-alkaline storage batteries, the electric pen for a mimeograph, the Ediphone, the Kinetoscope, etc. Edison even created inventions that improved other inventions: a simple carbon button transmitter for the mouthpiece on AGB’s telephone … eliminating the need to shout to be heard.

Edison was a charter member of that self-taught group that fervently believed that “if this doesn’t work, we’ll just try something else.” Edison may not have defined genius as 99 percent perspiration and 1 percent inspiration, but he certainly proved, without a doubt, that “Genius is hard work, stick-to-itiveness, and common sense.”

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell]

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell]