By Jim O’Neal

The 12th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was added to clear up some fuzzy rules for presidential elections that popped up in both 1796 and 1800.

In addition to requiring separate votes for president and vice president, it added procedures for the House of Representatives if no candidate received a majority of votes. The Amendment was proposed by Congress in 1803 and then ratified by the requisite three-fourths of states in June 1804. It was easier to gain consensus in those early days.

For the next 20 years, things went smoothly as Virginians continued to occupy the White House. Presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe all served two terms with no controversies, at least regarding elections.

Then came 1824.

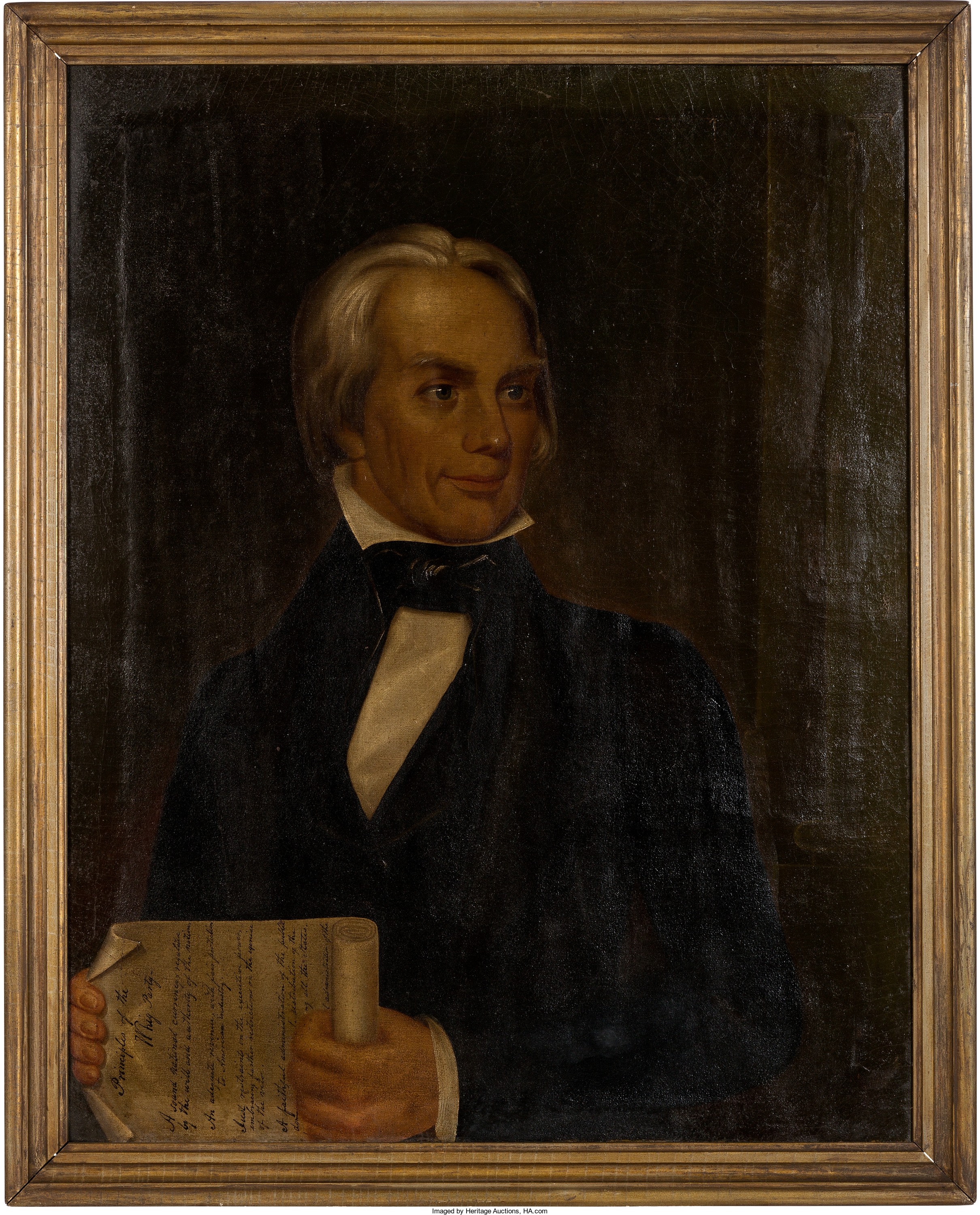

To begin, all the candidates were from the same party … the Democratic-Republican. Tennessee nominated Andrew Jackson (born in North Carolina). Kentucky chose Henry Clay. William Crawford got a nomination from Georgia, albeit from a splinter group. John C. Calhoun of South Carolina ignored state officials and nominated himself. And finally, John Quincy Adams (the eventual winner) was the conventional “favorite son” from Massachusetts following in his father’s footsteps.

Then the fun started.

First, Calhoun quickly realized he didn’t have broad support and withdrew from the presidential race. However, in a twist, he nominated himself for vice president for both Jackson and Adams, which ensured him a victory.

Crawford suffered a stroke, but remained in the race, finishing in third place. Adams finished a disappointing second in both the popular and electoral votes.

Jackson had the highest number of popular votes and ended up with the most electoral votes. However, since the votes were split four ways, he did not have a majority (more than 50 percent).

The new rules threw the election into the House of Representatives, except Clay was eliminated since only the three top electoral vote-getters were eligible for the runoff. A great controversy then erupted when Clay, who was Speaker of the House, switched Kentucky’s vote from Jackson to Adams, giving him the office … thus making Andrew Jackson the only person to win both the popular and electoral votes and lose the election.

Then John Q. Adams made Henry Clay the Secretary of State in what has become known as the infamous “corrupt bargain.” No proof has ever surfaced of this quid pro quo, but Andrew Jackson certainly believed it … so much so that he resigned from the Senate and spent the next three years plotting against Adams.

It apparently worked, since he vanquished JQA in 1828 and then won again in 1832.

If this year’s nominating process and campaigns seem to border on the bizarre, you would be right. Just consider how 1824 would compare if they had been cursed with 24/7 cable TV.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].