By Jim O’Neal

The passing of information over great distances is an ancient practice that’s used many clever techniques.

In 400 B.C., there were signal towers on the Great Wall of China; beacon lights or drumbeats also were used to relay information. By 200 B.C., the Han dynasty evolved a complex mix of lights and flags. Speed has always been a priority and took many forms, including at the U.S. Postal Service. “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds” is the unofficial motto of the Postal Service (probable source: The Persian Wars by Herodotus).

Authorized by Congress in 1792, the many forecasts of the Post Office Department’s imminent demise appear to be exaggerated. We still get incoming six days a week and a post-office driver delivered a package to my place at 8 p.m. last week … one day after I ordered it from Amazon. The post office – renamed the U.S. Postal Service in 1971 – is now running prime-time ads claiming they deliver more e-commerce packages than anyone.

Through history, postal couriers have toted a staggering volume of items, as well as a few astonishing ones. A resourceful farmer once shipped a bale of hay from Oregon to Idaho. A real coconut was sent fourth class from Miami to Detroit with the address and postage affixed to the hull. Even sections of pre-fab houses have been mailed, delivered and then assembled into full-size homes.

Accounts vary as to where the 53-cent postage was affixed to pre-schooler Charlotte May Pierstorff the day her parents mailed her to see her grandmother in Idaho. In 1914, they had discovered it was cheaper to send her by U.S. mail than the full-fare the railroad charged for children traveling alone. At 48½ pounds, little May fell within the parcel post 50-pound weight limit. She traveled in the train’s mail compartment and was safely delivered to grandma. She lived to be 78 and died in California. She’s featured in an exhibit at the Smithsonian … at the National Postal Museum.

Another cheapskate shipped an entire bank building – 80,000 bricks, all in small packages – from Salt Lake City to Vernal, Utah, in 1916. This time, the postmaster put his foot down … no more buildings! But 9,000 tons of gold bars were transferred from New York to Fort Knox in 1940-41. This time, the post office collected $1.6 million in postage and insurance. My all-time favorite was when jeweler Harry Winston donated the famous Hope Diamond to the Smithsonian in 1958. He kept costs low by sending the 45.52-carat gem in a plain brown wrapper by registered first-class mail. (Note: It arrived safely.)

The quest for speed took a quantum leap on May 24, 1844, when Samuel F.B. Morse sent the first telegraph. Standing in the chamber of the Supreme Court, Morse sent a four-word message to his assistant in Baltimore, who transmitted the message back. Members of Congress watched the demonstration with fascination. At the time, the Supreme Court was housed in the Capitol building. They finally got their own building in 1935 after heavy lobbying by Supreme Court Justice William Howard Taft.

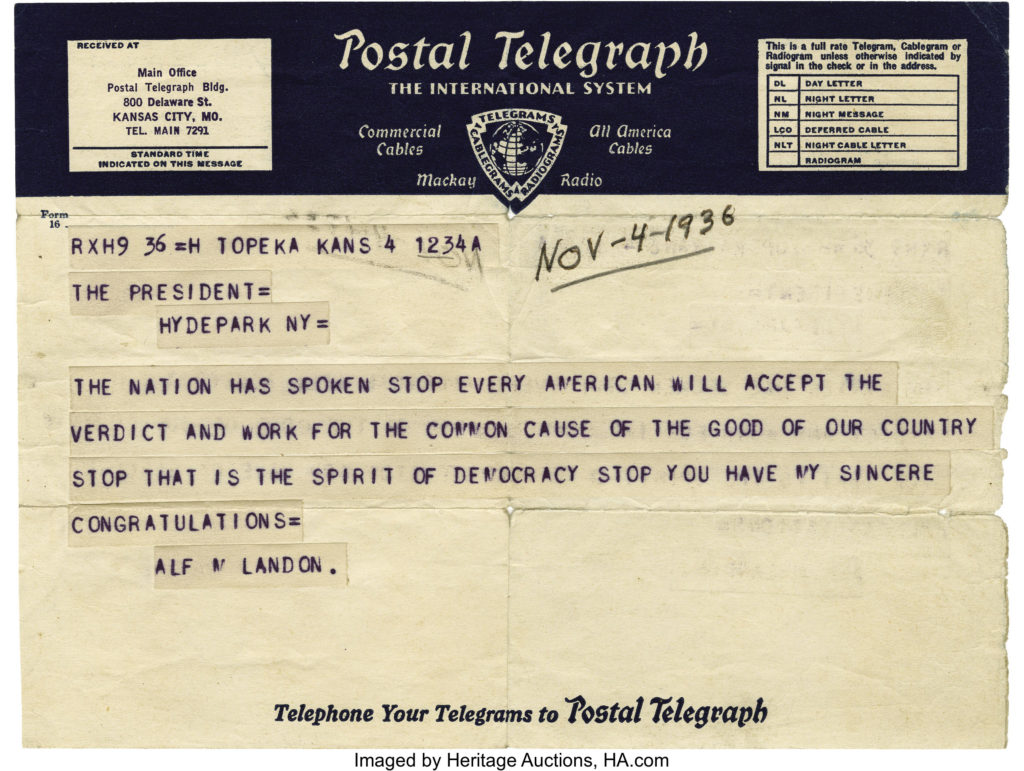

For Americans at the turn of the 20th century, seeing a telegram messenger at the door usually meant bad news. Western Union and its competitors weren’t pleased by the fact that their roles as bearers of bad news had spread. So in 1914, they started emphasizing good-news messages, sending them in bright, cheerful seasonal envelopes. Next were 25-cent fixed-text telegrams that gave senders pre-written sentiments in 50 categories, like Pep-Gram #1339: “We are behind you for victory. Bring home the Bacon!” Forgot Mother’s Day? Use #432: “Please accept my love and kisses for my father’s dearest Mrs.” Next were singing telegrams, but they became passé and in 2006, Western shut down its telegram service.

The message of that first Morse telegraph in 1844 is a question we still ask after every innovation, whether it was faxes, the internet, email or texts: “What hath God wrought?”

Perhaps next is mental telepathy. Who knows? It will be faster and awe us once again.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].