“Bring me Longstreet’s head on a platter and the war will be over.” – President Abraham Lincoln

By Jim O’Neal

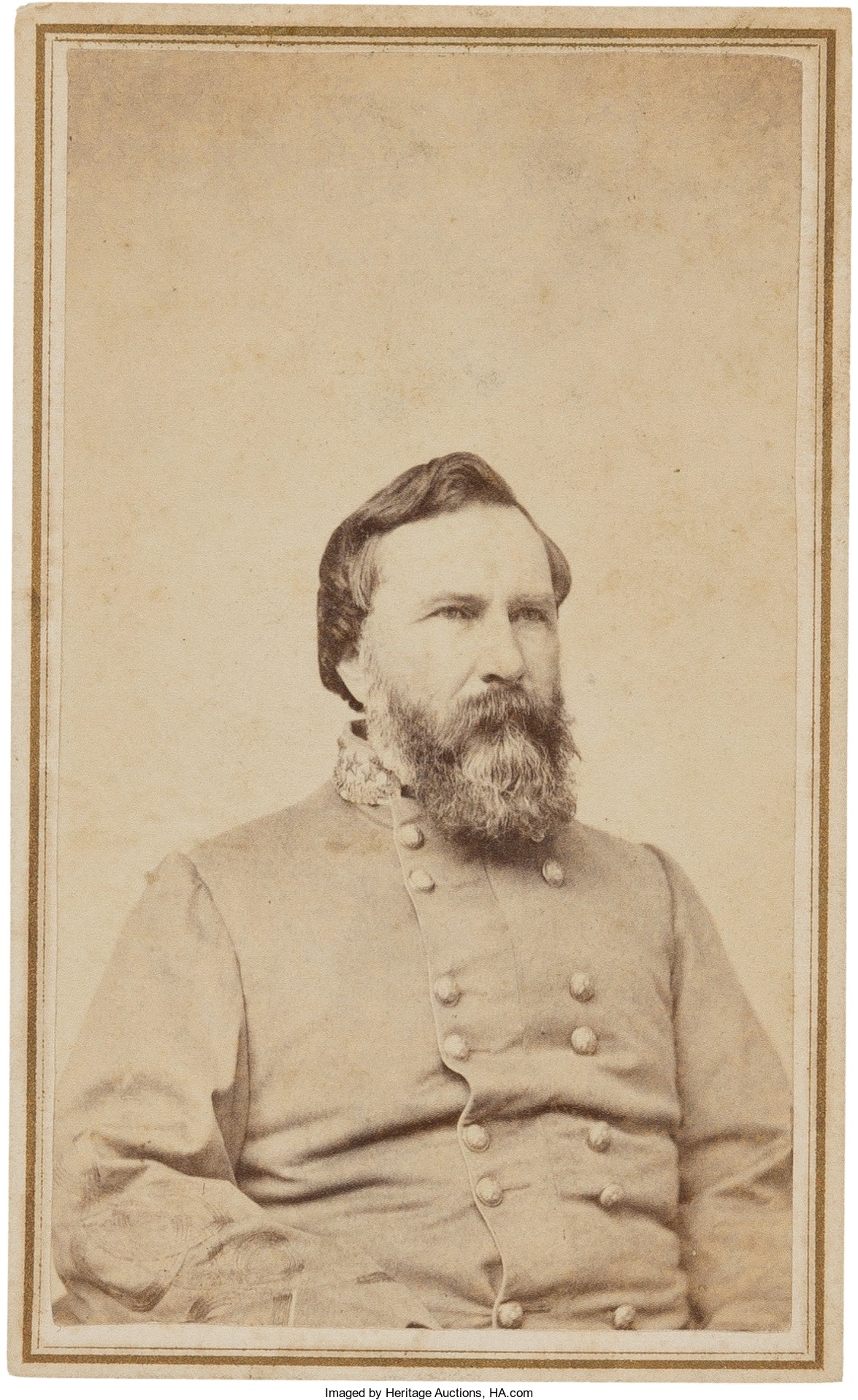

Confederate General James Longstreet (1821-1904) was born in South Carolina and his mother sent him to live with an uncle who decided his should have a military career. He received an appointment to West Point, where he underperformed academically. However, he made many lifelong friends, including future President Ulysses Grant.

Commissioned into the infantry, he served until the outbreak of the Mexican-American War. From 1847 to 1849, he served under generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott, was wounded at the Battle of Chapultepec, and finally resigned from the U.S. Army in June 1861. It was nearly a month after Fort Sumter.

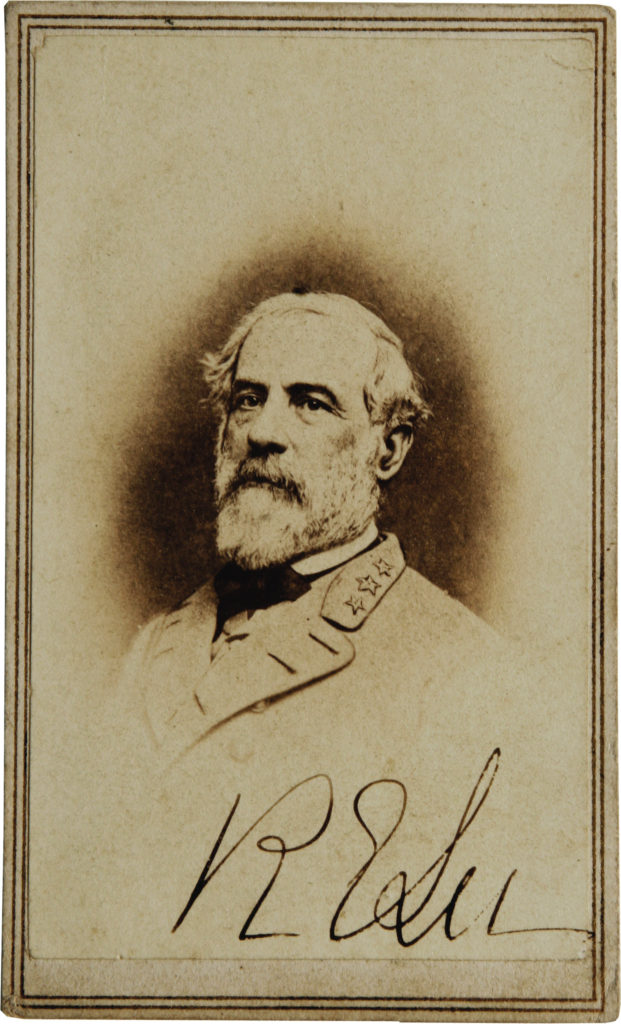

Like many of his southern colleagues, he joined the Confederacy and ended up in the Army of Northern Virginia after Robert E. Lee declined Lincoln’s offer to head up the entire Union Army. Almost inexorably, this led to the most famous battle of the Civil War. On July 1, 1863, Longstreet rode onto the battlefield of Gettysburg as infantry units were cleaning up after a decisive day-one victory. He was 42 years old.

After surveying the Federals rallying on Seminary Ridge, he lowered his field glasses, turned to General Lee and spoke – launching one of the greatest controversies of the entire Civil War. “General Lee, we could not call the enemy to position better suited to our plans… all we have to do is to flank his left…” The words either surprised or angered Lee, who pointed a fist toward the ridge beyond town: “If the enemy is there tomorrow, I will attack him!”

Despite the open disagreement, Longstreet reluctantly supervised the disastrous infantry assault known as Picket’s Charge (the high-water mark of the Confederacy) as ordered. The date was July 1863, and despite being preceded by a massive artillery bombardment, its futility was an avoidable mistake: 12,500 Confederate soldiers in nine infantry units advanced over three-quarters of a mile – charging into a withering hail of Union pure death. The staggering 50 percent casualty rate resulted in a defeat that the South never recovered from – either militarily or psychologically.

Noted historians are still debating who to blame: Lee, for overriding the advice of his most-trusted second-in-command, or Longstreet for being too slow to carry out a direct order.

Personally, I side with General George Pickett, one of three Confederate generals who led the assault under Longstreet and who was bitterly unequivocal: “That old man [Lee] destroyed my division.” His regular daily report is missing and is believed to have been intentionally destroyed, perhaps by Longstreet personally. It was now just a matter of time until the South’s war machine gradually came to a stop. The war would continue until April 1865, but the end was never again in doubt.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].