By Jim O’Neal

In 1802, a French mining engineer proposed a two-level tunnel under the English Channel to connect France and Great Britain. During the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, following the end of World War I, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George revived the idea as a means of assuring France that Great Britain was ready to help if Germany ever launched another invasion. Great Britain is the largest of the British Isles and the 9th-largest island in the world.

Although a tunnel was not available to help France when Germany invaded again in World War II, construction of the Channel Tunnel – with high-speed Eurostar train service – was finally completed in 1993. Queen Elizabeth was a passenger on the inaugural trip from London to Paris after a one-day delay due to a small, embarrassing mechanical problem. We were living in London at the time and Nancy and I were able to get reservations on the second day. We got an impressive special commemorative stamp in our U.S. passports to celebrate the occasion.

The English have a long history of special stamps, and printing and copyright laws dating to the Statute of (Queen) Anne in 1710. This act of Parliament was the first to provide copyright regulation by the government, rather than by private parties. Prior to this action, the Licensing of the Press Act of 1662 required printing presses to be approved by the e Stationers’ Company, a Royal Charter group that had a literal monopoly on the entire publishing industry.

They also had a Dr. Samuel Johnson, who published A Dictionary of the English Language in 1755. This two-volume set, and Dr. Johnson, dominated English lexicography for more than a century.

Copyright law in America dates to the Colonial period, however, the Statute of Anne did not apply for reasons that have been lost to antiquity. Instead, federal law in America was established in the late 18th century by the Copyright Act of 1790. We also did not have our own dictionary and even the spelling of words (as with their meanings) was generally left to the writer’s choice or presumed intent. Documents of that period are complicated to read and subject to varying interpretations.

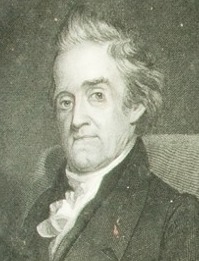

Enter Noah Webster (1755-1843), who did much more than publish a dictionary. A Yale graduate with a law degree that he never quite turned into a job, he was a co-founder of Amherst College, started America’s first daily newspaper and worked for Alexander Hamilton on the Federalist Papers. With his legal training and publishing experience, he witnessed the flaws in our system and was continually lobbying Congress to pass copyright laws specifically applicable to America.

Webster was also adamant that we needed our own dictionary, not Dr. Johnson’s, which he attacked and scorned, perhaps extreme in his criticism. “Not a single page of Johnson’s dictionary is correct!” In his mind, we needed a dictionary that was clearly American, containing words unique to the young nation’s growing vernacular. Clearly, Webster also had his own agenda to advance. In the case of “equal,” he believed the Declaration of Independence was wrong in stating that “all men are created equal.”

Webster believed in equality of opportunity, but not equality of conditions. He also disagreed with “free” – that all men were free to act according to their will. That meaning threatened government, giving people the sense they were above authority. The tension with the meaning of “free” continues, and neither Webster’s dictionary nor any other can remove it.

But there is little doubt that a comprehensive American dictionary was a critical issue that had to be resolved as our society continued to grow and expand beyond the reach of English dogma.

Noah Webster thought an American dictionary would take him three to five years to complete and he bravely stated, “I ask no favors, the undertaking is Herculean, but it is of far less consequence to me than to my country…”

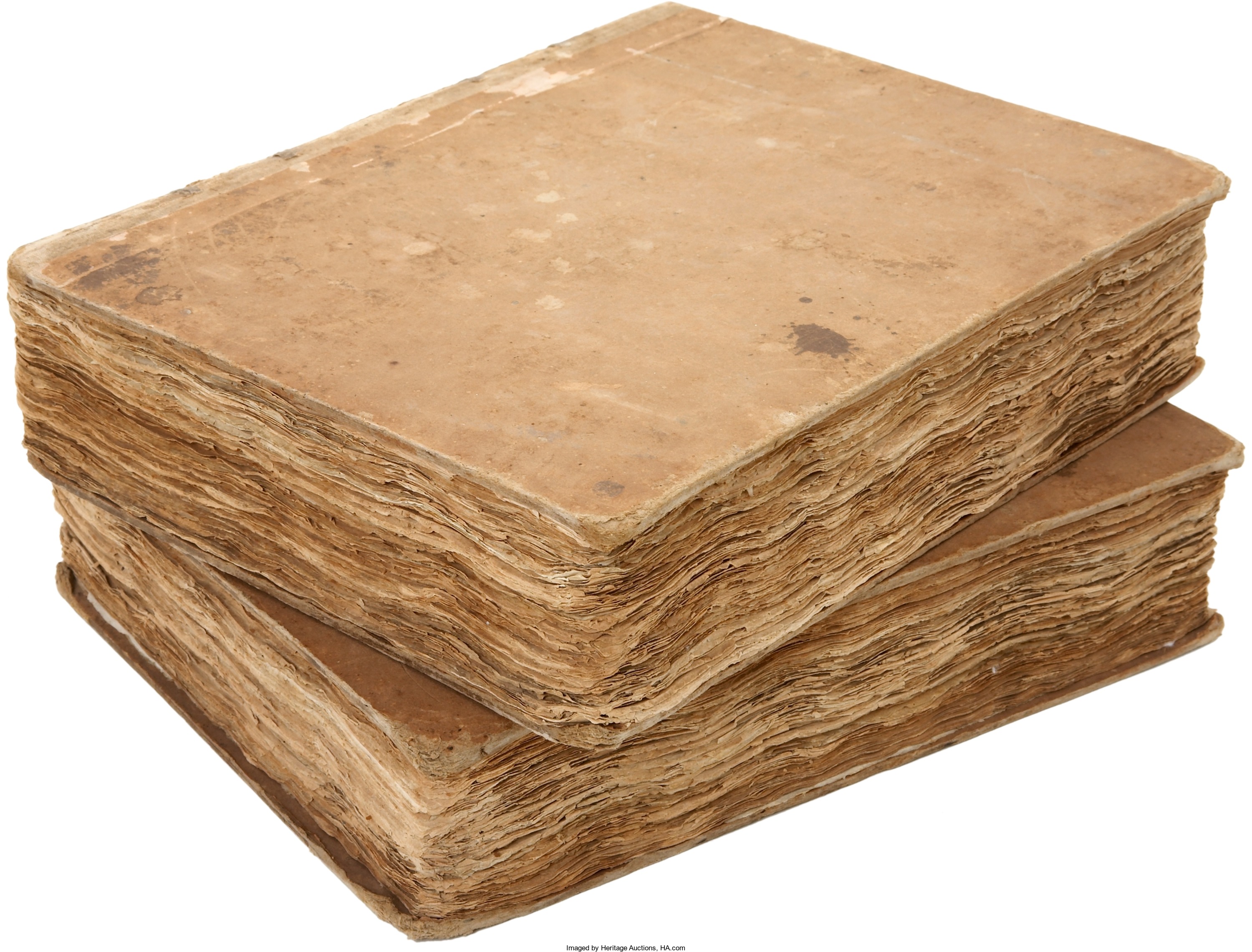

To prepare himself, he restudied his college Greek, Latin and Hebrew, perfected his French and German, then studied Danish, Anglo-Saxon, Welsh, Old Irish, Persian and seven Asiatic and Assyrian-based languages. His American Dictionary of the English Language had two volumes, 800 pages each, and sold for $20 in 1828, the year it was published. It had taken him nearly 20 years to complete.

Along the way to a common language, with common pronunciation, he included spelling books and improved teaching methods for Americans of all ages. Webster’s lasting place in the nation’s history derives from his conviction in the power of language and the necessity of fully understanding the language to exercise its power.

That conviction produced the final volume of independence from England.

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].