By Jim O’Neal

Among the towering figures of the Civil War, none is more enigmatic than General William Tecumseh Sherman.

Widely denounced as ruthlessly destructive for his infamous March to the Sea across Georgia, Sherman was a brilliant commander who helped bring the bloody war to a decisive end. His legacy of “total war” against anyone and everyone (even unarmed civilians) has haunted many Americans and military leaders. It has no parallel in U.S. military history in terms of ferocity or effectiveness.

Sherman (1820-1891) was massively paranoid due to a catastrophic event when he was 9 years old. His father, apparently very successful, suddenly went into bankruptcy and then died … leaving the family penniless and in chaos. His decision to do whatever necessary to restore order and harmony to the Union was rooted in his compulsion for normalcy.

Psychobabble aside, I tend to agree with the following: “The historians of the future will note his shortcomings. Not captiously, but in the kind spirit of impartial justice he will set them down to draw the perfect balance of his character. Let him deduct them from the qualities that mark his distinction, and we shall still see William Tecumseh Sherman looming up a superb and colossal figure in the generation in which he lived,” said General F.C. Winkler, addressing the Army of the Cumberland in the year Sherman died.

Edwin McMasters Stanton (1814-69) became Attorney General for President James Buchanan the day Major Robert Anderson moved his federal troops to Fort Sumter, S.C. This action was viewed as a quasi act-of-war and South Carolina issued an “ordinance of secession.” Later, Stanton would become Abraham Lincoln’s War Secretary and General-in-Chief, replacing General George McClellan due to “inaction.” After Lincoln’s assassination, he became the temporary de facto head of the government as Andrew Johnson was paralyzed in a state of inaction and Congress was not in session.

A man of action, Stanton mobilized the hunt for John Wilkes Booth and all suspected conspirators. All but three were hanged after a swift military tribunal found them guilty. The Stanton role was played by Kevin Kline in the 2010 movie The Conspirator, directed by Robert Redford. Robin Wright played Mary Surratt, the first woman executed by the United States. After the trial, Stanton had a contentious role in President Johnson’s Cabinet, despite their intense mutual dislike.

Johnson (1808-1875) was the only member of the U.S. Senate from a seceding state (Tennessee) to remain loyal to the Union. Hoping to make an example to undermine the Confederacy, Lincoln designated him a brigadier general of volunteers and appointed him military governor of the state with instructions to form a government and return to the Union. The best Johnson could do was declare himself the leading Unionist of the South. Lincoln was expecting a difficult re-election in 1864 and Johnson was selected as vice president in the hope he could attract Southern Democratic votes. They were nominated in June and elected in November. Johnson botched his inauguration by getting drunk; his oath of office was a rambling, incoherent speech. It was so humiliating that he left town for a week. Upon his discreet return, accounts described him as the “invisible man.” Six short weeks later, he would be president of the United States.

The lives of these three men would become forever intertwined in a fascinating series of events.

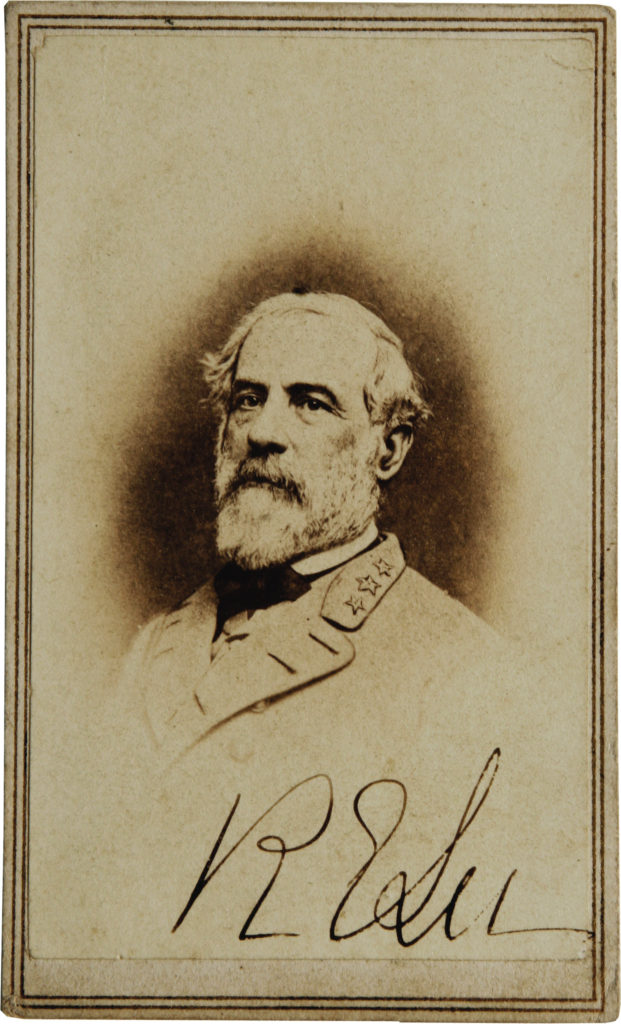

On April 9, 1865, at the Appomattox Court House, Robert E. Lee (1807-1870) surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to General Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885), who accepted the surrender under terms that were considered generous. President Lincoln accepted them since he was still apprehensive about the rest of the Southern troops.

Three Confederate generals – Joe Johnston, Edmund Kirby Smith and Nathan Bedford Forrest – were still on the loose. Lincoln and Grant feared they would form guerilla units. The war could then theoretically last several more years.

However, after Lincoln’s assassination on April 15, Johnston followed Lee’s action and surrendered his troops to General Sherman. Their first meeting was similar to Grant/Lee, except without aides and note-takers (and the eyes of history). Sherman offered to accept Johnston’s surrender on the same terms as those give to Lee. Surprisingly, Johnston demurred and countered with a stunning proposal to make it a “universal surrender” – thereby surrendering all Southern forces to the Rio Grande. In short, it would end the war once and for all.

When Sherman agreed and sent it forward, President Johnson and the entire Cabinet were furious. They suspected Sherman of a conspiracy to take over the entire country or, at a minimum, position himself for the 1868 presidential election. It took Grant 10 days of diplomacy to settle the issue, but exposed a deep rift between President Johnson and Secretary Stanton.

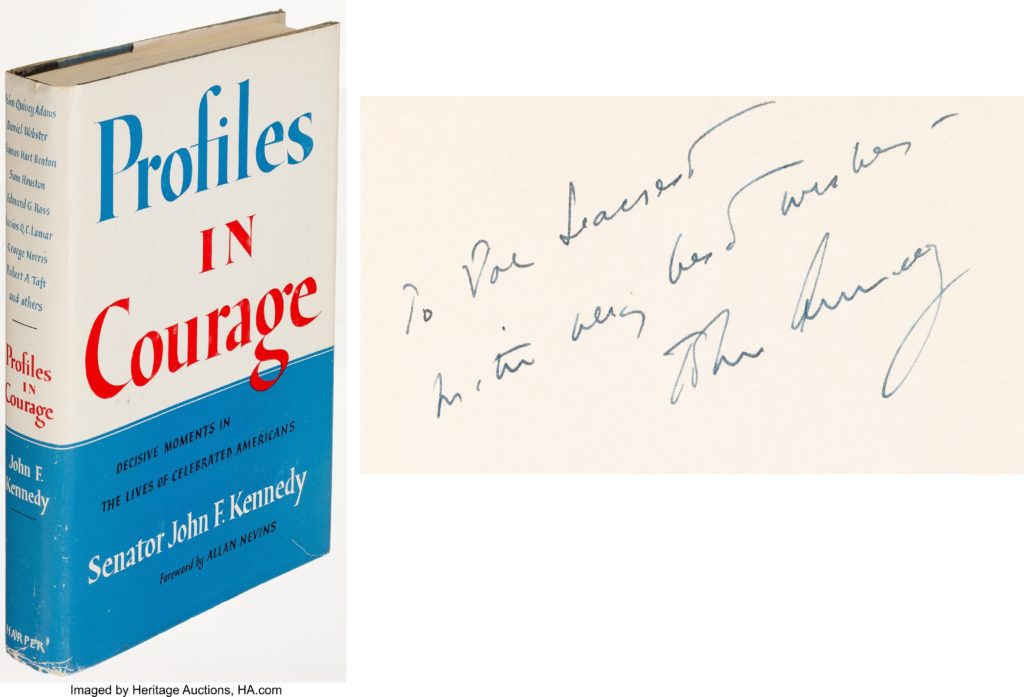

In the end, when Johnson tried to fire Stanton, the Republican Congress impeached the president for “high crimes and misdemeanors.” He was famously acquitted by one vote (twice) by Senator Edmund G. Ross of Kansas. Interestingly, Ross was among the eight men profiled in the 1957 Pulitzer Prize-winning book Profiles in Courage “by” John F. Kennedy.

Critics have claimed Ross was bribed for his vote to acquit … and that Kennedy’s speechwriter and close adviser Ted Sorensen had ghostwritten the JFK book. Even Eleanor Roosevelt weighed in, famously quipping, “I wish that Kennedy had a little less profile and more courage.”

Perhaps Henry Ford was right. History is bunk!

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].