By Jim O’Neal

Whenever the topic of “favorite author” is inevitably raised, I quickly steer the conversation to two categories. First is non-fiction, since it gives me an opportunity to nominate Shelby Foote for my all-time favorite subject of the Civil War. Secondly, I suggest that fiction favorites be limited to only writers born in the great state of Mississippi.

Shelby Dade Foote Jr. (1916-2005) spent over 20 years working on his masterpiece The Civil War: A Narrative, a three-volume, 3,000-page work that captivated me. However, like many others, it wasn’t until filmmaker Ken Burns aired his PBS documentary in 1990 that I became aware of just how much I truly appreciated it. In the first hour of the 12-hour series, Foote appeared in 90 segments. His sagacious comments and distinctive Southern drawl added a remarkable degree of authenticity to an otherwise only great production.

Legend has it that paperback sales of Foote’s book jumped to 1,000 per day and ended up selling over 400,000 mores copies – all as a result of his newfound celebrity. He reportedly remarked to Burns: “You have made me a millionaire.” A few critics complained that Foote had a Southern bias and cited a passage where he stated that Abraham Lincoln and Confederate Army general Nathan Bedford Forrest were the two smartest men in the entire war and tried to point out a few weaknesses of Forrest when they really objected to simply pairing him with the revered Lincoln.

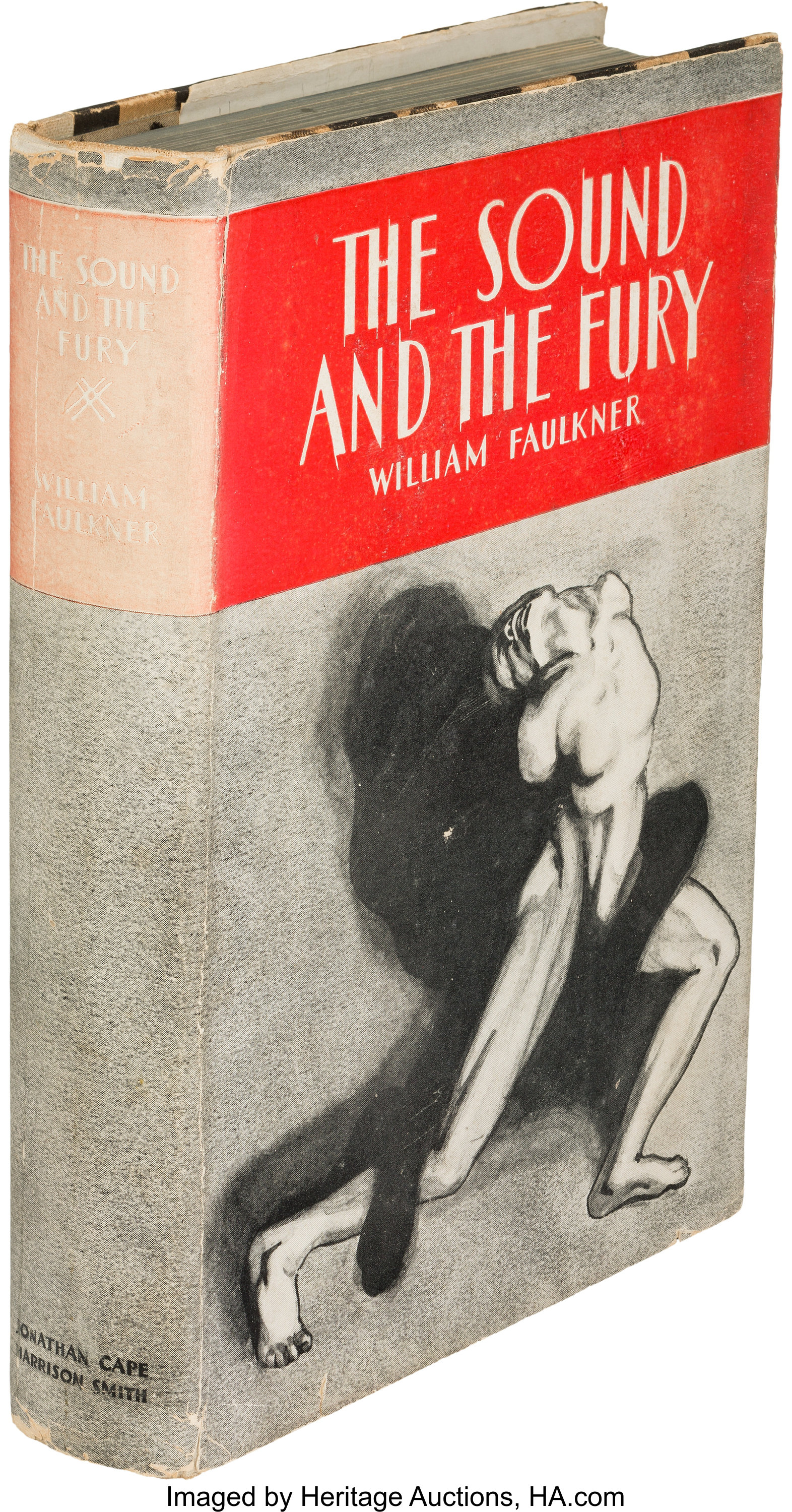

As for fiction writers born in Mississippi, there are a lot more to choose from than you might expect. Consider Eudora Welty (The Optimist’s Daughter), Willie Morris (North Toward Home) and William Faulkner (As I Lay Dying), to name a few.

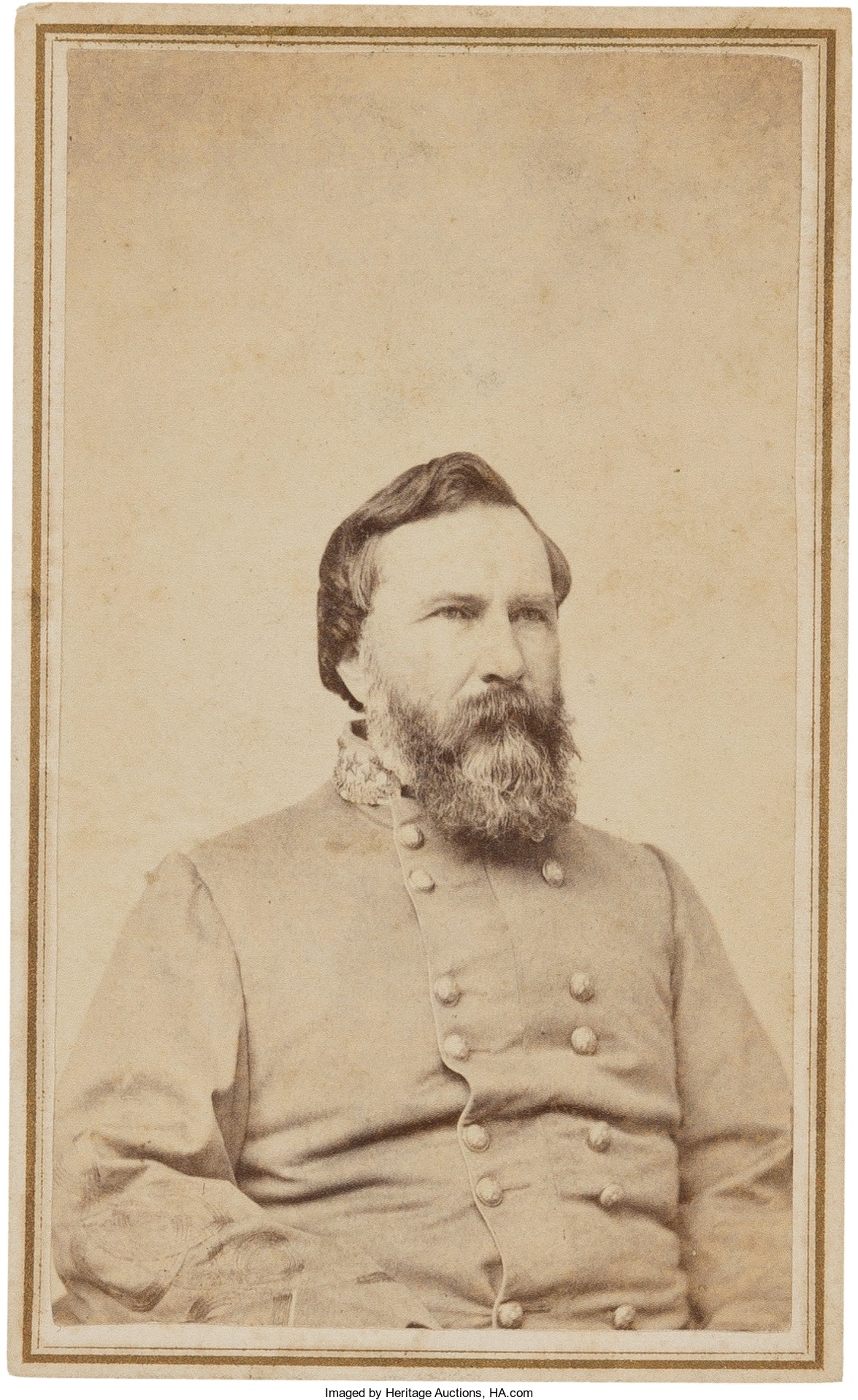

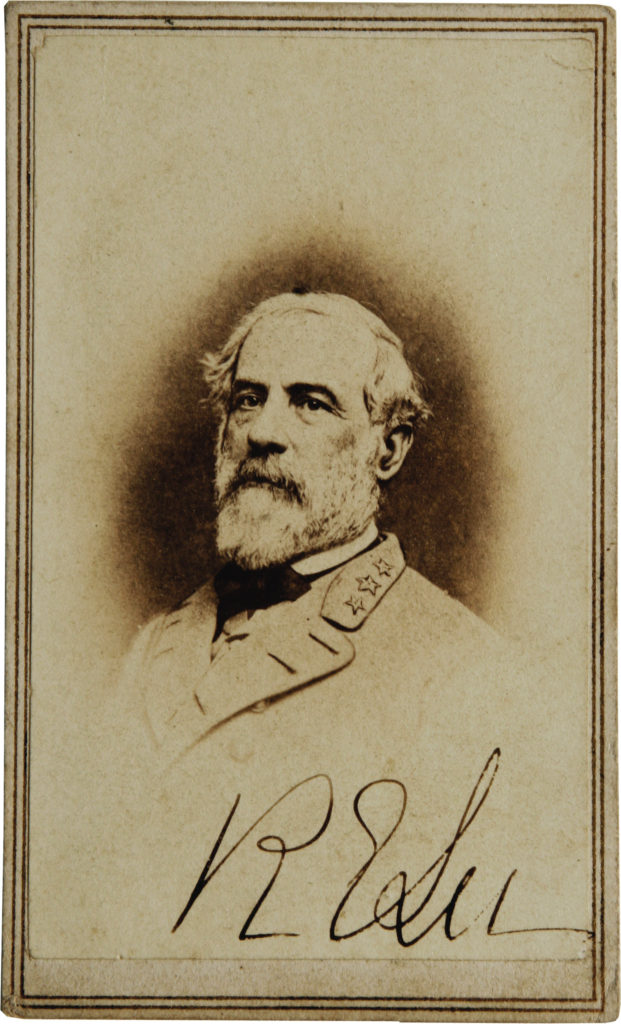

Of these, William Cuthbert Faulkner (1897-1962) didn’t give a damn about self-promotion. In fact, you could spell his name with or without the u. “Either way suits me,” he said quite often. As a boy, his parents took him to meet the great Confederate general (and Robert E. Lee’s right arm) James Longstreet (1821-1904). Little William had the temerity to ask, “What was the matter with you at Gettysburg? You should have won!” By reputation, Faulkner had a prickly side his whole life, but it didn’t seem to affect the quality of his writing.

When asked about grants for writers, Faulkner replied, “I’ve never known anything good in writing to come from having accepted any free gift of money. The good writers never apply to a foundation. They’re too busy writing something.” Faulkner would have been unaware that Foote (himself born in Greenville, Miss.) accepted Guggenheim Fellowships (1955-57) and Ford Foundation grants to get him through the 20 years of writing his Civil War narrative. However, as much as Faulkner’s work was admired by other writers, by 1945, all of his books, except for two, were out of print.

Yet just four years later, the unusually myopic Nobel Prize Committee made an unusually clear-sighted decision. In 1949, they awarded Faulkner the Nobel Prize for Literature, for which he became the only Mississippi-born Nobel winner. Two of his other works, A Fable (1954), and his last novel The Reivers (1962) won the Pulitzer for Fiction. Only two others have won the Pulitzer twice: Booth Tarkington 1919/1922 and John Updike 1982/1991.

Ernest Hemingway actually won in both 1941 and 1953, but the president of Columbia University, Nicholas Murray Butler, found Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls too offensive and convinced the committee to revere their decision and no prize was awarded in 1941. However, the movie version was nominated for nine Academy Awards and is a good piece of film.

In June 1943, Faulkner found an unopened letter that had been there for three months, since he didn’t recognize the return address. It was a proposal from writer and literary critic Malcolm Cowley to publish a “Portable Faulkner” to keep him from falling into literary obscurity. Faulkner was working as a Hollywood screenwriter (The Big Sleep) and was in danger of seeing all his books out of print. It was this effort that resuscitated Faulkner’s career and led directly to the 1949 Nobel Prize. Novelist and literary critic Robert Penn Warren called it the “great watershed moment,” for it saved Faulkner’s reputation and career.

True to style, when Cowley asked Faulkner to get Hemingway to write a preface, he refused. “It would be like asking one racehorse in the middle of the race to broadcast a blurb on another horse running in the same race.” He remained a prickly man to the end and I suspect it and all his wonderful writing came out of the same Southern Bourbon bottle.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].