By Jim O’Neal

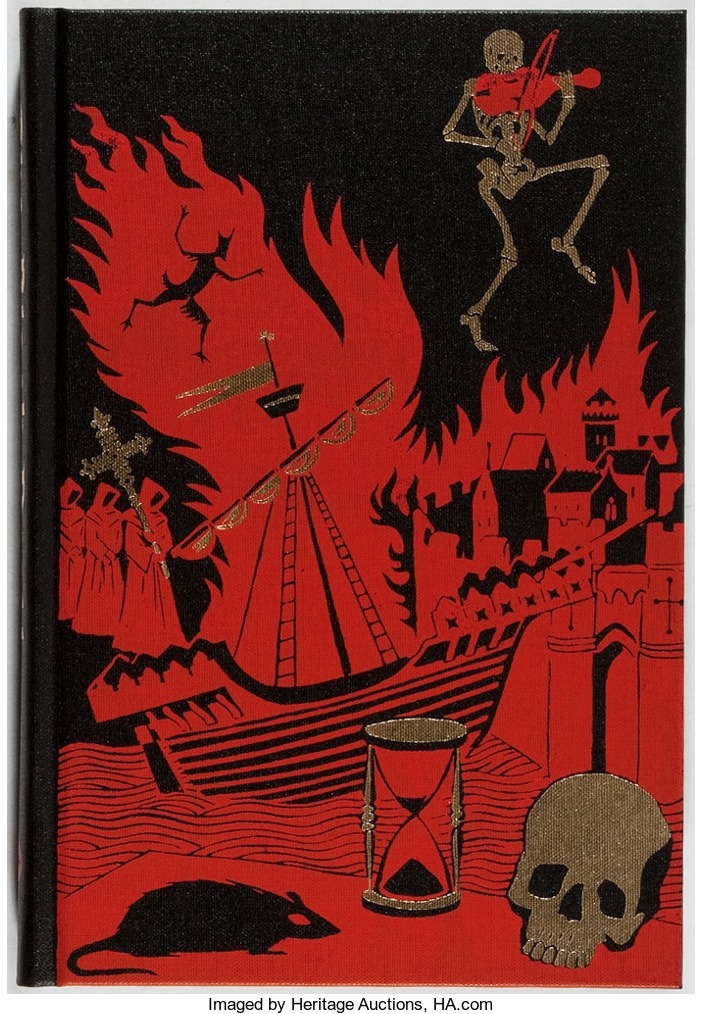

In five short years beginning in 1347, one-third of Europe – 25 million people – died of the bubonic plague. Many villages and towns lost 80 percent of their populations. A world that had just emerged from the Dark Ages and was moving into a new era was, suddenly, pockmarked with deserted farms, collapsed churches and zombie-like survivors.

Bubonic plague changed world history and mankind in ways that linger to this day. All subsequent epidemics – small pox, cholera, influenza and AIDS – are grim reminders of the terror of the “Black Death” and the specter of a world strewn with bodies and people defenseless against an invisible killer.

Although it wasn’t known at the time, the cause was a rat flea, Xenopsylla cheopis (X. cheopis), a ravenous creature that lived on black rats and other rodents. X. cheopis carried the virulent plague bacillus and it came in two forms, both deadly to humans.

One was from direct contact via a flea bite, which was followed by a black purple bruising and a mortality rate of 60 percent in as little as five to seven days. The predominant form was pneumonic, which spread from person to person by air, infecting the lungs, with death in two to three days.

It had started deep in Asia, where China was in a war with the Mongols that devastated great swaths of the countryside. Infected rats, no longer able to find food in the forests, headed to populated areas, where the disease spread rapidly.

By the 1330s, China had lost 35 million people out of 125 million. Then X. cheopis began to travel with traders across Mongolia and Central Asia. In 1345, the plague hit the lower Volga River, followed by the Caucasus and Crimea before finally arriving in Italy in the summer of 1347.

The disease arrived in London in November and killed one-third to half of the total population within three days. The population of England and Wales was 6 million people.

After a quiet winter, it sprung up again in 1349, burning through England to Scotland, leaping to Ireland and crossing the sea to Scandinavia. After devastating Moscow in 1852, it exhausted itself on the barren/empty Russian Steppes.

The plague returned in 1362 in numerous, smaller recurrences until the 1600s. Another wave of plague swept through Asia in the 19th century and it was then that the role of both X. cheopis and the Y. pestis bacteria was discovered.

Although the last plague pandemic was contained, hundreds of plague cases are reported each year since X. cheopis still exists in remote wild rodents, perhaps with yet another strategy to plague us. Despite the advent of curative antibiotics, Black Death is still lurking … somewhere.

Do you know what’s in your attic?

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].