By Jim O’Neal

During the heated debates between our Founding Fathers while formulating the Constitution and Bill of Rights, many invoked the principles of the Magna Carta to bolster their arguments. For almost 600 years, the Great Charter had stood as a beacon whenever men discussed their inherent rights.

The truth is somewhat more complicated.

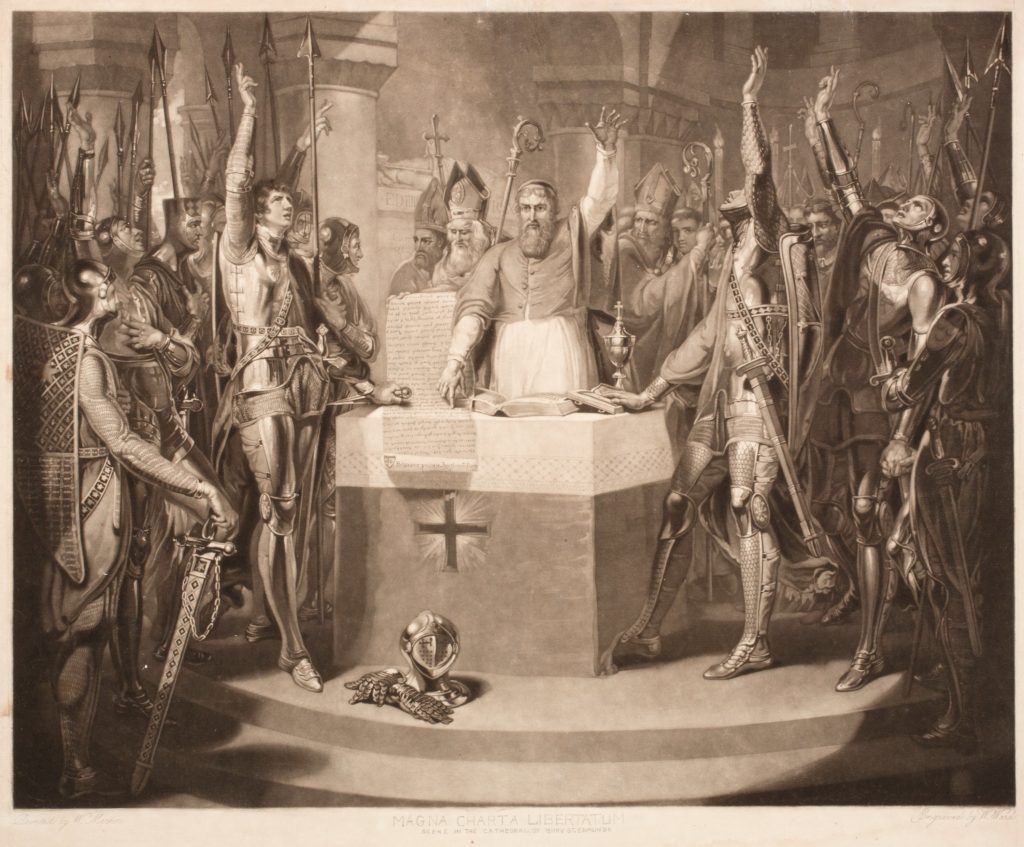

On June 15, 1215, King John of England signed a charter at Runnymede, a meadow beside the Thames River near Windsor fortress. The Archbishop of Canterbury had proposed the charter as a means to make peace between the king and a group of rebel barons. The document – which eventually became the Magna Carta – promised access to swift justice, no illegal imprisonment and limitations on feudal payments.

When John was enthroned as king in 1199, England was a feudal society, a land-based hierarchy where the king owned all the land. The tenants-in-chief (i.e. barons) received land from the king in exchange for loyalty and military service. They, in turn, leased the land to their own retainers, who leased to peasants. However, English monarchs had been levying ever-increasing higher taxes and financial burdens on the barons.

Starting with Henry I (1100-1135), the Crown established a series of Royal Courts that also raised revenue through fines and taxes. Discontent intensified under King John, who had lost a series of expensive campaigns against the French from 1200-1204 and had also lost the land in Normandy, which put the squeeze on the entire system. In addition to being inept at war, King John broke his commitments to the barons and both sides then disavowed any promises made.

One significant irony was that the Magna Carta originally only included the king and the barons. Ordinary citizens were totally ignored.

A new Magna Carta was issued in 1216 by Henry III and revised again in 1226 to raise taxes once again. Finally, in 1297, Edward I agreed to rights that evolved into English statute law, with a broad array of rights granted to all citizens.

The Magna Carta has acquired almost mythical status as the constitutional bedrock of citizen rights. It contributed to the development of parliament from the 13th century and was used by 17th century rebels to argue against the divine right of kings. Several American colonies’ charters contained clauses modeled on it, while the design of the Massachusetts seal chosen at the start of the Revolutionary War depicts a militiaman with sword in one hand and the Magna Carta in the other.

Americans believed the Crown had breached the fundamental law enjoyed by all English citizens, which led to the U.S. Constitution enacted in 1789 and the Bill of Rights adopted two years later. We are fortunate to live in a country governed by the rule of law and limitations on the arbitrary power of a government against its citizens.

Much blood has been spilled by many in defense of these beliefs.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is President and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as Chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].