By Jim O’Neal

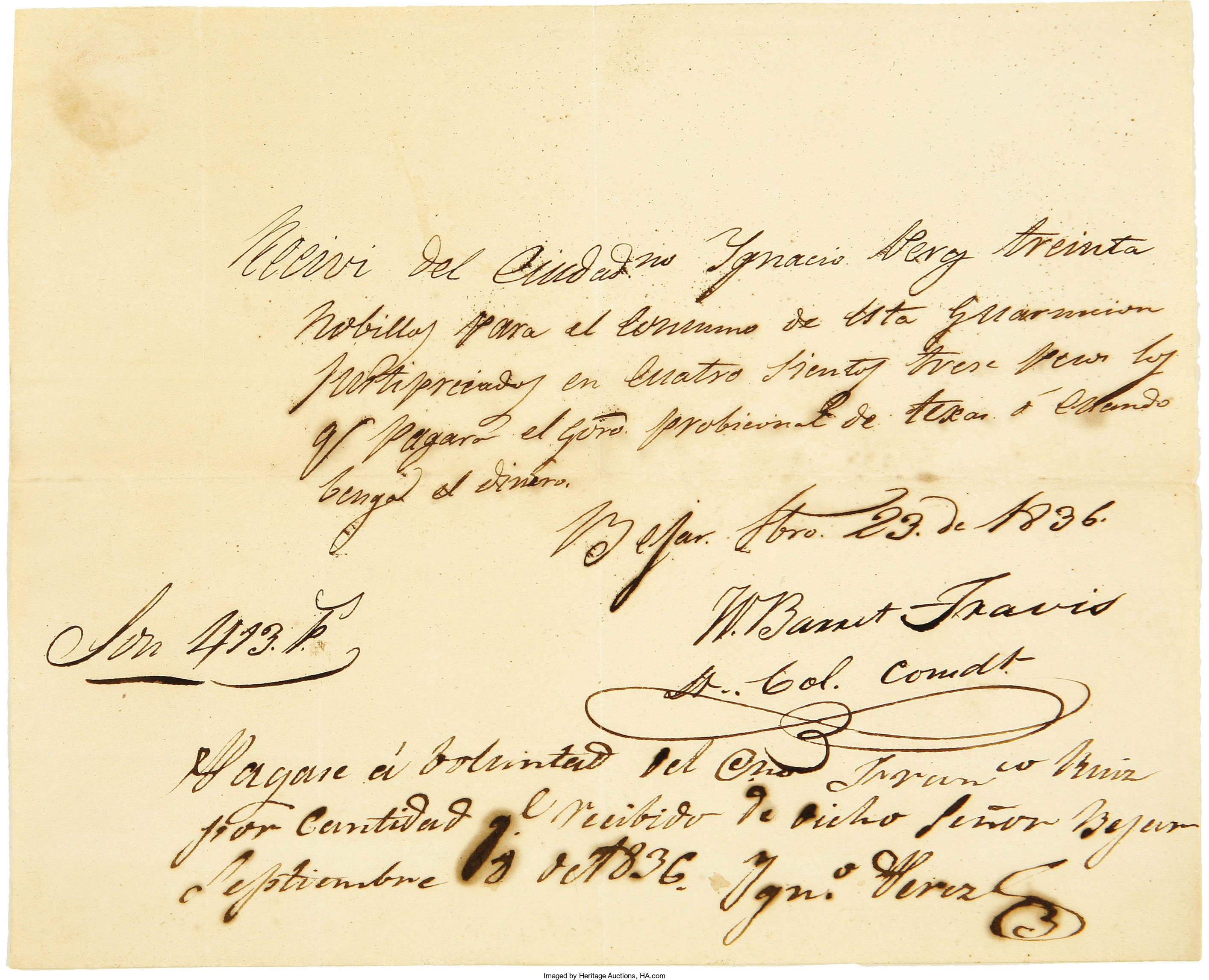

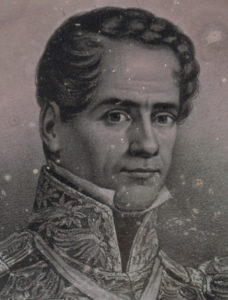

Early on March 6, 1836, the noise of assembling an infantry and the clamor of a cavalry preparing for battle sliced through the darkness as clouds covered the moonlight. Their assault targets were the adobe walls of a 118-year-old mission founded by Roman Catholic missionaries. Inside were no more than 200 armed men commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William Barret Travis, including David Crockett and Jim Bowie. (March 6 was James Bowie’s 40th birthday and before he gained fame for the knife.) For 12 days, this small group (called Texicans) had been successful in slowing Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna and his 3,000 troops.

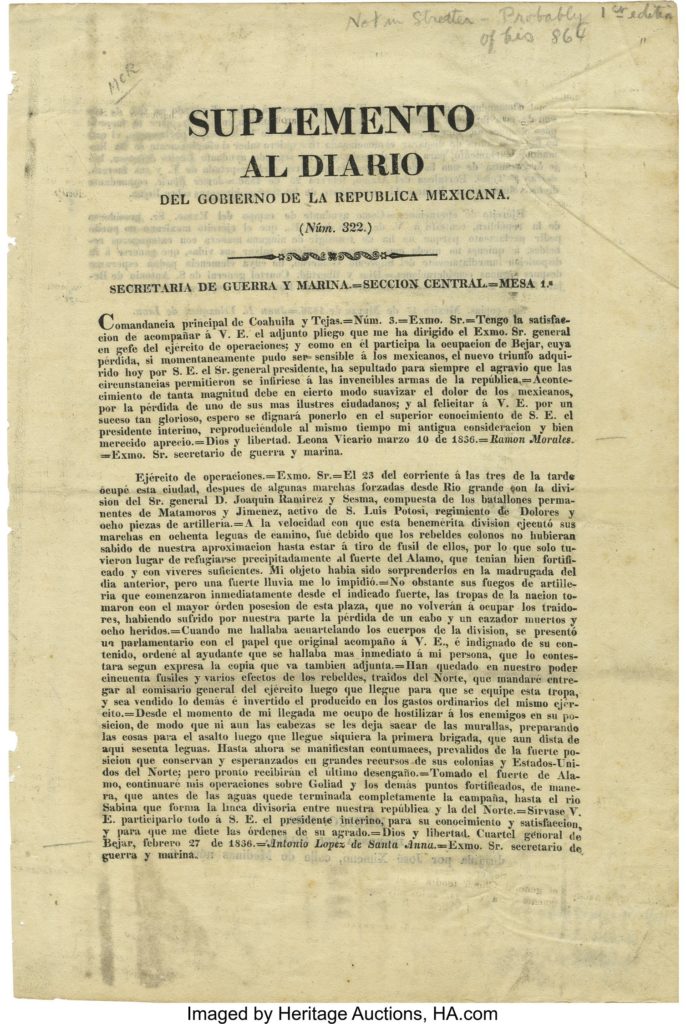

Finally, the Mexican troops were ready and raised the bloody red and white flag that signified that no quarter would be allowed. Then Mexican bugles blared the notes of the chilling “Degüello” and four groups were stationed around the Alamo to ensure that no one escaped alive. Their first assault was repulsed as was the second attempt. Then the attacking troops reformed and breached the walls. Within a matter of minutes, no Texicans were left alive. One popular legend survives that claims the wife of a lieutenant – Susan Dickerson and an infant daughter – were spared. President Santa Anna saluted her as she fled to safety.

According to international law, the Mexican military was well within their sovereign rights. The Alamo, and for that matter 100 percent of Texas, was legally Mexican territory. That included thousands of other Americans scattered from the Brazos to the Sabine River, who were challenging the legal authority of the official government.

For the previous 300 years, Spain had occupied Mexico as a colony known as Nueva España (New Spain). Much of this colonial area consisted of remnants of the remarkable Aztec Empire. In 1493, Pope Alexander VI (1492-1503) had issued Papal bulls that effectively granted Spain the exclusive right to explore the seas and claim all New World lands discovered by Columbus in his trips to the areas near North America. In return, Spain agreed to spread Christianity and the Catholic Church.

When the Mexicans initiated a war of independence, it was further complicated by European politics, Napoleon’s ambitions and aspirations from France. However, Mexico was fully committed to freedom and finally achieved their freedom from Spain. It was the first of several colonies whose independence was recognized by Spain. Ecuador was the second colony after Mexico to gain freedom. But the capture of the Alamo was not the beginning of peace. Less than two months later on April 21, 1836, Sam Houston and 800 Texans defeated Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto and the birth of the Republic of Texas was established.

Texas was annexed by the United States on Dec. 29, 1845, and admitted to the Union as the 28th state the same day. This was the action that precipitated the Mexican-American War (1846-1848).

Meanwhile, U.S. politics evolved into a rough, highly partisan affair as the country expanded west. Andrew Jackson served two terms as president and was followed by Vice President Martin Van Buren in 1836. However, the Panic of 1837, a financial crisis, soon engulfed the entire country. It ignited a major depression with profits, prices and wages all in a steep decline. An increase in unemployment created a national malaise and when banks raised interest rates, it extended the duration of the economic duress.

The country naturally blamed Van Buren and in 1840 turned to a military man to provide the leadership they hungered for. They picked General William Henry Harrison on a slogan of “Tippecanoe and Tyler too.” When Harrison died 30 days later, Vice President John Tyler quickly assumed the full powers of the presidency since there were no precise legal rules regarding succession and he thwarted any suggestions that he was only a temporary president pending another election. Tyler was the first vice president to succeed to the presidency without an election.

However, President Tyler soon lost the support of Congress when he attempted to assume legislative powers. He suffered the embarrassment of being the first president to have legislation overturned by Congressional veto. In 1844, Van Buren made a second try to win back the presidency and failed. Then the momentum shifted to younger upstarts like Henry Clay and James K. Polk, who had been elected to the House of Representatives seven times and would become the first and only Speaker of the House to become president.

Polk had long been considered Andy Jackson’s favorite since they had been born 20 miles apart in the Carolinas frontier. Polk had definitely been born in North Carolina, however, when Jackson was born 28 years earlier, there was no formal line between North and South Carolina. Jackson’s mother was never positive about exactly where her son had been born. Jackson just claimed it was North Carolina and no one ever had the nerve to challenge him (over anything) since they would be standing 10 steps away with a gun in their hand.

President Polk boldly proclaimed the policy of the United States was to be continental expansion. He welcomed Texas into the Union, bluffed the British out of one-half of Oregon and went to war with Mexico to grab California (and the gold) and a big chunk of the Southwest. He had announced his intention to serve only one term even before the election. As a formal lame duck, he was willing to spend his political capital freely and he expanded the powers of the presidency more than anyone before the Civil War. Although labeled a “dark horse” president, it’s hard to match it with his record. He chose to ride boldly across the bright new land and opened up the American West to a century of unbridled expansion.

A man of his word, he served just a single term in office. He had only been 49 at his inauguration – the youngest president up till then – and died a short 103 days after leaving office. His mother Jane was the first presidential mother to survive her son in life.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].