By Jim O’Neal

Thirteen-year-old Jefferson Davis was tired of school. He returned home from Wilkinson Academy, a few miles from the family cotton plantation, put his books on a table, and told his father he would not return. Samuel Davis shrugged and told his youngest son that he would now have to work with his hands rather than his brain. At dawn the next day, he gave young Jeff a large, thin cloth bag, took him to the cotton field and put him in a long line with the family slaves picking cotton.

Three days later, he was back at Wilkinson, happily reading and taking notes with his bandaged hands.

By 16, Jefferson had mastered Latin and Greek, was well read in history and literature, and eager to study law at the University of Virginia. Instead, he spent four years at West Point, graduated in the bottom third of his class and then entered the Army. He was 20 years old and fighting in both the Black Hawk War and the Mexican-American War.

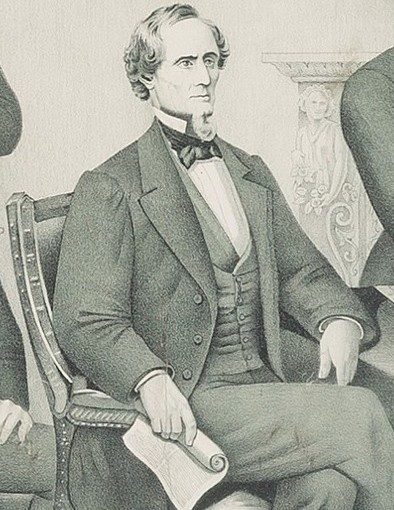

Jefferson Davis’ arrival in Washington, D.C., as a U.S. Senator from Mississippi was like a coronation. A true war hero at age 36, he was recognized by everyone and warmly greeted by all he met. After all, Jeff Davis was the first genuine war hero in the Senate in its entire 58 years!

His rise to prominence occurred as one generation of leaders died or retired – Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, John Quincy Adams, Daniel Webster – and a younger one was set to take over, led by Stephen Douglas (39), Andrew Johnson (39), Alexander Stephens (35), Salmon P. Chase (39) and William Seward (35).

Jeff Davis began to give important speeches in the Senate and everyone sensed he had a future in politics.

The Senate proved comfortable and prestigious, providing an intimate venue to discuss and debate the great issues of the time. Yet despite all the exciting opportunities facing the young nation, the hard fact was that slavery was a pernicious issue lurking in the shadows. It was like a cancer that seemed to grow more lethal after every “compromise” designed to resolve it.

An example was the fateful Compromise of 1850, intended to resolve the four-year controversy over the status of the new territories that accrued to the U.S. after the war with Mexico. California was admitted as a free state, and Texas had slaves, but had to surrender its claim to New Mexico. Utah and New Mexico were granted popular sovereignty (self-determination) and there was a more stringent Fugitive Slave Law (destined to be revoked by the Dred Scott reversal).

Jeff Davis felt so strongly that slavery was a 200-year tradition (to be decided by individual states) and detested the 1850 Compromise so much that he resigned his Senate seat to run for governor of Mississippi, confident this would enhance his national visibility, send a strong message to the North and bolster any wavering Southerners. The strategy failed when he lost the election, leaving him with no political office.

Davis bounced back into the Senate by one vote and new President Franklin Pierce (1852) selected him to be Secretary of War, a powerful position to resist the continuous threat from the North to impose their will on the South by any means necessary. The 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act just roiled the opposing forces and thoughts of secession were like dry kindling waiting for the proverbial spark. First was President James Buchanan (1856), a Democrat who seemed helpless or resigned to the inevitability of war.

As abolition forces gained momentum and the South grew even more resolute that they would not concede a principle that states’ rights trumped Federal aggression, it was only a question of how or what set of events would tip the nation into a civil war. The answer was in plain sight.

In the critical election year of 1860, though still hopeful of a peaceful settlement on slavery, Davis told an audience that if Republicans won the White House, the Union would have to be dissolved. “I love and venerate the Union of these states,” he said, “but I love liberty and Mississippi more.” When asked if Mississippi should secede if another state did, he roared, “I answer yes!” And if the U.S. Army tried to suppress it? Davis answered even more vehemently. “I will meet force with force!”

Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860.

The slavery issue was simply not resolvable by anything but force. Few foresaw how much force would be needed and the enormous carnage and loss of life involved. War always seems to be much more than anticipated. The 20th century would really amp it up and the 21st century has gotten off to a rocky start, as well.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].