By Jim O’Neal

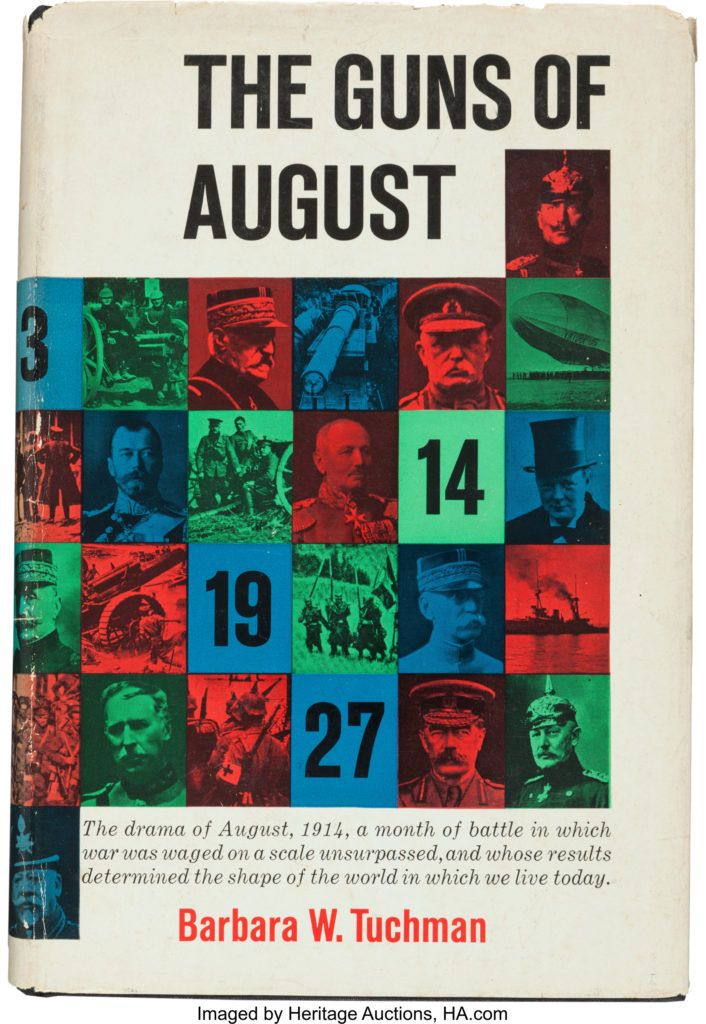

Simply mention the name of Barbara Tuchman and it brings back fond memories of her wonderful book The Guns of August, which won the Pulitzer in 1963. It brilliantly explains the complicated political intrigue that started innocuously in the summer of 1914 and then erupted into the horrors of the First World War. It is always a good reminder of how easily our foreign entanglements can innocently provoke another, except survivors today would call it the Last World War.

Tuchman (1912-89) won a second Pulitzer for her biography of General “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell and his travails in China-Burma-India during World War II. He was faced with trying to manage/control aviator Claire “Old Leatherface” Chennault and his famous Flying Tigers. He also had to contend with Chiang Kai-shek, who eventually became the first president of the Republic of China (1950-75). This dynamic duo conspired to have General Stilwell removed and were finally successful by badgering a tired and sick FDR.

However, it was a totally different award-winning book Tuchman published in 1978 that was much more provocative and controversial (at least to me). In A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century, she writes, “Of all the characteristics in which the medieval age differs from the modern, none is so striking as the comparative absence of interest in children.” She concluded, chillingly, that “a child was born and died and another took its place.”

Tuchman asserted that investing love in young children was so risky, so unrewarding, that everywhere it was seen as a pointless waste of energy. I politely refuse to accept that our ancestors were ever so jaded and callous. Surely, there was at least a twinge of sorrow, guilt or emotion.

Yet earlier, French author Philippe Ariès in his Centuries of Childhood made a remarkable claim that until the Victorian Age “the concept of childhood did not exist.” There is no doubt that children once died in great numbers. One-third died in their first year and 50 percent before their 5th birthday. Life was full of perils from the moment of conception and the most dangerous milestone was birth itself, when both child and mother were at risk due to a veritable catalog of dangerous practices and harmful substances.

And it was not just happening to poor or needy families. As Stephen Inwood notes in A History of London, death was a visitor in the best of homes and cities. English historian Edward Gibbon (The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire) lost all six of his siblings while growing up in the 1700s in Putney, a rich, healthy suburb of London. In his autobiography, Gibbon describes his childhood as “a puny child, neglected by my mother, starved by my nurse.” So death was apparently totally indifferent in choosing between rich and poor; but that is a far cry from not having a childhood per se.

To extend this into a situation where mothers became totally indifferent to young children because of high rates on infant mortality and thus it made little sense to invest emotionally in infants defies logic. Obviously, parents adjusted and had many children in order to guarantee that a few would survive … just as a sea turtle lays 1,000 eggs to have a few survive. To do otherwise is to invite extinction.

The world these respected people write so persuasively about would have been a sad, almost morbid place, with a landscape of tiny coffins. I say where is the proof?

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].