By Jim O’Neal

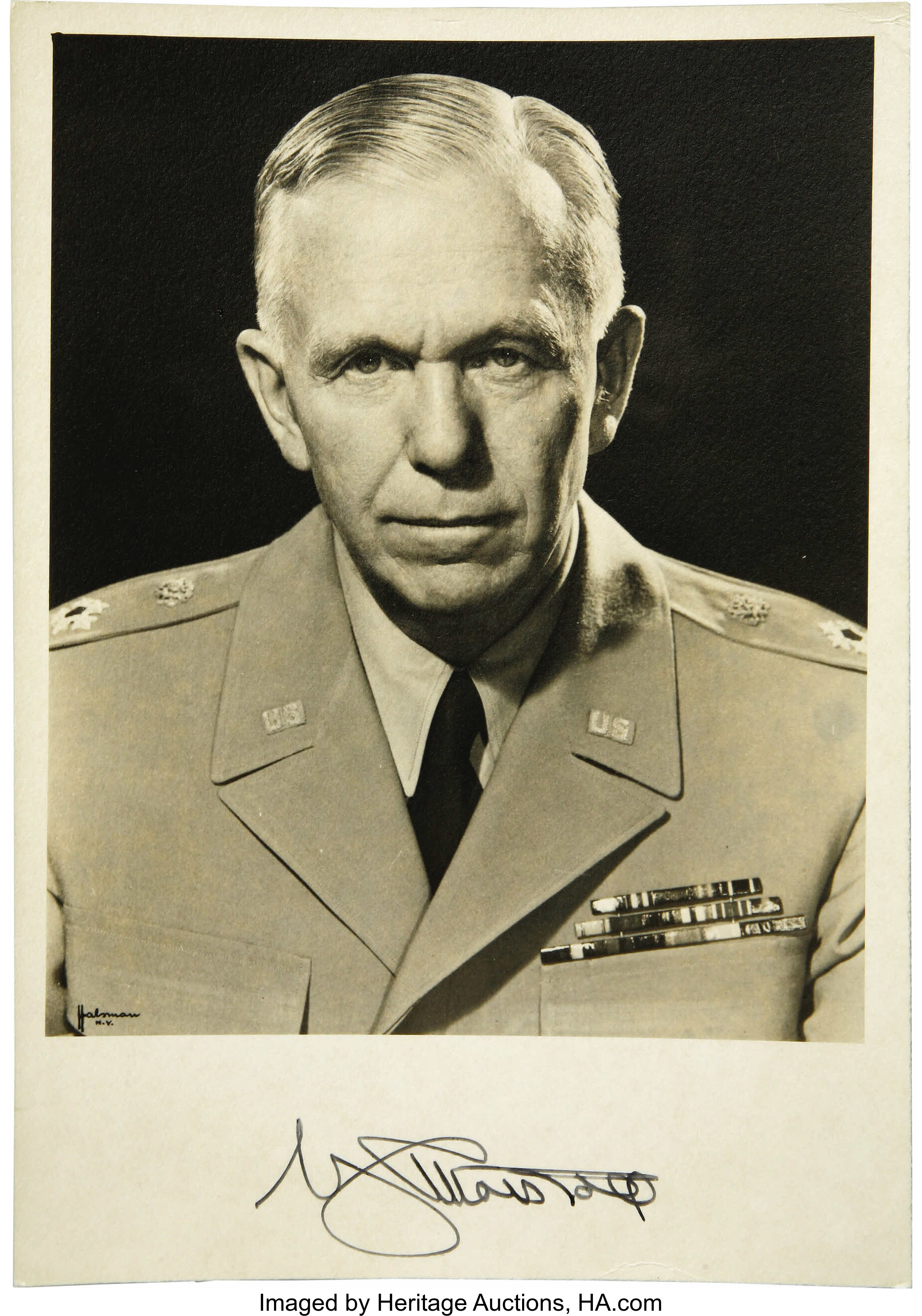

In Harvard Yard, a venue carefully chosen as dignified and non-controversial, Secretary of State George C. Marshall’s 15-minute speech on June 5, 1947, painted a grim picture for the graduates. With words crafted and refined by the most brilliant minds in the State Department, Marshall outlined the “continuing hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos” in a Europe still devastated after the end of World War II.

Marshall, one of the greatest Secretaries of State the United States has ever produced, asserted unequivocally that it was time for a comprehensive recovery plan. The only caveat was that “the initiation must come from Europe.” His words were much more than typical boilerplate commencement rhetoric and Great Britain’s wily Foreign Minister Ernest Bevin heard the message loud and clear. By July 3, he and his French counterpart, Georges Bidault, had invited 22 nations to Paris to develop a European Recovery Program (ERP). Bevin had been alerted to the importance by Dean Acheson, Marshall’s Under Secretary of State. Acheson was point man for the old Eastern establishment and had already done a masterful job of laying the groundwork for Marshall’s speech. He made the public aware that European cities still looked like bombs had just started falling, ports were still blocked, and farmers were hoarding crops because they couldn’t get a decent price. Furthur, Communist parties of France and Italy (upon direct orders from the Kremlin) had launched waves of strikes, destabilizing already shaky governments.

President Harry S. Truman was adamant that any assistance plan be called the Marshall Plan, honoring the man he believed to be the “greatest living American.” Yet much of Congress still viewed it as “Operation Rat Hole,” pouring money into an untrustworthy socialist blueprint.

The Soviets and their Eastern European satellites refused an invitation to participate and in February 1948, Joseph Stalin’s vicious coup in Prague crumpled Czechoslovakia’s coalition, which inspired speedy passage of the ERP. This dramatic action marked a significant step away from the FDR-era policy of non-commitment in European matters, especially expensive aid programs. The Truman administration had pragmatically accepted a stark fact – the United States was the only Western country with any money after WWII.

Shocked by reports of starvation in most of Europe and desperate to bolster friendly governments, the administration offered huge sums of money to any democratic country in Europe able to develop a plausible recovery scheme – even those in the Soviet sphere of influence – despite the near-maniacal resistance of the powerful and increasingly paranoid Stalin.

With no trepidation, on April 14, the freighter John H. Quick steamed out of Texas’ Galveston Harbor, bound for Bordeaux with 9,000 tons of American wheat. Soon, 150 ships were busy shuttling across the Atlantic carrying food, fuel, industrial equipment and construction materials – essential to rebuilding entire countries. The Marshall Plan’s most impressive achievement was its inherent magnanimity, for its very success returned Europe to a competitive position with the United States!

Winston Churchill wrote, “Many nations have arrived at the summit of the world, but none, before the United States, on this occasion, has chosen that moment of triumph, not for aggrandizement, but for further self-sacrifices.”

Truman may have been right about this greatest living American and his brief speech that altered a ravaged world and changed history for millions of people – who may have long forgotten the debt they owe him. Scholars are still studying the brilliant tactics involved.

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].

Intelligent Collector blogger JIM O’NEAL is an avid collector and history buff. He is president and CEO of Frito-Lay International [retired] and earlier served as chair and CEO of PepsiCo Restaurants International [KFC Pizza Hut and Taco Bell].